You have been practicing since 1991, the year of liberalisation in India, and are known as a public-minded medical practitioner with work in public and private hospitals, and also community organisations. What has been your experience?

Honestly, I don’t want to talk about myself. By the time I finished my MBBS in the mid-80s and postgraduate in surgery in 1990, I was already connected to people working in the social sector, trade unions, slum organisations and so on. Inevitably, it started reflecting in some of my work and choices. For the first 10 years, I worked at KEM as associate professor in surgery during which I got a scholarship in England to train in liver transplantation, returned and spent two-and-half years trying to set it up at KEM. Soon, I realised that it’s complex and demanding, and there was not much institutional will too.

In about 2000, I joined Jaslok Hospital, a private charitable hospital, and an civic peripheral hospital at Bandra, KB Bhabha, from where I superannuated in 2022. It was a double life. Private and public medicine in India are two shockingly different worlds. They sit next to each other but serve two different sets of people. Right from my KEM days I was involved with many social organisations. Dr Sunil Pandya, who passed away last year, had started a publication, the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics.[1] For a few years, it was small but it got noticed because we were a group of doctors willing to speak out on ethical distortions in the practice. We took a public stand on many issues.

Tell us more about that.

About 50-60 years ago, the relationship between a doctor and a patient in India was personal, a close bond. The neigbourhood doctor would help with very basic healthcare. Over the years, a distance developed. It had to do with the evolution of healthcare both in its complexity and as a market. Costs went up, technology came in, complexity increased but regulation was poor. People began to doubt doctors. That’s the erosion I am talking about. But we have also had a fair amount of activism in healthcare.If you’re a doctor practicing in India and you don’t get a sense of inequity, then you must be stone-hearted. Many doctors slowly got disillusioned too.

The Journal became a platform for many in India who were uncomfortable with the trajectory of healthcare. Simultaneously, it became an academic journal with peer review, acceptance or rejection. Now, it is the only journal from India on medical ethics and unique in South Asia. It got noticed globally and indexed. It’s well established now. People write for it partly because it’s a platform but also because it’s academically recognised on multiple prestigious databases.

It gave me an opportunity to start writing. After my first few pieces, I was approached to write in the public domain and, to my surprise, people seemed keen to read. I have now written for The Indian Express, The Times of India, The Hindu, Scroll, The Wire. Then, Mumbai Mirror approached me to write a weekly column, coinciding with the COVID. I conveyed what I was seeing around me at work. Many told me it was a unique insider view, a working doctor’s ringside view. Now, I am also involved with other journals including on the editorial board of the British Medical Journal. These networks, connections, public writing, identifying with social issues, while dealing with the contradictions and stark reality of my work, allow me to vent out but also push for reforms. I was asked to be on a high-level committee to promulgate law for regulating healthcare in Maharashtra.

It’s a complex situation of transition from public healthcare to private, both at a personal level and in post-liberalised India. Tell us about this complexity – the melting down of the public and the rise of the private sector.

This is a very complex question and must be first viewed historically. Around independence, there was a plan for India like the National Health Service in Britain. In my view – I have worked there – the British have one of the best public-oriented, tax-based, public-funded healthcare systems in the world, despite the recent slowdowns. Many aspects of the public in Europe have been privatised but not healthcare. The Bhore committee[2] had recommended an NHS-like plan for undivided India. After independence, India started out with a large public sector healthcare. It was partly Nehruvian and Soviet influence that healthcare was seen as a public good.

Scholars show that privatisation accelerated after liberalisation; it had started much earlier. This has to do with many factors. Firstly, the government decided to focus on primary and secondary care, which was necessary in a newly-independent country, but did not invest beyond this. But there was a need for curative tertiary care technology and specialisation. This space was slowly filled by private interests. The elite created their own facilities.

There were other types of hospitals. Those run by Christian missionaries, some of them fine institutions like Christian Medical College in Vellore, St. John’s in Bengaluru; faith-based hospitals like Holy Family in Bombay and Hindu businessmen- philanthropists building hospitals like the Bombay Hospital which was basically the Birlas, the Hindujas, and the Chanrais who built Jaslok; then, community hospitals like the Bhatia Hospital and Saifee Hospital; and, lastly, many small private nursing homes, individual doctor-owned, which is unique to India.

