A fortnight after 40-year-old Krishna Ghuge, a domestic worker from Nandurbar, travelled 419 kilometres to Mumbai for her 15-year-old son’s treatment at King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital in Parel, Mumbai, she was still awaiting a diagnosis. “He was operated on when he was only one-day-old but he frequently gets pneumonia,” she says.

The family consulted doctors in Surat and Ahmedabad till a doctor in Silvassa finally referred them to KEM. Here, they met doctors in five departments and got a bronchoscopy done but a diagnosis still eludes them. During the day, in the Mumbai heat or rain, Ghuge and her son occupy a bench in the hospital premises and, at night, sleep on the footpath like tens of others. Most of their identity documents, needed at hospitals, were chewed by rats back home making it more difficult to get a foothold in the hospitals.

At the Bai Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children, also in Parel, 37-year-old Sarita Gupta has travelled nearly 35 kilometres hoping for neonatal care for her 15-day-old baby. The infant recovers in the NICU as she spends anxious moments outside. Like these women, hundreds flock to Mumbai’s public hospitals to seek life-saving treatments and quality medical attention at affordable cost. Hospitals like KEM, Bai Jerbai Wadia Hospital for Children, Topiwala National Medical College & BYL Nair Charitable Hospital, and Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital, popularly known as Sion Hospital, and the state government’s Sir JJ Hospital are overwhelmed.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

These are mostly in south and central Mumbai. Its suburbs have fewer full-fledged ones though they have peripheral ones. Together, Mumbai’s public hospitals have nearly 17,190 beds (15,302 civic and 1,885 in JJ), according to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) but the catch is what is unsaid. The number of beds in private hospitals is around twice this number – nearly 31,000 – and expanding as many mid-size hospitals have applied to be 800-1,000-bed ones.

This, say healthcare professionals and advocacy organisations like the Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, is the worrying trend: Even as the dependence on public hospitals rises and they grapple with staff shortage, delayed procurements and so on, the private sector is on a rapid expansion spree. Moreover, the BMC announced plans to adopt the Public Private Partnership (PPP) model to reduce operational costs.[1]

This move is set to impact hospitals in Mumbai’s suburbs such as Dr Ambedkar Hospital in Kandivali, Rajawadi Hospital in Ghatkopar, Bhabha Hospital in Bandra and Kurla, MT Agarwal in Mulund, and Bhagwati in Borivali.[2] The newly-constructed Shatabdi Hospital in Govandi and the Super Speciality Hospital in Mankhurd – suburbs that are home to the poorest in Mumbai – are on course to be privatised. Further, in the PPP hospitals, the BMC recently declared that only yellow or orange ration cardholders of Mumbai/Mumbai Metropolitan Region would be provided subsidised services while those from outside will pay a different rate.[3]

Mumbai’s major public hospitals collectively have a patient load of 60 lakh OPD visits, 2.5 lakh admissions and 1.5 lakh surgeries every year, while the numbers for peripheral hospitals are 42 lakh OPD visits, 2.5 lakh admissions and 42,000 surgeries annually, according to official data. The writing on the wall is clear – Mumbai’s healthcare is moving towards the private sector but, for a large number of people in the city and outside it, public hospitals are the only succour that’s affordable and accessible.

Photo: Varun Shetty

The missing network

A city’s healthcare infrastructure must ensure sensitive care of patients, prompt response, and so on, but at the very least, it should be easily available and accessible to all. This is critical when people’s health is compromised by housing typologies, uninhabitable living conditions, lack of sanitation and open spaces. High rates of depression, anxiety and other mental illnesses are also linked with the way cities are built.[4]

The cornerstone in public healthcare is the neighbourhood clinic or the area’s hospital usually found at the second tier of the network that has large public hospitals at the apex. The neighbourhood clinics are sorely missing in Mumbai except during Covid-19 and the secondary hospitals are under-funded and ill-equipped. The lack of a robust secondary and neighbourhood infrastructure means increased load on the large public hospitals, unnecessary travel, and long wait time for all patients.

