“There before my eyes were the sprawling salt pans of Mankhurd. The sun was setting on this raw, unkempt, yet beautiful landscape, and it all appeared very magical. A very secluded, almost forgotten part of Mumbai, these salt pans serve as a vital wetland habitat, one of the last refuges of migratory birds arriving in the city in winter, and act as potential buffers against flooding. However, with the urban sprawl gnawing into them with each passing day, their future existence is at stake,” wrote Dr. Oishimaya Sen Nag,[1] a wildlife conservation storyteller, for the Bombay Natural History Society after accompanying researchers to the Mankhurd salt pans to track migratory birds.[2]

This is one of the nearly 40 salt pans sitting quietly across the inland and inter-tidal areas of Mumbai.[3] Spread over 5,379 acres across the suburbs of Ghatkopar, Kanjurmarg, Mankhurd, Bhandup, Mulund, and nearly 2,000 acres in Vasai-Thane, the salt pan lands have high ecological value, support biodiversity, and are crucial for flood control. Salt pan lands lie below the high tide line and hold the sea water that gushes in, not all of which flows back; what remains dries out in the sun and wind, yielding salt and other minerals. In the monsoon, salt pans hold rainwater, helping flood control.

In a coastal city like Mumbai, salt pans are an invaluable natural asset but it is easy to not see their ecological value. The law knew their worth. This is why salt pans, as part of the city’s wetlands, were protected and brought under India’s Coastal Regulation Zone notification,[4] under the classification of CRZ-1B which allowed only salt extraction and natural gas exploration. That was before the Maharashtra government and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) eyed salt pans as potential real estate.