In the 1990s, with the opening of the economy, there was an almost open invitation to private money, even global investors, to invest in healthcare. That’s because the government had not invested enough. In GDP per capita terms, India’s spend on healthcare is one of the lowest in the world. I daresay that governments collectively did not take healthcare seriously and left it to the vagaries of the market. But it never became a serious political issue. Though socialist governments in many countries made major strides in healthcare by investing heavily, in India the Left-led governments could not.

It is a theory, and may sound dangerous, but governments not investing enough in a big country with rampant disease could be because of our dominant philosophy of Karma, fate, and destiny. Disease is seen as God’s curse or fate. Only when disease is seen as an impediment to society flowering into a vibrant and healthy one, will it be seen as the state’s responsibility to make people healthy. We have normalised two different worlds in healthcare – the under-funded public system with long waits and poor sensitivity to patients and the private one which runs on money, speed and technology. It’s like, in Mumbai, 8-10 people die every day falling off local trains is accepted as normal while the focus is on posh roads for cars.

This is class-based, isn’t it?

Yes but also inefficient, unhygienic and unfriendly. There are studies about why even the poor head to private hospitals. In Mumbai’s Bhabha Hospital, if I asked for a set of investigations, they would be given three different dates. A daily wager or slum person cannot come on three days because it means loss of income. The private hospital is expensive but fast. People find it efficient compared to long waits because of the under-funding of public hospitals. The point is if we have two unequal systems, unequal in the way care is delivered, we push people towards the private sector. There are two stark facts. One is that India has one of the most privatised healthcare systems in the world; 70 percent of the beds are in private hospitals. This is unprecedented. Two, more worrying, is that India is among the countries in the world with the largest proportion of patients paying because the insurance penetration is low.

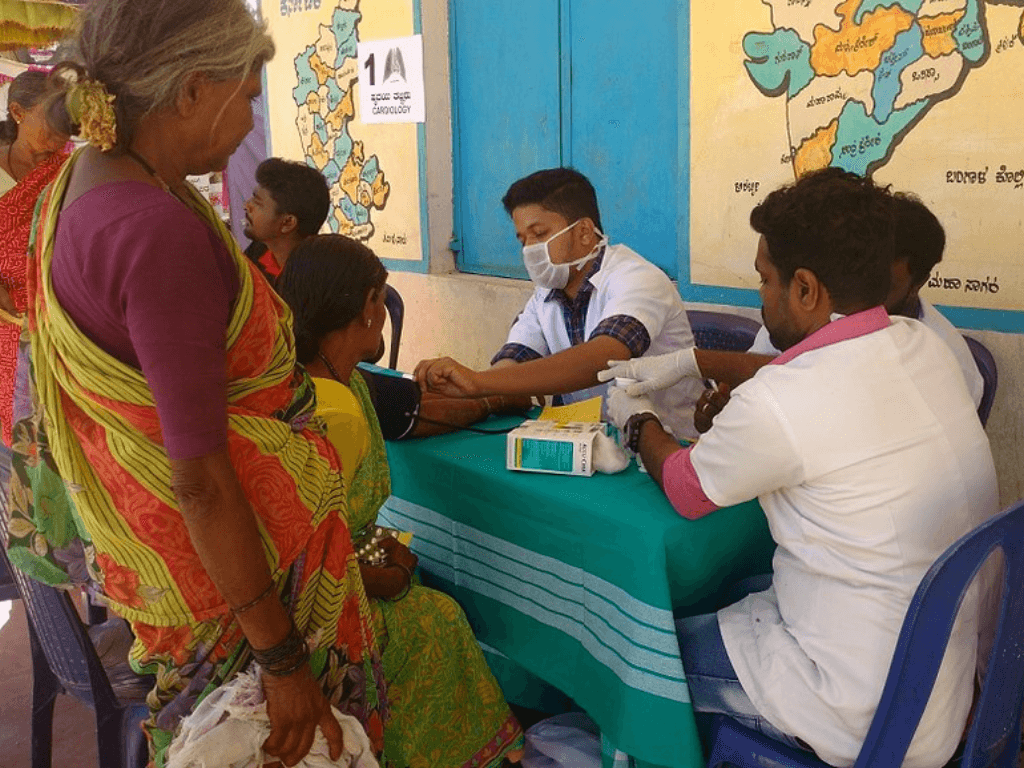

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The PM-JAY or Ayushman Bharat is promoted as the world’s largest health insurance scheme with a cover of Rs 5 lakh per family per year. Is it working?

