Off a broad, crowded pavement opposite the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation’s historical headquarters is the narrow gate into Azad Maidan flanked by rows of police vehicles and a line of Rapid Action Force personnel. This 25-acre open maidan, straddling between arterial roads in south Mumbai and bordered by the elite Bombay Gymkhana, is home to most protests in the city now – not the entire Maidan, only a small fraction on one side.

This ‘protest zone’ holds half a dozen shamianas or tents next to each other. Many have protesters sitting or lazing around, some groups sing protest songs on the mic and others hold little speeches for the motley crowd which gathers now and then. This hot June afternoon, the loudest voice comes from the shamiana of the sugarcane workers’ union demanding fair wages. The quieter one next to it has residents of Mariamma Nagar in Worli, overlooking the new Coastal Road, demanding justice to their housing woes.

Here since mid-May, they have been demanding redeveloped houses and temporary accommodation during the redevelopment. The authorities changed seven builders but work has not begun; instead, they were offered a pittance of Rs six lakh per household to leave the area and forego flats in the redeveloped buildings. They know how unfair it is given the sky-high property rates in Worli. They take turns to be at the protest, skipping meals and work. As a middle-aged man says, “What will we do with jobs if we don’t have homes?”

Their protest has fallen on deaf ears; no authority, not even a junior officer, has taken note. Their presence – the protest – does not bother any authority because it is almost invisible, does not disrupt the frenzied Mumbai’s life. The thousands who cross the Maidan on their way to work every day are disinterested. The loudest noise now is that of the underground metro station work occupying a larger area than the protesters. It’s easy to feel the futility of a protest here.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

No Maidan, no streets

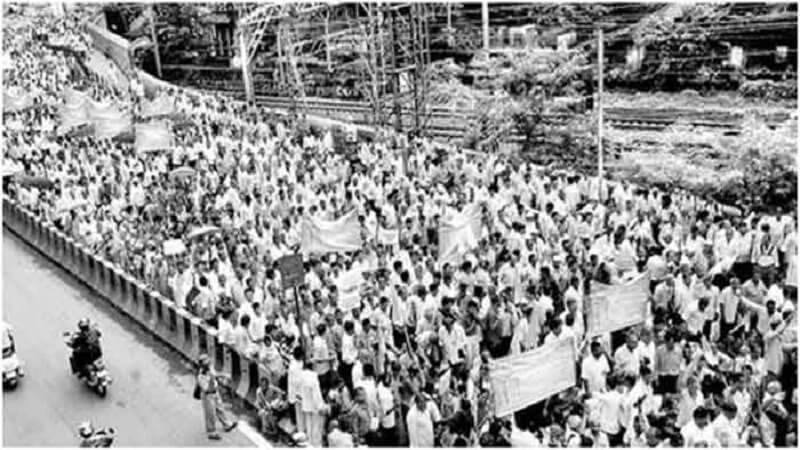

Azad Maidan was not always a listless protest space, say old-timers. Though a part of it was taken by cricket pitches – there are 20-22 now – the rest of the Maidan would throb with thousands or lakhs of protesters every few weeks, more often when the Maharashtra Assembly was in session a few kilometres away. Protesters gathered here and marched to the Assembly, or rallied here to raise such a loud voice that the government could not ignore. The roads and pavements around it would have protesters milling too, pamphlets and boards rested against the pavements.

Once a cattle-grazing land, then an open space abutting important buildings of the colonial era, Azad Maidan has witnessed some of the fiercest protests in Bombay which changed the course of politics and society. Two sepoys of the 1857 Revolt were executed here by the British, Mahatma Gandhi held one of his largest meetings in 1931, it has hosted some of India’s noted trade unionists. Muslims, Dalits, women, other genders, students and teachers, mill workers, housing rights and health activists, among other demonstrators, have all used this space during their struggles.

As the Maidan filled up, clarion calls reverberated across roads. Protesters tensed as police personnel drew their batons or weapons. Traffic in the area was disrupted for a few hours. The last notable protests here were against the Citizenship Amendment Act in December 2019 when nearly a lakh came but this turnout was an exception in recent years, and the thousands of farmers who came to Mumbai in 2018 during the Kisan Long March to flag the farm crisis they faced.

