At the start of summer in April, the India Meteorological Department forecasted a summer with “higher than usual temperatures”[1] but what followed through April and May were more hot days than ever with increased frequency and intensity. Delhi’s Mungeshpur weather station recorded 52.9 degrees Celsius, the highest ever in 80 years, and became the stuff of urban folklore. In the heated talk, many glossed over the simple correlation between rising temperatures and reducing tree cover.

In Delhi itself, trees in the heart of the city continue to be wiped out and supposedly transplanted[2] However, Delhi is not alone, other cities have seen a steady erosion of green cover due to rapid urbanisation and the emphasis on mega infrastructure projects; Mumbai lost a staggering 2,028 hectares of green cover in only five years between 2016 and 2021, according to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan.[3]

Other cities show similar trends. The India State of Forests Report noted that Ahmedabad lost 47.6 percent of its green cover between 2011 and 2021[4] while it experienced 28 heat waves between 2008 and 2019, and recorded its hottest day since 1897 at 48 degrees Celsius in 2016.[5] A study of Chennai Metropolitan Region between 2013 and 2022 observed that it lost 13.33 percent of vegetation and saw an increase in temperature by a staggering 6.53 degrees Celsius.[6] The Global Forest Watch recently reported that India lost a total 2.33 million hectares of tree cover between 2000 and 2023 which resulted in the emission of a staggering 1.12 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.[7]

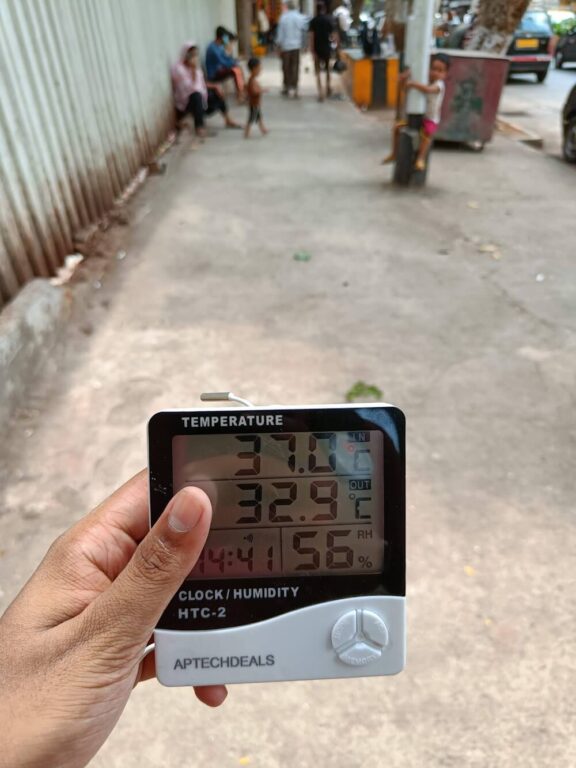

Photo: Vedant Mhatre

Abundant green cover helps to heat-proof cities. Within a city too, areas with trees record lower temperatures on hot days than neighbouring areas without them.

Extremely high temperatures of the kind seen this summer – an average of 8-9 degrees Celsius higher than normal on certain days – affect everyone but they mean the difference between life and illness, or life and death, for millions who work outdoors. This, studies show, is nearly 330-350 million Indians, primarily from low-income or low-caste groups, according to reports. Only 8 to 10 percent[8] of Indian households own air conditioners which, ironically, consume power which means more fuel burning and emissions.

Bengaluru’s decision to keep parks closed during afternoon hours[9] drew wide condemnation. Gardens, parks, shaded open spaces, drinking water facilities, and easy access to shelters are all mitigation measures to combat heat. This study linking urbanisation to rising heat[10] argues that Indian cities should follow a different approach to city action plans. A study of 93 European cities by Lancet in 2023 found that 30 percent green cover could reduce heat-related mortality by a third.[11] Ambient temperatures and shade play a crucial role in keeping a neighbourhood cool.