PM-JAY, a mass insurance scheme, is an experiment for the state to buy care from the private sector. I have written on this. It is temporary relief and financial protection for the poor which is important because personal insurance hovers around 7–8 percent in cities, but it’s barely 4–5 percent outside, and employee insurance another 10–20 percent. There was no health protection for many people. PM-JAY attempted to fill that and reportedly covers 40–45 percent of the population. We are just beginning to understand its impact which is mixed.

Out-of-pocket expenses for healthcare in India are unprecedented and lead to penury, debt, and even suicides. People sell homes or land because of a major illness. India has one of the highest rates in catastrophic expenditure in illnesses. This is a spectacular collective societal failure – not just about creating hospitals but also not giving protection to individuals. Rural areas, of course, have limited facilities but it’s so even in Mumbai’s Govandi and Mankhurd. The 25-26 peripheral hospitals are under-funded and, therefore, under-utilised. So, the load is on large public hospitals like KEM, Nair and Sion hospitals. For those who experience both systems, it’s dark, but we have accepted the ‘two Indias’. It’s worrying, especially in healthcare, because it means you get better care in one and less in the other. However, the private sector may over-treat because it’s about making money.

How do doctors respond in these situations?

Most doctors are happy about increasing privatisation. It’s about working with better technology, in better conditions, making more money. It’s unrealistic to expect that most medical students join the field to serve the poor. Society signals everyday that money matters. The Indian medical fraternity will do lip service, our associations do take a stand, that there should be more public funding but, intrinsically, there is no major opposition to privatisation. Many joined medicine with the idea of working in the private sector or having their own hospitals, very few for the love of science or as public service.

In India, there’s another peculiar thing. I don’t know the percentage but many doctors have a direct stake in their practice. In the rest of the world, doctors work with hospitals; here, you own the hospital, nursing home or clinic. It leads to conflict of interest. With exceptions, of course, but medical professionals here are largely happy to be entrepreneurs, and they are recognised by society too. Medical entrepreneurs like Prathap Reddy, Naresh Trehan and Devi Shetty, all successful healthcare entrepreneurs are seen as policy experts.

Tell us more about Ayushman Bharat expanding the insurance coverage to about 40 percent and why the idea of peripheral hospitals, which is decentralised healthcare, did not work.

I meant peripherals specifically in big cities. A good example is the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) in Mumbai though the state government also runs the JJ group of hospitals. It has four hospitals with medical colleges, smaller peripheral hospitals, health posts and dispensaries. So, it’s a multi-tier system with a referral system but this has never worked. The medical colleges were active, good, and reputed. I studied in GS Medical (KEM Hospital). Because of their long history, students, and visibility, they were relatively favoured by the BMC. On the other hand, peripheral hospitals were not delivering. As a result, people had to travel to the bigger ones. Also, Mumbai’s population moved to or grew in the suburbs while the large hospitals, except Cooper, are all in the city.

When I was working in Bhabha, I would raise many of these issues and realised that the large hospitals take away funds. For example, Bhabha gets many trauma victims of road and railway accidents, and violent incidents. It did not have CT scan facilities which are basic for assessing head injuries. I was very upset, raised this with the superintendent, then with the area corporator Karen D’mello. She took it up and brought it up in a big way in the BMC Health Committee as a member. Till then, all the CT scan requisitions were sent to the nearby private diagnostic centre.