The redevelopment has already made healthcare a challenge for many.[5] The National Building Code (NBC) norms, incorporated in the city’s Development Plan 2034, recommend one dispensary for every 15,000 persons. Mumbai requires 858 dispensaries but has only 199, less than one-fourth, in 2021.[6]

As Dr Abhay Shukla, national co-convenor of JSA, points out, “If a child has pneumonia, an elderly person has urinary obstruction, a woman is in complicated labour, they should be dealt with in the secondary hospitals instead of going to Sion or KEM. The interminable wait at the larger hospitals often sends patients scurrying to the nearest private facility – but this comes at a cost.” For example, a CT Scan could be without charge or at nominal cost in public hospitals but cost upwards of Rs 10,000 at a private diagnostic centres.

With nearly 60 percent of Mumbai earning less than Rs 20,000 a month[7] and patients coming to the city for treatment not better off, healthcare is a question not of availability but sheer affordability. “Where more than 50 percent of people earn survival wages, privatisation of public health service is a crime. It creates profits for corporations, not inclusion,” says Shubham Kothari, member of Jan Haq Sangharsh Samiti, a part of the Aspatal Bachao Nijikaran Hatao Samiti.

The critical need for a robust multi-tier network was emphasised in a IIT-Bombay paper in 2021 titled ‘Public transit accessibility approach to understand the equity for public healthcare services: A case study of Greater Mumbai’. It found that nearly 35 percent of the city’s population resides in wards with high social vulnerability and low accessibility to hospital services, those living in slums had poorer access to healthcare compared to the non-slum population; and of the 24 municipal wards surveyed, eastern areas lacked access to healthcare services.[8]

Photo: Aspatal Bachao Nijikaran Hatao Kruti Samiti

Vacant posts ail hospitals

The existing public health infrastructure has been hollowed out by the lack of sufficient doctors and nursing staff. Like the Deonar Maternity Home, a 22-bed facility with a 10-bed ICU and a Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) which has been mostly shut because nearly half of the 50 posts are vacant. It does not have a pediatrician either. “A pediatrician from Anandibai Joshi Maternity Home, Bail Bazar visits thrice a week which means he is absent there on those three days. The hospital sees 12,000 children every year[9] and it does not have a permanent medical officer,” says Supreeth Ravish, a volunteer with the Aspatal Bachao Nijikaran Hatao Kriti Samiti.

Deonar also houses some of the city’s poorest. Along with Govandi, Mankhurd and Vashi Nagar, it forms a part of Mumbai’s M-East municipal ward which has high infant mortality rates, maternal mortality rates, tuberculosis, malnutrition and other indicators of poor public services. The health services are pathetic for its nearly 8.5 lakh population;[10] but the semi-functional Shatabdi hospital with 220 beds was handed over to private players in April 2025.[11]

As high as 36 percent of posts in the BMC’s health services lie vacant.[12] This is a structural issue, points out Dr Shukla: “This is not inevitable, it’s a policy choice. Low spending by governments means not enough staff, no permanent appointments, medicine supply, proper equipment, or hospital maintenance.”

The BMC budget for 2025-26 allocated Rs 7,380 crore – roughly 10 percent of its total budget of Rs 74,427 crore – for health.[13] This is not a small sum but the huge demand for public healthcare – despite the wide availability of private hospitals – makes it inadequate.[14]

The civic body has undertaken the redevelopment of three secondary hospitals – MT Agarwal Municipal Hospital in Mulund, Shri Harilal Bhagwati Municipal Hospital Borivali, and Krantiveer Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Hospital in Vikhroli – but the upgrades are delayed. Worse, its decision to hand over five such hospitals to private players under the PPP model means around 2,500 beds would be available commercially which, in turn, would make accessing nominal cost or affordable healthcare difficult for the middle class and poor who are often one hospital bill away from poverty.[15]

Resource allocation and use hold the power to shift the needle. The Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT)’s “work has shown that when services are adequately resourced, hospitals can reach the poorest and most marginalised without discrimination,” says Amruta Bavadekar, Director, CEHAT. For example, women facing violence, or people seeking long-term treatment, often turn to public facilities first, she adds.

Dilaasa, a hospital-based crisis centre for survivors of gender-based violence, was established in 2000 by CEHAT in collaboration with the BMC’s Bhabha Hospital in Bandra. It is embedded within the hospital which ensures that women access it as part of routine care. And its work has shown that the public health system can be an entry point for gender justice. The model has been expanded to a few other hospitals in Mumbai and offers what the market alone cannot.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Why we need to question the PPP

Even if the private system is left out, the BMC’s increasing embrace of the PPP model means shrinking public facilities. “It took 12 years for the hospital at Lallubhai Compound (a resettlement colony) to be constructed but even before it was opened, it was declared as PPP. The BMC has no mandate to do this because there have been no elections for over three years,” says Supreeth Ravish. Campaigners like him have been fighting, since February, to have the ICU re-opened.

