As a child, I remember my Goa as a land of plenty and such pristine beauty that it was no wonder it was called a paradise on earth. Its green landscapes – the Western Ghats, plateaus full of wild flowers, rich agrarian lands, coconut-lined bunds, abundant rivers, and beaches with sand dunes made for postcard memories of my childhood. People were laid back in the villages, everything moved at a snail’s pace, and life was full of contentment. The cities were slow too – we walked or cycled to school, ate berries on the way, spent evenings wandering on hillocks and running across dry fields.

For the hippies, the first tourists, this idyllic life in Goa was a big draw. Most houses were ground-floor structures and it was only in the city of Panjim and towns like Vasco and Margao that it was possible to find two-storey or three- storey buildings. There were not too many cars. Most people travelled by buses, ferries, and the local train in South Goa. The beaches were relatively empty, village streets were idyllic, and markets the hubs for local gossip and news. Migrations were limited to Panjim, Margao, and Vasco as local people moved from villages for better education and jobs.

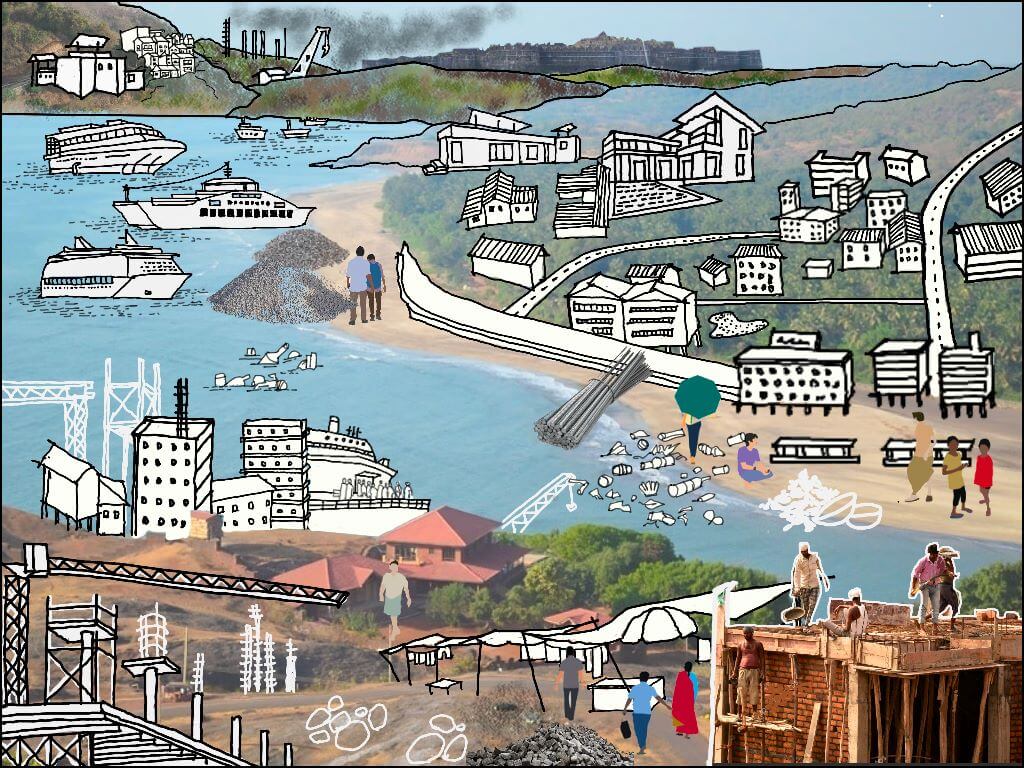

In the last few decades, the rapid urbanisation of cities[1] and towns in Goa has been visible but, now, its complete commodification and new colonisation is so blatant that we are seeing rivers being emptied of sand, hills cut brazenly, trees decimated in lands that used to be thickly forested. Worse are the gigantic developments by real estate developers coming up on virgin plateaus, towering apartment blocks replete on hill slopes, artificial beaches and ultra luxury villas each with a swimming pool.[2]

Across Goa’s lush green countryside are billboards that advertise such concrete-filled development projects and gambling in casinos. The serpentine highway cutting across Goa’s landscape, the double-tracking of the railway for coal transportation[3] are also infrastructure projects that further usurped agricultural and forest land[4] disregarding the irreplaceable green infrastructure of clean air from forests, river sources, flood management systems called the khazans – a unique coastal estuarine ecosystem – and coastal mangrove forests-our first line of defence against rise in sea level and tsunamis.