I asked Karen to push for it. Another corporator, Asif Zakaria, also helped. Finally, the BMC shifted a CT scanner lying in Bhagwati Hospital, Borivali, to Bhabha. I suggested she campaigns on this in her election, she did but she lost. What I’m saying is that healthcare has not been on the political agenda. I once wrote about this in a piece titled Slumdog Hospital—these hospitals are seen as places for slumdwellers and, therefore, under-developed. They are peripheral in the mind because they serve the poor and, in the case of Bhabha, minorities.

And the PM-JAY scheme?

We love schemes. Healthcare works as schemes because it has symbolism and schemes have political dividends. But governments should deliver routine care. The earliest precursor of state-sponsored mass health insurance was Aarogyari, in Andhra Pradesh by the late YS Rajasekhar Reddy. He apparently reaped political benefits. Other governments and political parties replicated it. Maharashtra had the Rajiv Gandhi scheme now called the Phule Yojana. At the national level, there was Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana[3]. They funded specific healthcare packages mainly in government hospitals but it’s anyway supposed to deliver care.

The PM-JAY is a leap forward. There are two-three things. One, people can get a card online, if eligible. Two, it gives Rs 5 lakh protection to a family per year. Three, they can use it for treatments and procedures in private hospitals. And, 40 percent of the population is covered. For cancer care, the PM-JAY supports the national cancer grid which has about 20 hospitals. Of course, there are challenges. It’s largely for procedures, the monitoring is poor, and many private hospitals do not honour it. But, as I said, when the market enters healthcare, it’s prone to excesses; now the government is paying, so excesses and frauds are seen.

But this insurance-based model is not a replacement for good public healthcare; it’s tacit acknowledgement by the state that it cannot provide healthcare, so it’s giving you money to go to the private hospital. I have sat in national committees on PM-JAY and senior officials acknowledge this point. They know the private sector is unnecessarily pushing costly stuff and excess billing. That is the essential revenue model of the private sector in health – create demand and over-treat. Now it’s making money from the government but, yes, common people are benefitting though we don’t know the extent.

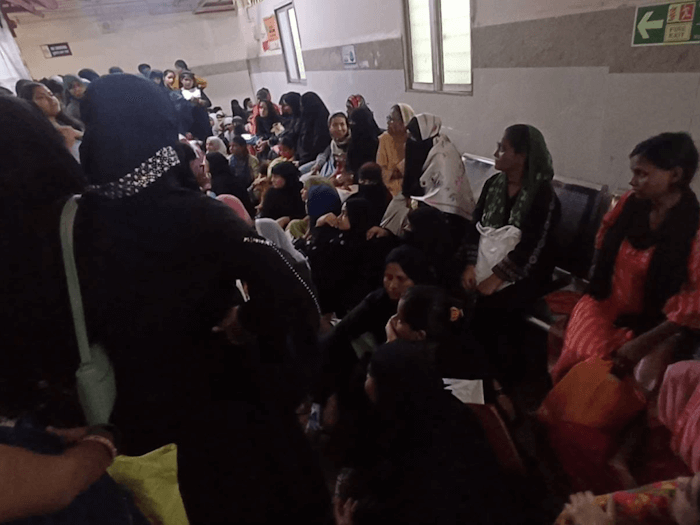

Photo: Harshada Borade

Insurance is not the same as accessing healthcare in public hospitals.

Of course, this insurance scheme with the government supporting healthcare in private hospitals means it’s not building its own capacity. Access for the public may have improved but the empaneled hospitals are in certain places only, so access has not improved access for all. The data is mixed – Tier 2 cities are better off than rural areas – but something is better than nothing. It’s like giving Rs 5 lakh ex-gratia to accident victims; it’s some relief to families but it’s not the same as providing ambulances for emergency medical accident victims, building better roads, making safer vehicles to prevent accidents.

Many state governments now have such schemes because there are electoral dividends but I doubt if it will improve public healthcare infrastructure because there’s no investment in it. Mumbai should have had 20 more KEMs; the doctor-patient ratio in the public sector is still very low. We need 10 to 12 massive public hospitals in the suburbs with all facilities in-house. This has not happened. There’s a slow push now but it’s probably late because people don’t identify specialty care with public hospitals. The BMC faces another, more complex, challenge of retaining doctors and nurses. The reason is obvious – there are two unequal systems and one pays more. Also, the private sector gives you a certain ‘freedom’, the technology and working conditions are better. It’s a worrying dichotomy. Everyone wants to be educated in public medical colleges but work in the private sector.