Just as the protest space at Azad Maidan has been shrunk, notable protest sites across south Mumbai are no longer available for collective action. The iconic Hutatma Chowk and Kala Ghoda were made out of bounds for protesters some years ago. Mantralaya, the government headquarters, was cordoned off for security reasons. The arterial streets from Churchgate and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus leading to Mantralaya, which carried millions of marchers over the last century, were closed for protests after citizens’ groups complained to courts and governments about disruption of traffic and noise.

“I remember the time when our protests used to go up to Mantralaya,” says Sonya Gill, general secretary, All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA). “How do you reach the government or get close to the seat of power otherwise,” she asks. Their morchas now happen at Dadar East; only a delegation goes to Mantralaya, if that. “Azad Maidan is too shut off. Protests have now moved away,” she says. Marching up to Mantralaya was the purpose of protests. Jatin Desai, journalist and veteran of many protests over 30 years, says, “In the background of the independence movement, governments allowed protests because it was a democratic right.”

Senior journalist and activist Gurbir Singh recounts the student movement during the Emergency in 1977 when protests would go all the way up to Kala Ghoda. “Protesters were blocked there, the police took a delegation to Mantralaya to meet the concerned minister, and the morcha dispersed after the delegation returned and reported the decisions. When the Assembly was in session, protesters were allowed only till Ritz Hotel near Churchgate station.” Kala Ghoda and Ritz Hotel area would see lakhs congregated, now only a few hundred come, points out Desai.

Photo: Twitter

Protesters thin out

In the post-liberalisation decades, as Mumbai’s manufacturing sector declined to give way to the burgeoning services sector and IT-based jobs, paring down the influence of trade unions and campaigners, workers’ struggles and collective action declined. The new sectors moved to contractual employment and informalisation of labour while actively discouraging the formations of unions.

This meant protests and demonstrations gradually faded away. Protests, the few that happened, were regulated in the small space at Azad Maidan or coalesced in central Mumbai as mill workers agitated for jobs and houses. Dadar, a hub of protests even earlier given its proximity to mills, saw demonstrations – on its eastern side, outside the station; on its western side, near Tilak Bridge.

The Bombay High Court’s 1997 order, on a petition by Mumbai’s citizens’ groups, did not help protesters. It made Azad Maidan the end point of morchas. Disruption of traffic and pedestrian movement was frowned upon which meant street demonstrations were replaced by sit-ins. Street protests had meant passers-by would be reached out to with issues. People rushing home from work would be nonchalant or accommodate protesters on ‘their’ streets. “If roads were jammed, people would get off public transport and walk. I don’t remember people complaining,” says Singh.

“This interaction between the public and protestors was the life-blood of these protests. They knew that the roads would be blocked and they would have to wait for some time on the road, but that is how democracy functions…The nature and cause of the protests underlined the choice of space,” points out Dr Mamta Mantri her book Cities and Protests: Perspectives in Spatial Criticism.[1]

However, despite the restriction of public spaces for protests, people have come out in large numbers when a cause deeply disturbed them. Shweta Damle, founder of Habitat and Livelihood Welfare Association, remembers the protests against evictions spearheaded by social activist Medha Patkar. “People made make-shift tenements at Azad Maidan which itself became a political statement,” says Damle. But even this was well over 15 years ago.

Newer spaces, smaller protests

Dadar station area continues to draw protesters though in smaller numbers. The agitations against the release of convicts in the Bilkis Bano gang rape case and against Unnao and Kathua rape cases, began outside Dadar station amidst the heavy traffic and commuter rush, occupied the Tilak Bridge and culminated at Kotwal Garden. Women protesters gathered on the pavement abutting Kotwal Garden in solidarity with the women farmers agitating on Delhi’s outskirts in 2021.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

In the radial area, near KEM Hospital, stands the Kamgar Maidan, literally Workers’ Maidan. With the streets leading to it transformed into enclaves, the Maidan dwarfed by the city’s ubiquitous towers on all sides, it is easy to miss its significance. Kamgar Maidan has a rich history of hosting protests and cultural programmes for mill workers; it is now rented out for weddings and celebratory functions.

“The name ‘Kamgar Maidan’ remains even though there are no mills or workers here anymore,” says Pravin Ghag, president of the Girni Kamgar Sangharsh Samiti. “Mill workers of nearly 60 mills spread across Worli, Dadar, Sewri and Byculla, known as Girangaon or village of mills, protested here for better working hours, bonus and wages as also outside mill gates.” The remaining few mill workers, he adds, were denied permission to hold a meeting here – an irony.