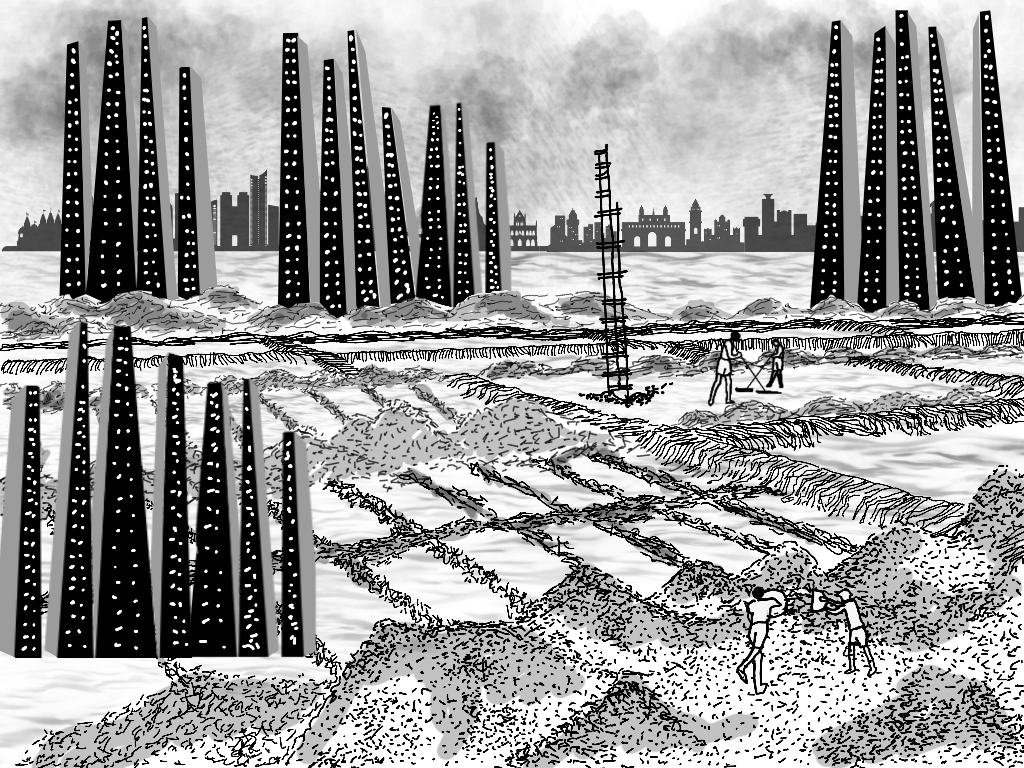

In April this year, the state government sanctioned approximately 256 acres of salt pan lands in Kanjurmarg, Bhandup and Mulund for the Dharavi Redevelopment Project, specifically to relocate people who are not eligible for rehabilitation within Dharavi. The official justification is that these land parcels were decommissioned by the Salt Commissioner nearly a decade ago and tidal water has not reached here in many years; therefore, it was safe to construct on them.[5] Is it really as simple as this, I wondered as I began to ‘see’ the salt pans anew and distill them for the storyboard here.

How the salt pans slipped away from the public

Will the people of Dharavi go nearly 15-20 kilometres away disrupting their lives and networks is a question of social justice but it presumably does not exercise those who have worked out the plan. The displaced-rehabilitated, like lakhs in Mumbai, will be forced to adapt to their new surroundings on salt pan lands. But what of the salt pans themselves? How, if at all, will they adapt to being landfilled, levelled, and constructed upon, with pipes for water and sewage and electricity lines running beneath? What if these wetlands could protest?

This is an ecological question and we must listen to environmentalists, scientists, and others with expertise. For years, this community has protested the brazen plans made for the use of the salt pans and argued on two fronts: That the salt pans are natural and public resources which means their use should not be decided by executive orders of governments, and that merely changing their land use on plans and revenue records does not alter their natural geography and ecosystem. Both arguments have fallen on deaf ears.

The first move to claim Mumbai’s salt pans as developable land came in June 2004 when the Maharashtra government appointed the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) as the implementing agency for their development and, in 2015, tasked it with preparing the Master Plan for the Mumbai Metropolitan Region including salt pans in Vasai-Thane. Its initial surveys in 2016 reportedly revealed that only a fraction of Mumbai’s salt pans could be developed[6] and, ironically, emphasised their importance to counter floods.

However, in 2017, the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests revised the Wetlands (Conservation and Management) Rules, 2017 to exclude salt pans from wetlands. The Mumbai Development Plan (DP2034), in 2018, earmarked nearly 1,781 acres of the 5,379 acres for affordable housing. The Centre also revised the Coastal Regulation Zone rules in January 2019, allowing 1,800 acres of salt pans to be opened for development.[7] Together, the series of decisions eventually allowed for change in the rules at the Centre in August 2024 which enabled the transfer of 256 acres to rehouse the people of Dharavi.

The rules of the Union Ministry of Commerce and Industry, issued in 2012,[8] prohibited use of land under “active salt production” unless for public purposes and in exceptional cases; these conditions were done away with in August 2024. The authorities have been at pains to justify that there was no active salt production in the 256 acres. Even if this were true, what is the assurance that there will not be use of more acreage when the DP itself marked out 1,781 acres for construction?[9]

There’s no clear assessment of what this swathe of construction will mean for Mumbai’s flood management plans and natural drainage of rainwater. There’s no clarity on the comprehensive environmental impact of constructing on the salt pans. Where will the inter-tidal water flow? Assuming the authorities are correct about no tidal water coming in, where will the rain drain out when the salt pans have been constructed upon?

These questions were taken to the Bombay High Court but the PIL, challenging the transfer of 256 acres to the 80:20 joint venture between Adani Group and Maharashtra government, was dismissed in July. The HC stated that there was no solid evidence providing the unsuitability of the land for the rehabilitation of Dharavi’s residents but encouraged the government to incorporate environmental factors when executing the project.[10]

Even if the unsuitability of land for construction could be proved, its full ecological value to Mumbai would still have to be inferenced. Besides, who would decide on its suitability for rehabilitation, would the affected have no say in the matter? This focuses on the interrelationship between environmental rights and human rights.