Private hospitals run by charitable organisations not setting aside a certain percentage of beds, a statutory requirement, has been documented. How can this be changed and which authority is accountable?

The authority is clearly the Charity Commissioner. I treat a lot of patients under the scheme, so I have a sense of what’s happening. The provision is under-utilised. There are many hospitals like this. They have to compulsorily treat 10 percent of patients in two categories-–subsidised and free—by setting aside a part of their profits as quid pro quo for the many concessions they get from the government. It’s a good scheme though its impact on a city of Mumbai’s size can only be limited. Many doctors are not interested in this scheme, they rarely tell poor patients about it. The poor are not aware of this scheme. Even if accidents happen in front of these hospitals, victims are taken to public hospitals far away. After a recent Pune incident in which the pregnant woman lost her life, Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis announced that the government will take over these ‘charity’ beds.

In Mumbai, didn’t the BMC assert itself over private hospitals during Covid-19?

Yes this was part of the Mumbai model as it was called. The then Municipal Commissioner IS Chahal said the private hospitals have free beds, so they cannot refuse admission to COVID patients. During COVID, many unprecedented things happened. For the first time in India, treatment costs and ICU costs in private hospitals were capped and monitored by governments. But this stopped after COVID. For those over-charged, a state-level campaign managed to get hospitals to refund. Dr. Abhay Shukla did a lot of work on this.

I believe that healthcare cannot be done through charity and philanthropy; it has to be mainstream intervention of the state. Philanthropy doesn’t solve healthcare, it’s good intention but symbolic. Even in countries of the Global South too, those who have done well in healthcare have state-funded, universal healthcare as the dominant form, and high public investment. Good examples in South Asia are Sri Lanka and Thailand.

Nobel Laureate Dr Amartya Sen believes Buddhist countries invest more in healthcare because they are more equal societies, although the Buddhists in Myanmar killed their own and sent the Rohingyas out. Latin America, of course, is more developed on this front. I was recently discussing with Brazilians their healthcare structure. Brazil is a high population country but its health parameters are way better than India’s. It’s highly decentralised and hardly has anything called private healthcare.

Globally too, the private sector is at the fringe of healthcare except in the United States. But people don’t realise that, in the US, no one pays out-of-pocket and almost everybody has insurance. Above 65, you’re covered by Medicare and Medicaid. So, healthcare is market-based but well regulated. India has a peculiar combination of highly privatised care that’s also unregulated. I can start a hospital in the building next door even though there are six in the area, call it ‘world’s best,’ and no one can stop me. So, it is really about government intervention and social solidarity.

You mentioned COVID-19 and Mumbai. How do you assess the Mumbai Model which got a lot of publicity?

What is the Mumbai model? It’s how many countries normally do public healthcare. We were pleasantly surprised because it was new from the BMC which created a system called triage based on severity of infection. There were three levels and patients would be admitted depending on severity. The second thing was it had this centralised bed management where people could dial a BMC number and they would be told which hospital had beds. Then, the Maharashtra government put cost caps on private hospitals. For the first time, the rich too had to wait for medicines and beds because it was centrally decided on patients’ severity and people were directed to a hospital in the area where they lived. There was public outreach. It all seemed to work.

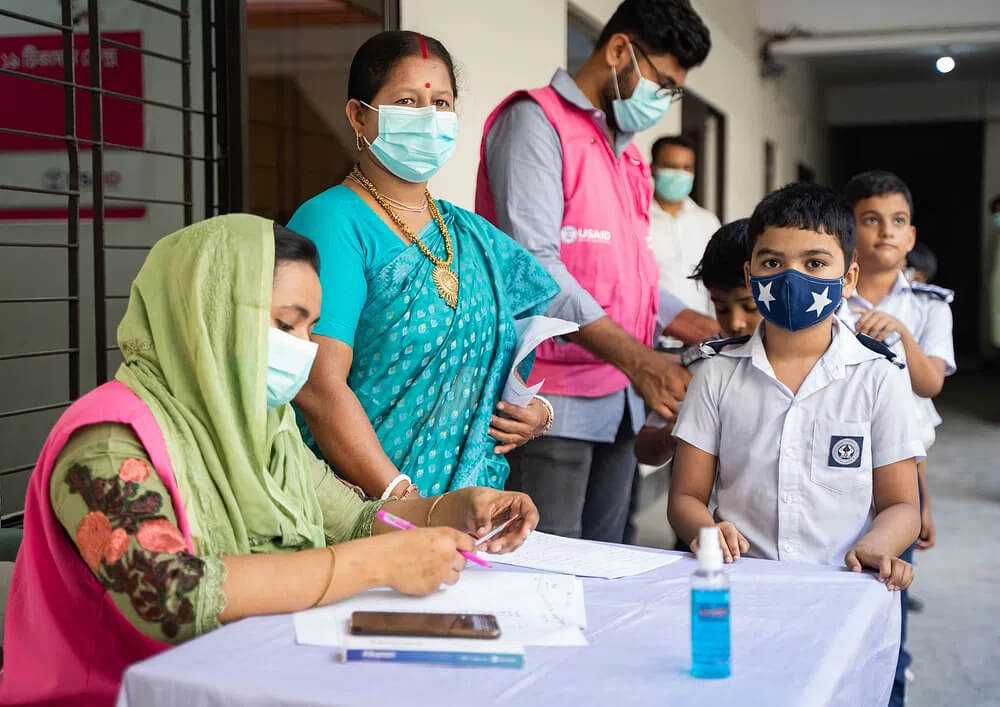

Photo: Rawpixel

This was called the Mumbai Model. Because we don’t normally have all this, it seemed great but why has it stopped after COVID? On a relative scale, Mumbai’s public hospitals seem better equipped, more efficient, and offer more complex care. But compared to what, Uttar Pradesh? That’s no comparison. Compared to Kerala and Tamil Nadu, Mumbai or Maharashtra are not doing that great. Mumbai is a megapolis, a city of wealth but also social consciousness. It can do better.

How can the public healthcare system be made more accessible to more people, especially the marginalised? Who should take responsibility?

These are essentially questions of class and political economy. Hospitals are better when people demand better healthcare and put pressure on elected representatives. Does it work, do politicians win elections on better health care? I don’t think so. Did parties win on the Ladki Bahin scheme? Maybe, they did. So, as an electoral issue, healthcare is still not up there unlike many countries, the UK definitely, where elections are won or lost on health care. How to change this is one of the questions.

I am sorry to say the obvious but if we want a better life we have to ask for it, push and advocate for it, organise for it. The elite, that includes you and me, have seceded from public hospitals. The influential don’t access them. During COVID, I helped people get hospital beds but hardly anyone preferred public hospitals. Common people will realise they are being denied basic healthcare and push back. People don’t do that as much as needed, partly because of the daily challenges of a hard life, the myriad distractions of identity and religion, but the consciousness about healthcare rights also does not exist. In Kerala, that consciousness exists, so the healthcare system is better.

You said healthcare should be the state’s intervention. What do you recommend as action points?

The obvious one is healthcare spending and infrastructure. Then, the system must be decentralised to form a network. For example, if I have a patient needing dialysis in Bhabha, a peripheral hospital, the patient cannot be put into an ambulance and taken around the city from KEM to Nair to Sion hospitals because no one has beds. There has to be coordination between different levels of hospitals in the system. This, called the triage, was done during COVID but is needed in normal times. It cannot be left to people’s fate and luck.

In an accident, which hospital you will be in, what facilities it has, is all luck. In most large global cities, there will be an organised ambulance system taking you to the nearest hospital and all hospitals have minimum standards. I worked in London and saw the system up close. Here, a citizen is a dead duck if you are far from a decent facility or don’t reach one in time. The Mumbai Model of COVID is needed permanently for all illnesses. This is wishful thinking but what’s the harm in being optimistic?

Cover photo: Wikimedia Commons