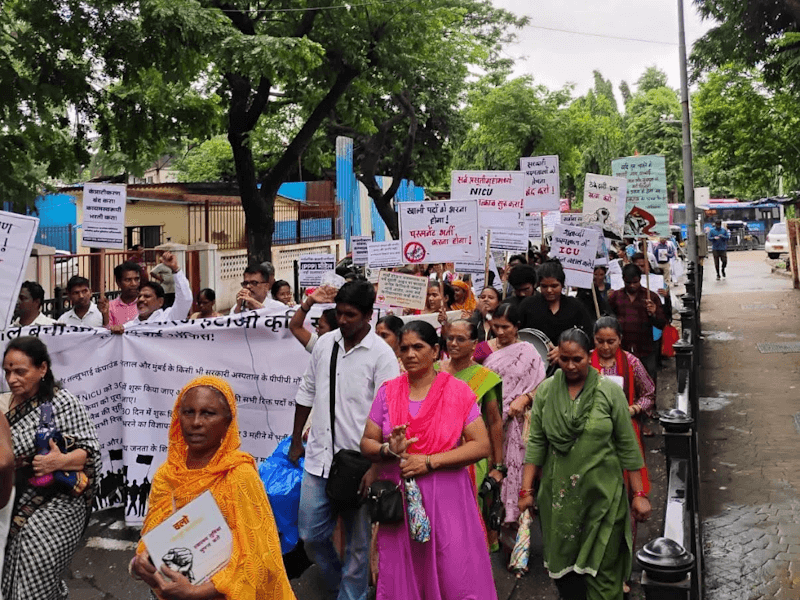

The Aspatal Bachao Nijikaran Hatao Samiti staged protests on July 7 followed by a hunger strike on all these issues.[16] The result? Five Resident Medical Officers (RMOs) were appointed for Shatabdi hospital for six months, and the ICU and OPD were restarted, but there are no guarantees they will function. Such edging out of people from accessing hospitals in their area inevitably leads to over-crowding in the large public hospitals, creating challenges for patients and care-givers.

At Wadia Hospital (charitable, not public), the relatives of children shell out at least Rs 500 a day for meals beyond the treatment costs. Dnyaneshwar Salunkhe, 32, who works in a grocery store in Sambhajinagar (Aurangabad), borrowed from relatives to seek treatment for his infant’s heart condition; he had spent Rs 80,000 on the baby’s delivery back home. “The doctors there failed to diagnose despite five-six sonographies. We were forced to come to Mumbai,” he says feeling lost in the city.

He spent Rs 10-30 a day to use the public toilet and bathroom a lane away and was bracing himself to pay nearly Rs 3 lakh hospital bill after concessions. Kalyan Shinde, 35, a resident of Latur, has run up a bill of nearly Rs 2 lakh for his three-month-old grandson suffering from congenital scoliosis, despite having the state insurance Mahatma Jyotirao Phule Jan Arogya Yojana (MJPJAY).[17]

Photo: Varun Shetty

Right to health

Can Mumbai’s system implement the right to health as a fundamental human right recognised by the United Nations?[18] Quality and equitable healthcare has to be a public good, not a luxury, as the JSA argues. The road ahead, according to its campaigners, is to make this a political issue especially as BMC elections draw near. “Healthcare is a core necessity, and everyone must access it through a publicly managed mechanism. It cannot be properly fulfilled through the private market,” explains Dr Shukla.

Applying the rule of free and low-cost beds in private hospitals, as mandated by law, is also a way forward. As JSA questions, well-equipped private hospitals get away skirting this despite having received subsidies and concessions from the BMC and state government.

Mumbai’s story shows that despite the existence or expansion of the private sector, it is the robustness and resources of the public healthcare system that means the most to people. Healthcare must be on need, not on people’s ability to pay. As Dr Shukla says: “There should be a system of universal healthcare, whether in a public or private hospital. That’s the direction in which we must move.”

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic, and is presently pursuing her Masters in Urban Studies at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Cover photo: Varun Shetty