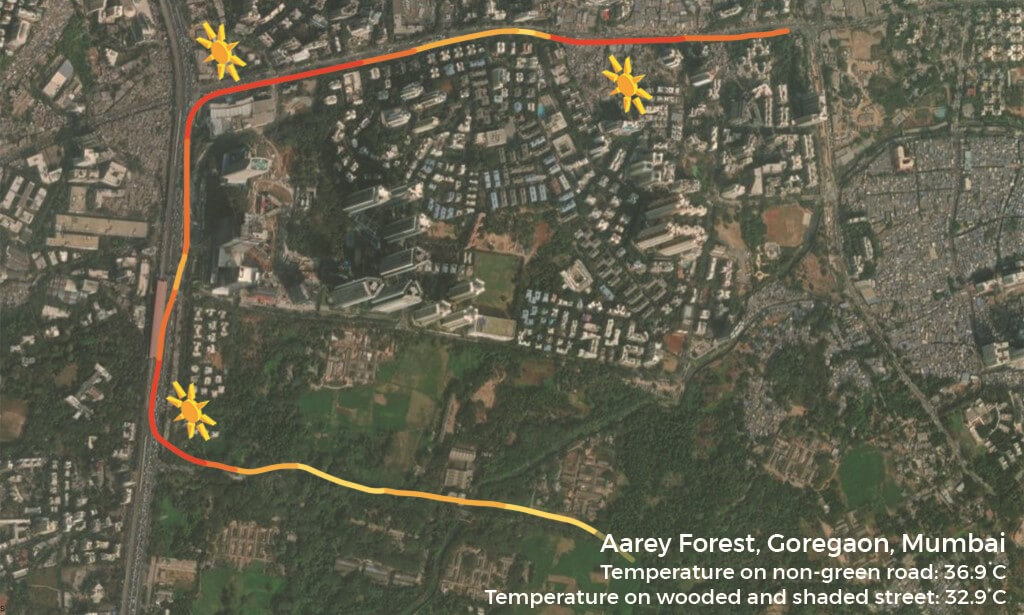

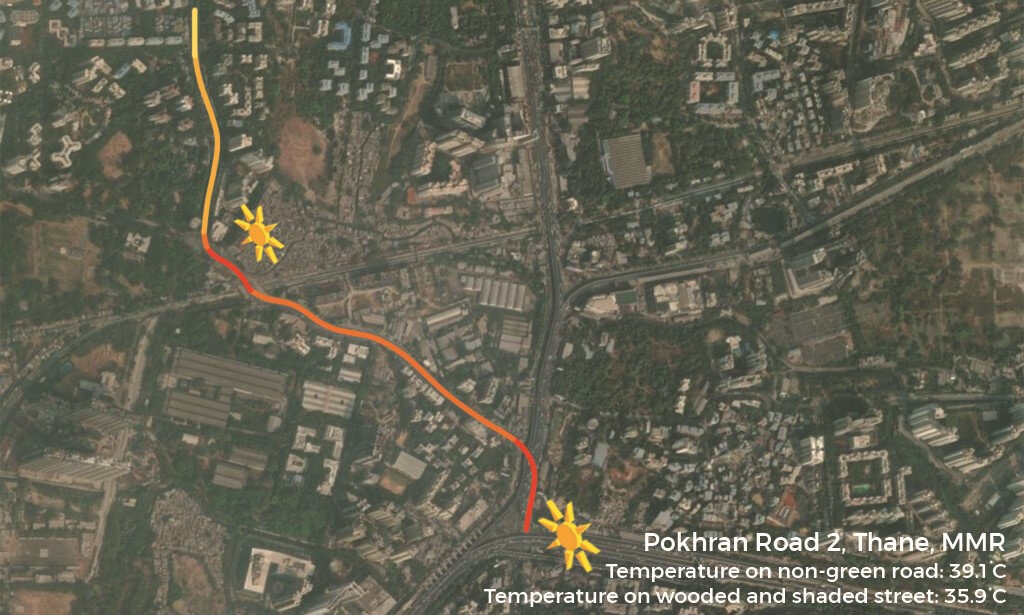

To see how this works on the ground, Question of Cities mapped temperatures on selected streets in cities in the latter half of May as daytime temperatures broke records. In Mumbai, we mapped streets in Goregaon, where Aarey forest is situated, and Byculla which has the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Botanical Udyan. The mapping extended to the fast-urbanising Thane and Dombivli. In Kolkata, we walked from Deshapriya Park towards Rabindra Sarobar, south Kolkata’s largest and well-protected open space. Delhi’s Aruna Asaf Ali Road showed a stark difference of temperature in stretches with and and without tree cover.