A few minutes’ walk from Kamgar Maidan, in Lalbaug, lies the historic Bharatmata Chowk, named after the famous single screen theatre. Once a protest destination, it is now dominated by the Lalbaug flyover turning the space below into a mere intersection. Jambori Maidan, in the erstwhile mill areas, used to be a favoured protest site too. Singh recalls students, besides mill workers, using these spaces for rasta roko agitations under the banner of the Naujawan Bharat Sabha.

As the mill areas gentrified with massive commercial or ultra-luxury residential towers, the many maidans here stand as mute witnesses of historic workers’ struggles, their contribution to Mumbai’s socio-political fabric forgotten. “Workers’ issues changed from labour-related to housing, so protests happened at Slum Redevelopment Authority or MMRDA,” explains Shweta Damle.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Changing city, shifting order

Shivaji Park, on the western side, too was a popular protest site but is now more closely identified with political meetings, especially of the Shiv Sena. Often, the maidans in the mills’ area and the Shivaji Park precinct would be the starting point for demonstrations culminating at protest spaces in south Mumbai.

From mill workers to slum dwellers and residents of other informal settlements whose right to housing was undermined, they joined protests spilling into the streets and “paralysing south Mumbai,” as Gurbir Singh describes it. Nivara Hakk Sangharsh Samiti, housing advocacy coalition which Singh co-founded, once took over the Asiatic Society of Mumbai and the Horniman Circle Garden to protest the eviction of slum dwellers of Sanjay Gandhi Nagar in Colaba.

The State felt accountable to protesters, says Jatin Desai. “Ministers used to visit protest sites. The Congress party’s ministers believed it was their responsibility to speak to demonstrators. Now, you are not sure if ministers will meet you, so many refrain from joining protests.”

Even mill workers – the few thousands left – do not get permission to protest anywhere except Azad Maidan but, here, the public is blissfully unaware of protests. Ghag laments that when protests go off the streets, they become invisible. “We protest because the common man needs to know that mill workers are still struggling… At Azad Maidan, no one outside even knows when a speech is being delivered. Restricting protests to Azad Maidan was a deliberate move by the State to quieten our movement,” he says. Sonya Gill calls for rejecting “this ghetto of Azad Maidan”.

Photo: Siddhesh Pisal

Women at the forefront

In August 1942, as the Quit India movement located itself at Gowalia Tank Maidan, near Chowpatty, women leaders like Aruna Asaf Ali led those gathered to hoist the Tricolour. Now named August Kranti Maidan, it saw a massive turnout in December 2019 against the CAA.

In Nagpada, an inner area of south Mumbai, women created Mumbai Bagh replicating Shaheen Bagh even as other protesters took to the streets in Dharavi, Chembur, and Malwani. The sit-in at Mumbai Bagh drew crowds. Journalist and researcher Sameera Khan says, “For the first time, young girls and women witnessed their mothers, grandmothers, aunts and neighbours sitting on the street when there were always restrictions on outdoor movement…This and Shaheen Bagh protests were unusual because women do not lay claim to public space.” Khan says other activists trooped in to educate the women about their rights beyond the CAA-NRC.

The city’s women articulating issues of the day was not new. Back in 1972, Mahangai Pratikar Samyukta Mahila Samiti, a coalition of women from varied political groups, formed the anti-price rise movement. Thousands of women led by socialist Mrinal Gore and communist Ahilya Rangnekar carried out latne morcha (rolling pin protest). Mass involvement of women has declined in recent years as working classes have been pushed outside city limits. “Women have to travel from far off suburbs to protest. It’s costly, time-consuming and arduous,” explains Gill.

The digital era has transformed the art of protesting – Gurbir Singh says hardly anyone goes on a hunger strike now – and online activism plays a large role in opinion building. Damle believes that it is important for people to join forces to save the few protest spaces that are still left: “Unless the middle class wakes up to the consumerist and predatory nature of their aspirations, we cannot build healthy cities for all.”

Author Leslie Kern writes in her book Feminist City that any vision of a feminist city must consider the role of activism. The marginalised are rarely ever “given” freedom or rights without a struggle. The need for protests is not over; protesters will be pushed to new locations and newer forms of protests, but public spaces increasingly restricted for protests does not bode well for the future.

Jashvitha Dhagey developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover photo: Azad Maidan/ Jashvitha Dhagey