The land shift

Goa and small are synonymous. As urbanisation expanded, the land for construction shrank. The Covid-19 pandemic was a tipping point for many living in large metros across India to make the move to settle in Goa while a large number continued to invest in second and third homes in this paradise. Land, it seems, was affordable for them but had become out of reach for local Goans.[5] The locals became brokers, some even sold the small plots of land, and frauds became a way to lure innocent investors. Land scams reached a peak.[6] The final axe struck Goa hard with the controversial ‘land use change’ provision. In 2023, the Goa Town and Country Planning (TCP) department announced amendments to the TCP Act that allowed for the ‘correction’ of what it called ‘errors’ in the regional plans and land use maps. This was a euphemism because the intention was to convert green zones into settlement areas to enable construction on them. Goa’s authorities were signing away the future of the paradise.

These provisions were made possible by the controversial Sections 17-2 [7] (zone changes of individual plots) and 39A [8] (to alter the Regional Plan and Outline Development Plans for zone changes). These were reportedly introduced to facilitate the demand from big players who wanted to invest in Goa. And these were not small parcels of land but lakhs of square metres of land sliced cleverly for the concretisation table.[9]

These amendments rapidly accelerated land conversions. Large tracts of land in the guise of ‘corrections’ got reclassified without any public consultations. Within a year, from March 2023 to March 2024 two million square metres of land was converted from green to grey.[10] Eco-sensitive zones that included private forests, paddy fields, orchards and natural cover were all converted for development. Goans are deeply connected to their land and the natural environment. Sacred groves, khazan lands, kulaghars, plateaus, seemed to be under assault by the government through the amendments. This resulted in public outcry, silent protests, and demands to oust the chief town planner Rajesh Naik as well as TCP Minister Vishwajit Rane.[11] Both were accused of corruption and paving the way for large scale destruction of agricultural land[12] and eco-sensitive zones for massive real estate development.