Photo: Vedant Mhatre

Natural areas are oases

In Mumbai’s Goregaon, the Aarey Road and General Arun Kumar Vaidya Marg are situated just off the Western Express Highway. Barely 900 metres apart, the two roads have starkly different levels of tree cover. The temperatures on the Vaidya Marg’s tree-lined half averaged 34.8 degrees Celsius whereas the more concretised half towards the eastern side averaged 35.7 degrees Celsius on May 21 during the same hours. The highest temperature mapped was, not surprisingly, along a treeless part of this road at 36.9 degrees Celsius. While this road has parks, they were all shut which effectively kept people away from shade.

In contrast, the thickly tree-lined Aarey Road, practically through the remaining forest, registered an average of 34 degrees Celsius on the same day. The lowest here that day was an astounding 32.9 degrees Celsius – four degrees lower than the highest. Even within this small microclimate, sections of the road near large canopies were cooler.

Similarly, in south Kolkata, the difference in temperatures on the walk from the busy Deshapriya Park towards a large and well-protected urban common on May 24 was astounding. In the absence of shade at the Deshapriya Park intersection, pedestrians jostle with vehicular traffic in the glare of the sun; this junction recorded 37 degrees Celsius. The road towards Lake Terrace, with scattered trees, registered 36 degrees Celsius at the same hour.

Photo: Srestha Chatterjee

Further ahead, the temperature dropped to between 34.3 and 35 degrees Celsius in the lanes surrounding Lake Road and towards Dr. Sarat Banerjee Road, registering 33 degrees Celsius as we moved closer to Rabindra Sarobar. The temperature recorded at Debaki Kumar Bose Sarani, on Lake Gardens Road, was 30 degrees Celsius, a full 7 degrees lower than at Deshapriya Park junction with no change in day or time of readings. The heavy presence of trees here also meant shade and cool breeze.

Urban density and heat

In Dombivli, a large suburb in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region, we compared a circuitous internal road within the lush green Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC) residential zone with a tree-less section of the main Kalyan-Shil Road a few hundred metres away on May 20. MIDC is home to thousands of residents, five major hospitals and six schools – not a low-density area but the tree cover is significantly thicker than on an average Mumbai street.

Photo: Vedant Mhatre

The temperature averaged 38.3 degrees Celsius for the wooded section whereas the section without trees averaged 40 degrees Celsius at the same hour. Similarly, peak day temperatures of 37.5 degrees Celsius and 41.5 degrees Celsius were recorded in the tree-lined and tree-less sections respectively. Consistent with other locations mapped, we recorded a variance of at least four degrees Celsius between areas with and without trees despite the density.

A field survey carried out by a student across 89 locations in Ahmedabad found that parts of a road under tree shade were 6-8 degrees Celsius cooler than the rest of the road. A shaded street’s temperature as recorded by an infrared thermometer was 31.2 degrees Celsius while the unshaded street recorded a temperature of 39.9 degrees at the same hour.[12]

In Mumbai, the famous Saat Rasta in the densely-populated erstwhile mill area has KK Road which leads to the Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Botanical Udyan or Rani Bagh spread over 60 acres. On the ES Patanwala Road running along the verdant woods, people were seen napping under the shade of the trees on the footpath. A short distance away, three roads – Tank Pakhadi Road, Barrister Nath Pai Road, and Maulana Azad Road – lack the kind of tree cover seen on KK Road and ES Patanwala Road though they lie close to Chinchpokli and Naralwadi – tamarind groves and coconut grove respectively.

In the area, the average temperature recorded on roads with a good tree cover was around 33.2 degrees Celsius and a whole degree higher at 34.2 degrees Celsius on roads without trees on May 21. The difference between the lowest and highest readings that day at these places was 3.6 degrees Celsius. This finding was unexpected in an area where the sea typically moderates temperatures significantly.