The life-sustaining salt pans

Environmentalists guess that the non-renewal of salt pan land leases, most of which expired in October 2016,[11] was because of the planned real estate development. The salt pans are a natural flood buffer and help mitigate rain in neighbouring areas. Construction on salt pans removes them as a buffer and could increase flooding in these areas. For example, the Mulund and Bhandup pumping station wetlands collect rainwater and receive inflow from the Thane Creek during high tide, which prevents flooding in the areas of Vikhroli, Kanjurmarg, and Bhandup.[12][13]

The Wadala salt pans are being used by the Customs Department to build a large complex[14] and Kanjurmarg ones were proposed to house the metro car shed,[15] but the 256 acres for Dharavi Redevelopment Project is by far the largest. Although the justification for constructing on salt pans is the provision of affordable housing, it will take considerable expenditure to level and lay out the network for water and sanitation. Besides, like all wetlands, the salt pans host and nurture a treasure of species including birds like common kestrel, peregrine falcon, crested serpent eagle, hornbill, grey jungle fowl, gulls and flamingos — most of which are waders.

Oishimaya Sen Nag’s account documents others like Little Stint, Common Redshank, Terek Sandpiper, Curlew Sandpiper, Dunlin in the Mankhurd salt pans that flew down from the Thane creek during high tide. Salt pans are ideal resting places for the birds since they are large open spaces without much vegetation where predatory birds perch. The channels dug by salt pan workers during salt extraction serve as moats, protecting the birds from land predators like jackals. Will the migratory patterns of these birds change now that their resting spots will be snatched away? There’s a lot of nature at stake here.

‘To imagine lines where none existed’

The threat to salt pan lands does not end with the housing project. There’s nothing to stop the government or the BMC from allotting more of these land parcels for other projects, especially if they are tagged as ‘public interest’ projects and the DP 2034 is held up as justification. Eventually, as climate change impacts intensify and sea level rise becomes a reality, such decisions by profit-hungry developers and enabling governments may well lead to greater flooding in Mumbai. And the people most at risk will be the most marginalised, including those rehabilitated on salt pan lands.

In Dharavi, earlier this year, when I asked people about shifting homes – and entire lives – many of them were migrants who spoke of a sense of ownership about their basti, weaving dreams for their children, confident that Mumbai will not let them down. The chalk marks on their doors, however, told a different story; they would be sent to a distant address belying the claims of Dharavi Redevelopment Project as a ‘social mission’ and ‘a new chapter of dignity’.

In the long arc of city-making, this move to claim and use salt pan lands marks a moment in the ever-changing, often unacknowledged, relationship between land and the sea in Mumbai. Much of the city’s colonial history was occupation and construction of land from the sea and relied on, as historians have pointed out, the belief that two should be divided with hard lines. It gave Mumbai a coastline and its development community a certain vocabulary.

The landmark volume SOAK, by architect-authors Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha, examined this relationship and showed Mumbai to be an estuary with spaces where freshwater and seawater merge. In their exhibition at the National Gallery of Modern Art, in the aftermath of the July 2005 floods, the section Aqueous Terrain proposed 12 initiations to resolve the flood problem not by enforcing the land-water lines but by transforming Mumbai’s spaces to absorb the monsoon and the sea, design interventions that would hold water rather than merely carry it to the sea. Twenty years later, instead of creating such transformations, Mumbai is on the path to shrink a large natural holding area of water – its salt pan lands.

“The flow of water through the life of Mumbai is not just an ecological fact,” wrote Arjun Appadurai and the late Carol A. Breckenridge, noted anthropologists and cultural studies scholars, in their foreword in SOAK. “What we regard as the hard edges between land and sea are produced by a remarkable double helix, of which one strand consists of three centuries of efforts to create clear and permanent lines in a terrain that is forever on the move, as land meets sea, and as saline water meets fresh water in the estuary which was hammered into the shape we now call Mumbai. The other strand is a parallel and necessary exercise in technical efforts to battle, contain, fix, and channel the flows of water in the estuary by the building of bunds, walls, embankments, and the like. In other words, Mumbai’s apparent hard edges are the historical product of a determined effort to imagine lines where none exist and then to make them survive in the face of an aqueous terrain which constantly defeats their materiality.”

How hard a line is drawn when salt pan lands are turned into real estate, only time will tell.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements (IIHS), she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf