Urban festivals are as old as cities themselves. Art and culture have been used as instruments to bring communities closer in large cities with fragmented populations, or used to claim and reclaim public spaces to lend them new relevance, or reflect anxieties about complex issues of our time such as Climate Change, livelihoods, and so on. Mumbai recently played host to three festivals in different neighbourhoods – the Mumbai Urban Art Festival at the city’s oldest dock, Sassoon Docks, focused on the city’s relationship with the sea; the Govandi Arts Festival displaying many talents from the rehabilitation colony in the mostly-forgotten eastern suburb; and the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival which was back on the eponymous area’s streets after a hiatus forced by the pandemic.

Award-winning poet and cultural theorist, art critic and independent curator of several note-worthy festivals, Sahitya Akademi awardee Ranjit Hoskote speaks to Question of Cities about the place and possibilities of art and culture festivals in cities in which he suggests that festivals focus on multi-lingual programming and act as a cultural threshold where people come to terms with the anxieties of our times such as Climate Change.

Photo: Nancy Adajania

What is the significance of neighbourhood or city festivals from the perspective of public places? How do cities benefit when public places are used this way?

My sense of urban art or culture festivals is that they always originate in an agenda of urban renewal or redemption. Take the Venice Biennale as a template. It began as a biennial summer festival in 1895 with the aim of saving a city that had once been important and powerful, but had become a backwater. From being the independent Republic of Venice, a mercantile centre and a hub of culture, it had been battered by successive invasions and then vanished from the horizon in the newly emergent nation of Italy. It was literally sinking, and beset by livelihood issues. The Venice Biennale was invented as a solution to all these issues — to put the city back on the map, to create ancillary livelihoods, and to restore a sense of confidence in the city-image.

Some or all these motifs remain pertinent to city festivals today. In the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival, which I have been involved with since its inception, the heritage motif is very strong but there is also a ‘city image’ argument that this festival advances. As a multi-arts festival, it proposes a way of convening a larger multi-arts community. It was also meant to create a sense of community in the neighbourhood, engaging its inhabitants as stakeholders. Now, my question is whether these objectives have been met or not. Over time, a certain institutionality has become more dominant than bringing the people of the neighbourhood together. Meanwhile, the neighbourhood itself has undergone gentrification, which is yet to be fully addressed by the festival politically.

This, to me, is a question of what festivals ought to be doing: Not only celebrating neighbourhoods for what they have signified in traditional narratives, but inquiring into what future narratives can be imagined for neighbourhoods.

Does a city or neighbourhood festival turn into a fetish which defeats its purpose?

Yes, this is a clear and present danger. The main problem with festival-oriented thinking – with festivalism, as a mode of thought – is that it tends to be event-centric. A great deal of energy goes into a singular event in the calendar, as a high point. It can range from the modest to the spectacular, create a great deal of energy and be inspiring, but I’m not sure what happens during the rest of the calendar. I don’t know about the Govandi festival or Sassoon Docks festival, but with Kala Ghoda, there has long been a discussion about the need for other events and commitments that keep the festival relevant in the larger scheme of things.

As a counterpoint, consider the utsav, the religious festival. It is embedded in an everydayness of consciousness, sensibility, customs and practices, and the festival becomes a heightened articulation of this everydayness, closely connected with it via a feedback loop. With art and culture festivals, my fear is that they become singularities; the rest of the time, the arts community just goes back to its own space doing its own thing in an episodic and fragmentary manner. I wish there could be more of a cogent, coherent everydayness of dialogue and solidarity in the arts community, which then nourishes the periodic festivals where art is presented.

Photo: Kala Ghoda Association

What was your sense of the Mumbai Art Festival or the Govandi Arts Festival?

I missed out on Govandi completely. But I know of the Mumbai Urban Art Festival at the Sassoon Docks. My sense is that there was a strong degree of connection with the actual users of that locus — the communities and fisherfolk were represented, their livelihoods and neighbourhoods represented. This is crucial. Festivals need to be attentive towards the webwork of social interrelationships and the interplay of cultural energies already present in any given site, not only the production of objects and the representation of artistic practices.

The festivals are important also for their use of public space or place which is otherwise not accessed through the medium of art and culture. What are your thoughts on this?

Festivals could, and should, be translating public space into place. But, in Mumbai particularly, as you well know, public space is over-inscribed by invisible protocols of control and surveillance, of ownership and authority, which have come down to us from the colonial regime. This may sound like a banal and practical reality, but anyone who has tried to organise a festival knows how it limits ingenious and experimental use of public space – what it’s like to get literally 50 different kinds of permissions from various authorities. By the time it’s all done, the festival is hardly spontaneous or organic to community life. And I think this is why the use of public spaces, particularly in Mumbai, tends to be very challenging in the festival context.

This already sets a festival up for an event-centric basis, by discouraging the use of public space the rest of the time. How do you occupy these spaces and turn them into places the rest of the time, spontaneously and in an impromptu manner? This would immediately be viewed as a ‘law and order’ problem. It might be important to explore alternative spaces and networks. For instance, somehow, the Bandra Festival used to manage a different kind of a configuration of spatiality and usership. It was also successful in taking back the Bandra promenade from the official domain to a space that citizens had access to. The promenade became a part of community life, a lived space, rather than an official ‘public space’.

Can urban art festivals articulate complex issues such as Climate Change? You curated the ‘State of Nature’ festival last year.

‘State of Nature’ was a forum for multiple expressions across a hybrid platform, which the artist-activist Ravi Agarwal and I co-curated last year. It had an exhibition component, a conference, and a keynote lecture series which addressed different intersecting audiences, on-site and online, while the pandemic regulations were still largely in force. We invited a range of people from different locations, disciplines and preoccupations to engage with questions about nature and Climate Change. It was premised on the hope of a revitalised public pedagogy.

Even within the limits of festivals that tend to be event-centric, it’s possible to raise awareness or to flag urgencies about issues. It is also crucial to adopt a diversity of means of public engagement. In ‘State of Nature’, we included various formats, from lectures to conversations to panels to a multi-media exhibition. What we wished to avoid was the usual jargon-ridden discourse.

Photo: Creative Commons

It is possible to create and curate festivals of art, culture, and literature to engage with existentialist ecological questions.

Absolutely. There is a very strong awareness in literature, the visual arts, and the documentary scene of the problems of the Anthropocene—more correctly, as Jason Moore puts it, the Capitalocene. Having said that, I think the other danger is that the arts cannot and should not be instrumentalised in the service of causes, however noble. Art cannot be reduced to a simple vehicle for conveying ideas and signals of distress. Instead, what arts festivals can do is to act as thresholds or early warning systems – as I have elsewhere described biennials at their best – where audiences can come to grips with the complexity and the diversity of artistic practices, the manner in which they illuminate our lifeworld.

The Govandi Arts Festival was able to create a sense of community, a collective identity. In the fragmented urban life, do festivals help build such an identity?

This might vary from one festival to another depending on what the objective is. With the Bandra festival, there was always a largely productive tension between the old and the new – there was a certain charming ‘Ye Olde Bandra’ quality anchored in the suburb’s traditional East Indian culture, but there was also the recognition of a more plural and contemporary Bandra. The festival managed to meld these two cultural imperatives well but, in general, I am not a great fan of building community identities, whether through festivals or anything else.

This is because the construction of a community identity, especially in a diverse metropolitan context, can have two results. For one, the people within the community could be packaged as exotic and presented for a lazy cultural consumership, which is tragic. For another, community identity can become hard-edged and political along an insider-outsider, us-them binary, which too is unproductive and dangerous. Counterintuitive as it seems, such polarisations are more of a danger in the big cities than in small towns.

Isn’t this something curators negotiate? As someone who has curated for years, what sensitivities would you say curators ought to bring to urban festivals to avoid exoticisation but make people or issues visible?

Curators would have to address this fact to a considerable extent. We are mediating among very different constituencies. Above all, we need to be inclusive in our mode of address, in our programming. It seems like a very simple thing but it hardly ever gets done because so much of what happens in the art world, even when it moves out into public spaces, is primarily Anglophone, all English. We really have to institutionalise a multi-lingual practice in programming and thinking about festivals, at a range of levels.

Too often, cultural festivals tend to land like UFOs in their chosen sites. They should assume the responsibility of understanding the local contexts in which they intervene, and evolve through larger processes of dialogue. To me, the model here would be the work that Ratish Nanda and the Aga Khan Trust have been doing over a decade in the Nizammudin basti and the Humayun’s Tomb Complex in Delhi. Their original mandate was to restore Humayun’s Tomb, but they began with the largest, outermost circle of the neighbourhood by first taking the community into confidence, building capacity in the basti, rebuilding people’s houses, dredging a stepwell, making sure the community had access to amenities, education and livelihoods, and then gradually moved towards the restoration of the monument, enlisting the community as committed participants in the process – not as baffled onlookers or bemused bystanders watching change take place in their own area. This is the kind of long-term engagement that we need.

There are other kinds of interventions that offer exemplars. The amazing Cybermohalla project of the early 2000s, through which the artist-curators of SARAI-CSDS collaborated with young people in some of Delhi’s bastis. There are other kinds of curators, like Parag Tandel who belongs to the Koli community of Mumbai. In collaboration with his wife and fellow researcher, Kadambari Koli, he has been working on a project of building archives of the community’s historical memories, folklore, customs and practices, and their role in the history of Mumbai. That’s another way of building a bridge between cultural practice and political commitment.

Do urban festivals open up certain areas to the ‘outside’ world, make certain places on the city’s map more prominent than they used to be, as in Govandi?

I don’t know enough about the Govandi Arts Festival or the British Council’s concerns or motivations there. But with any precinct that a festival aims to “put on everyone’s map”, my question would be: To what end; what is the purpose of such an intervention? I say this because when we say that we would like to open a place up to the outside world, we must remember that no one is really isolated in a city. People live in Govandi, they have their own forms of connection and interrelationship to the world outside. If that neighbourhood is meant to now become the focus of cultural attention, my question would be, will this somehow build capacity there and create a sense of participatory agency? Or will the neighbourhood become another neo-exotic destination for cultural consumers of difference and otherness?

Photo: Creative Commons

Have urban festivals, from Venice Biennale to contemporary festivals, brought about social or structural changes?

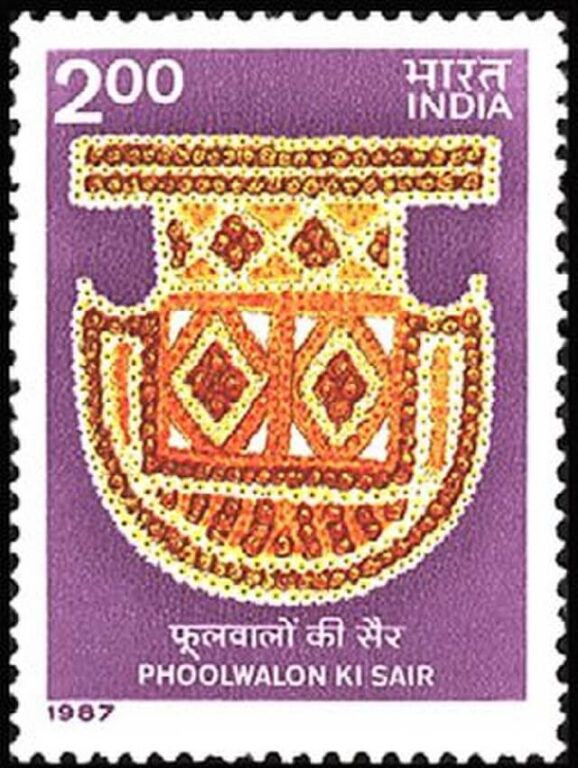

At least, there is the hope that they will bring about social and economic change. We think about Venice because it’s such a major paradigm in this template and it has been around since 1895. There have been other cultural initiatives that are barely remembered. As India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, with his advisors, restarted the Phoolwaalon ki Sair in old Delhi, a Mughal-era annual event that had disappeared after 1858, when many of Shahjahanabad’s cultural practices were suppressed by the colonial regime. Recreating it was a way of instilling confidence, restoring heritage, and building livelihood in an area that had borne the brunt of historical violence. And the motif of bringing attention of the world to something relatively isolated.

So, I think we have many different starting points and examples, but wherever we look, the aim or at least the hope is that such an intervention will bring about some kind of concrete transformation, social or economic. The tragedy is that, as with any kind of institution, festivals become preoccupied with perpetuating themselves, raising funds, adapting to the desires of funders, managing the precarious balance between commitment and prestige, and so forth.

Photo: Creative Commons

Do urban festivals also hold the possibility of disruption, making people thoughtful or uncomfortable about issues?

It really depends on the individual edition. All festivals make certain claims or have a mission objective, but the degree to which these are accomplished is a function of temporality, and varies from one edition to the next. The degree to which a festival can disrupt and open up new conversations is not something that you can predict even though you might devoutly wish it to happen. If a festival is to allow for creative freedom, it cannot, paradoxically, lay down the rules too firmly on how its curators should embody the festival’s aims in their work.

But installations and performances can spark off ideas and reflections in viewers about, let’s say, Climate Change.

There is certainly a need to make room for visceral provocations in urban arts and cultural festivals. It would call for a courageous use of public space because, for the duration of the festival, public space becomes a forum, a place for congregation, collective experience, feeling-thinking-response-debate as a continuum.

Cover photo: Venice Biennale by Rui Alves/ Unsplash