Kolkata and Delhi show same pattern

The difference may not have been this stark near the Bengal Rowing Club in Kolkata but the absence of adequate tree cover on the bridge leading to Prince Anwar Shah Road saw a rapid rise in temperature from 31 to 33 degrees Celsius. The air on the bridge, exposed to sun without trees as a buffer, felt thicker and suffocating from the emissions of the vehicular traffic which did not get absorbed or cleaned by trees.

Though it was largely observed that affluent areas of a city had a better tree cover, this did not hold true for Aruna Asaf Ali Road in south Delhi on May 27. Workers sitting under trees here had to endure an alarming maximum temperature of 50.8 degrees Celsius whereas a stretch on the same road without trees saw an unbelievable 63.4 degrees Celsius. Our cities are melting, becoming increasingly unbearable, for those engaged in outdoor work and physical labour.

Thane city, adjacent to Mumbai, is among the fastest-growing urban areas in India. Its Vasant Vihar neighbourhood has many gated complexes and the Gladys Alvares Road, which runs through the neighbourhood, is a walker’s dream with a remarkable tree cover on both sides and wide cool footpaths. The temperature here averaged 36.6 degrees Celsius with the lowest recorded 35.9 degrees Celsius on a day. It was not unbearably hot.

However, the landscape changed drastically at the intersection with Pokhran Road 2 which lacked adequate tree cover. The temperature here was around 38.6 degrees Celsius. Several women sat wherever they found shade because the informal dwellings turned unbearably hot. Moreover, the temperature peaked at 39.1 degrees Celsius, a whole 3.2 degrees Celsius higher than the lowest temperature at the nearby Majiwada junction.

The arterial Jogeshwari-Vikhroli Link Road in Mumbai, connecting western suburbs to the eastern, is a traffic nightmare. It passes by IIT Bombay as it winds to Vikhroli. The premier institute’s campus, as is well known, is among the most picturesque and environmentally-rich campuses in India. Our mapping showed that the internal roads of IIT Bombay were at least 4 degrees Celsius cooler than the Jogeshwari-Vikhroli Link Road outside the main gate.

Fewer the trees, hotter the city

Across the cities we mapped, the outcome was clear: Areas or roads with fewer or no trees were hotter at the same time on a given day.

This paper[13] co-authored by Harini Nagendra, professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University, found that mean tree street density was low in Kochi as well as Panjim. By assessing the abundance, distribution and diversity of street trees in the two coastal cities to understand the status and perception of green spaces in the city, this study ranked Panjim higher than Kochi in roadside tree abundance and diversity. Additionally, the tree density per kilometre varied too (64 in Panjim, 14.5 in Kochi). The density of the tree cover makes Panjim cooler than Kochi.

Trees on streets help mitigate urban heat and reduce the risk of high heat exposure – by almost 2.57 degrees Celsius in a South Tacoma neighbourhood, according to this study.[14] It also found the “probability of daytime temperatures exceeding regulated high temperature thresholds was up to five times greater in locations with no canopy cover within 10 metres”. Severe heat exposure is a public and occupational concern, and “there is a need to understand the effects of urban tree planting at the local and human-scale,” the study argues.

The importance of trees in cities cannot be overstated. As our mapping showed, trees in an area keep it cooler. Trees absorb water from the soil and release the hydration through their leaves in a process called transpiration, which helps keep the surroundings cool. We don’t just need more trees, we also need less concrete in cities. By studying daytime and nighttime temperatures, researchers found that the amount of impervious space has a great impact on temperature too and argued that reducing nighttime temperature is especially important for bodies to recover from daytime heat during heat waves, which makes planting trees a necessary addition to climate mitigation strategies.[15]

Are India’s urban planners and politicians listening?

With inputs from Srestha Chatterjee (Kolkata) and Avinash Chanchal (Delhi).

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Vedant Mhatre, activist with the Walking Project, passionately explores the complexities of the modern urban landscape, focusing on urbanism, transportation, and climate issues. Adept at crafting online campaigns to drive attention to urban challenges, he creates and uses informative videos on these topics to drive home the point. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Electronics Engineering.

Cover photo: Vedant Mhatre