Goans did not sit quiet

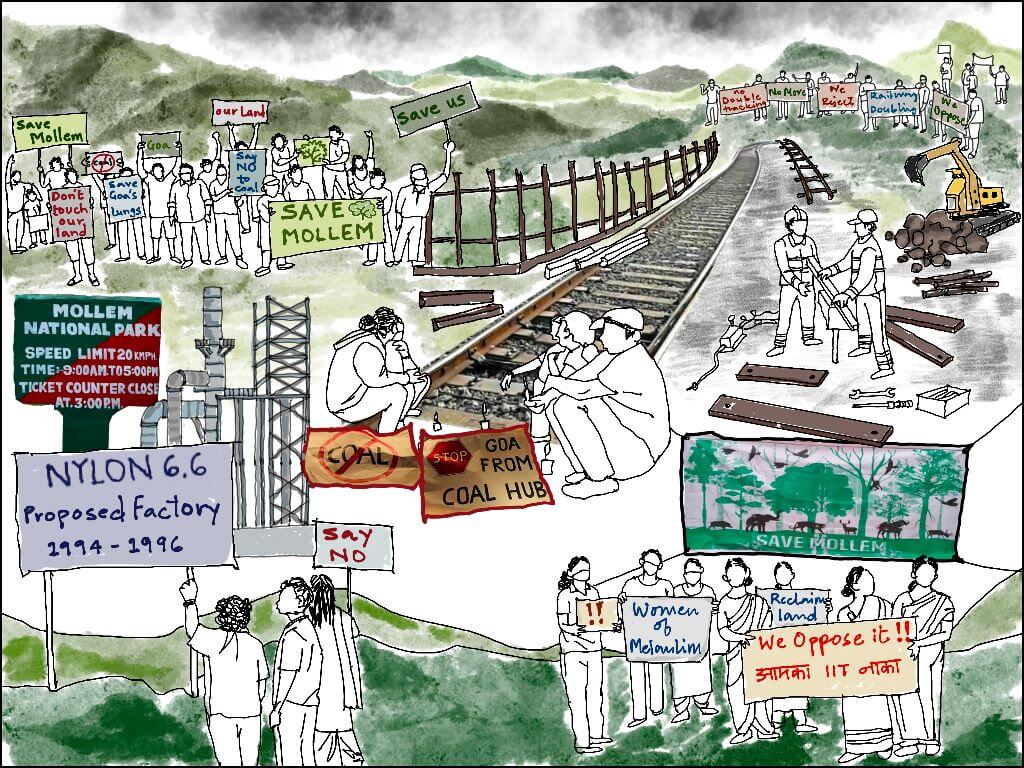

Movements to protect land are not new to Goa. There have been huge agitations in the past like the Nylon 66 protests[13] in the 1990s against the Thapar-Du Pont chemical plant because of environmental concerns. In the late 1990s there was another major environmental agitation against the Meta Strips company[14] that had plans to set up a scrap processing unit for exporting metal and disposing of toxic waste in Goa. The people’s movement succeeded in moving the High Court to stop its operation although the company was later engaged in land transfer controversies.

The opposition to the Konkan Railway alignment and new stations at Sarzora, Neura, and Mayem – all highly eco-sensitive areas – raged on for years in the early 1990s. Locals feared environmental destruction, loss of biodiversity and natural resources, potential coal transportation, increased migration and disruption of local communities. While changes happened in urbanisation and out-migration from areas on its alignment, a IIT-Bombay study last year showed that forest land had not substantially reduced but was replaced by plantation and agricultural lands had declined in large measure.[15]

A recent landmark people’s movements to protect Goa’s land and environment have been the examples by the women of Melaulim in Guleli village[16] (North Goa) in 2020, opposing the proposed IIT on 10 lakh square metres[17] of orchard land and parts of the biosphere of the Western Ghats. The institute was opposed by villagers of Loliem and Cortali in South Goa. Then, farmers in Taleigao[18] protested the land-filling and destruction of cultivable lands for a second Panchayat Ghar. And the recent ‘Save Mollem’ campaign[19] by the Amche Mollem group sought to raise awareness on three infrastructure projects – double-tracking of railways, highway expansion, and a power transmission line and electricity substation[20] – all proposed in the protected forests of Goa.

These projects threatened to fragment forests, destroy vast areas of rich biodiversity, endanger wildlife including tigers and Gaur, Goa’s state animal, and negatively impact endemic biodiversity besides impacting the local communities. The movement spearheaded by researchers, artists, local residents gained national and international support using social media, celebrity involvement, public demonstrations, online petitions, street protests, flash mobs, and even railway track night vigil at Chandor and Arrossim villages to demand revocation of wildlife and forest clearances.

Every village, a JCB

Eco-sensitive areas, No-Development zones, agricultural zones, Coastal Regulation Zone areas are all protected by environmental laws but the two controversial amendments – Sections 17-2 and 39A – to the TCP Act and the state policy to boost eco-tourism has meant more and more people as well as developers are purchasing large parcels of forest land and getting it converted under the guise of eco-tourism. The forests are critical for Goa’s sustainability and survival.

Goa is gone. The highways that serpentine across Goa’s green landscape have already destroyed key hill slopes, lush agrarian lands, mangroves and wetlands.[21] Goa’s plateaus and low-lying fields are under threat as mega projects and gated colonies are being built overnight in collusion with local bodies and departments like the TCP with the concerns of locals about land and green assets overridden. Almost every village has large portions of its pristine land barricaded with metal sheets, hiding massive JCBs and trucks laden with laterite soil that will be dumped somewhere far from the prying eyes of people. Hill slopes with deep mined pits are common with mining companies waiting to over-extract iron ore.

Despite the ban on stone quarrying and sand mining, laterite stone is still being extracted and sand mined[22] using pumps illegally at many places in Goa. Socially, the very character of Assagao, Moira, and Aldona villages has changed as old houses are bought and converted into boutiques and restaurants while new villas and luxury developments concretise these once unique heritage hamlets. The IIT fever did not cool down. Now, it is being proposed at Codar-Bethora with the[23] government ready to take over a whopping 14.63 lakh square metres of fertile land. It is partly under cultivation but the government claims it is unused and uncultivated. The villagers are opposing the project and, in fact, questioning the government about why there is not even a balwadi or nursery here yet.

The villagers of Chimbel Merces are currently opposing the Unity Mall[24] proposed to come up on land still under dispute for an IT Park. This land is part of the Kadamba plateau which has been under siege with massive constructions of gated colonies, commercial buildings, private schools, and hotels.[25] At its edges is the most pristine heritage Toyaar (Chimbel) lake that feeds the underground springs, replenishes the groundwater, and sustains agriculture in the village. The villagers opposed the IT Park and now are resolute in their opposition to the gigantic mall which they believe will destroy the lake and pollute groundwater.

The way ahead

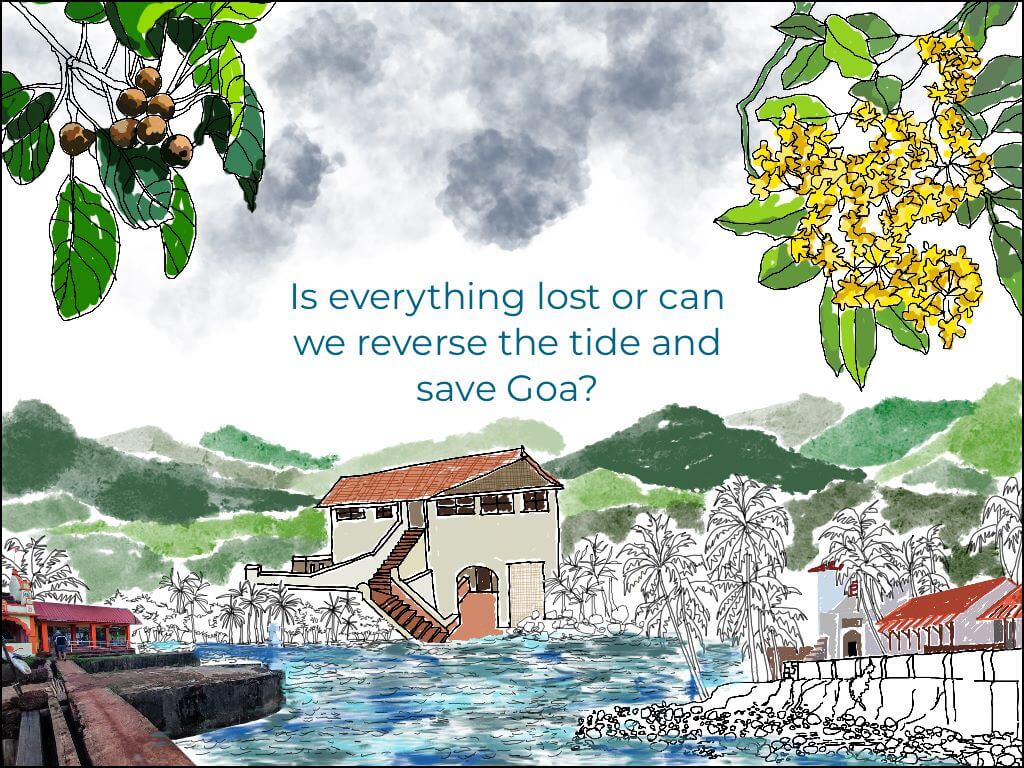

Is everything lost already or can we Goans reverse the tide and save Goa? Of course, we can. Firstly, it needs a conscious humanising of local representatives, government officers, and ministers from being power-hungry, money mongering and corrupt. They need reformation to heal, perhaps some education about ecology too, and the freedom to assert their constitutional authority to protect the rich ecological resources.

What Goa most needs is its government to commit to safeguarding the state from climate change and sea level rise. Instead, governments seem keen to tear down the existing ecology. What Goa also needs is to reverse the regressive amendments that allow land conversions of eco-sensitive lands and protected private forests. These require people’s movements but also sensitive or aware political class and bureaucrats.

The state must take cognizance of the massive loss of tree cover and habitat loss[26] and curb tree-cutting across the state, and penalise such acts by ensuring that offenders plant indigenous trees and help restore the green cover. Goa needs a policy to promote and revive mud building, natural building, and sustainable building – indigenous forms here that respected local ecology. Our land, rivers and biodiversity in environment are our assets, our lifelines, a mother that sustains us.

Tallulah D’Silva is the founder and principal architect of ‘architecture t’ based in Goa. She is passionate about architecture, sustainability, vernacular building systems, ecology and Goa. Social and environmental issues are close to her heart. She loves design and build, cost effective construction, entrepreneurship, citizen initiatives, social architecture, writing, mentoring, environment, outdoor learning art, installations and is an excellent net-worker and doer. She balances her passion for architecture, environment, community, alternative learning and engaging with children and youth.

Illustrations: Nigel DeSouza and Nikeita Saraf