We watched romance brewing between Amol Palekar and Vidya Sinha as they waited at bus stops and took the BEST bus to work in Chhoti si baat (1975). The entire song Jaanu meri jaan from the film Shaan (1980) was shot on a double-decker BEST bus with Amitabh Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor wooing their lady loves Parveen Babi and Bindiya Goswami. BEST did not just play cupid. It was also a protagonist in the scene between cop Akshay Kumar and offender Suniel Shetty in the film Mohra (1994). In Shootout at Wadala (2013), John Abraham makes his entry in the middle of a fight, in what else, but the BEST bus.

On reel as much as on the roads of Mumbai, the Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST) bus has been immortalised. Seeing it on the screen has meant familiarity and joy. Sighting it on roads is a source of comfort for millions in Mumbai. What if the iconic BEST were to have its own museum recounting its journey from the era of horse-drawn trams to the air-conditioned electric buses we see today? As it happens, there is such a museum though it hardly registers on people’s sight-seeing plans.

Tucked away on the third floor of the administrative building of the Anik bus depot in Sion, it is easily missed even by veteran Mumbaikars. The taxi driver who drove me here did not even believe there was a museum for the city’s transport and electricity provider. At the depot, bus conductors directed me to the famous Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Fort before remembering that the bus service had a museum on the third floor in the building.

It is ironic that this museum, displaying the ubiquitous buses, is virtually absent in the city’s popular imagination. The BEST story began back in 1873 as the Bombay Tramway Company Limited with horse-drawn trams, morphed into the Bombay Electric Supply and Tramways Company which spearheaded electric trams in 1907 and followed these with double-decker trams a decade later before beginning the bus service in July 1926.

The narrative has stories about these organisations, the passage of time and types of buses, the routes charted into the newly expanding Bombay, the urban geographies it connected and the people who made it the city’s pride, drivers and conductors who once commanded immense respect among Mumbaikars. A well-curated museum is a significant historical documentation but, more than that, it is a virtual memoir of the city itself.

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

The BEST Museum

Set up in the Kurla bus depot in 1984 by BEST officer PD Paranjpe, the BEST Museum was shifted to its present location in 1993. Anik Depot in Sion East, off the Eastern Freeway, can be a tad difficult to reach.

The Museum has a wide array of material on display though in conventional museum style. Posters in Marathi trace the journey of the organisation and recounts stories such as how the Ganesh idol christened ‘BESTcha Siddhivinayak’ was gifted by Deputy General Manager CD Jeffries when it became a subsidiary of the BMC or how the earliest trams ferried commuters for free so to get people to accept it or how an ‘Ordinary Share Ticket’ for six shares worth Rs 50 each from the 1900s shows that the Bombay Electric Supply and Tramways Company Limited was listed on the stock market.

The tram tickets worth one anna (5 paise in the current Indian rupee system) had route maps from Sassoon Docks to Dadar through Pydhonie, Nall Bazar, Two Tanks, Parsi Statue, Victoria Gardens – geographies we speak about and live in even today. On display are also old seats, bus engines, and ancient signals. What also catches the eye are miniatures of the horse-drawn tram, the electric tram, the bus, the various BEST bus stops that exist across the city, of entire depots, even a miniature of the proposed BEST museum in Rani Bagh in Byculla that was not given permission to build.

Pune residents Pradnya Naik, 39, and her 11-year-old son Vivan, a motor vehicles enthusiast, take delight in each exhibit. “Mumbai has a great public transport system, especially in comparison to Pune. I am happy to be able to show my son what that looks like in a city,” says Naik, who grew up in Mumbai using public transport.

The vanishing BEST bus

The first BEST bus ran on May 9, 1874, but the museum has objects older than that like the 250-year-old fan, the grandmother’s clock, and also the dome-shaped junction traffic assistant that flashes various colours at intervals. Yatin Pimpale, assistant foreman at the museum, says, “There are plans to expand the museum, to pay homage to the retired iconic double-decker buses as an interactive installation.” The trailer double-decker buses, once a novelty, were withdrawn from service in 2023.

Though the Museum generates low public interest, schools have been bringing their students here. “The model of the BEST bus is quite popular among students. It gives them, who have never taken the bus in their life, the experience of sitting in one,” says Ambadas Garje, the clerk. Much like the Museum not easily noticeable, the BEST buses too are fading from the cityscape. Their number has shrunk from 4,200 to barely 2,670; of these, only about 700 are owned by the BEST, its lowest ever; most are on wet lease from private contractors.[1]

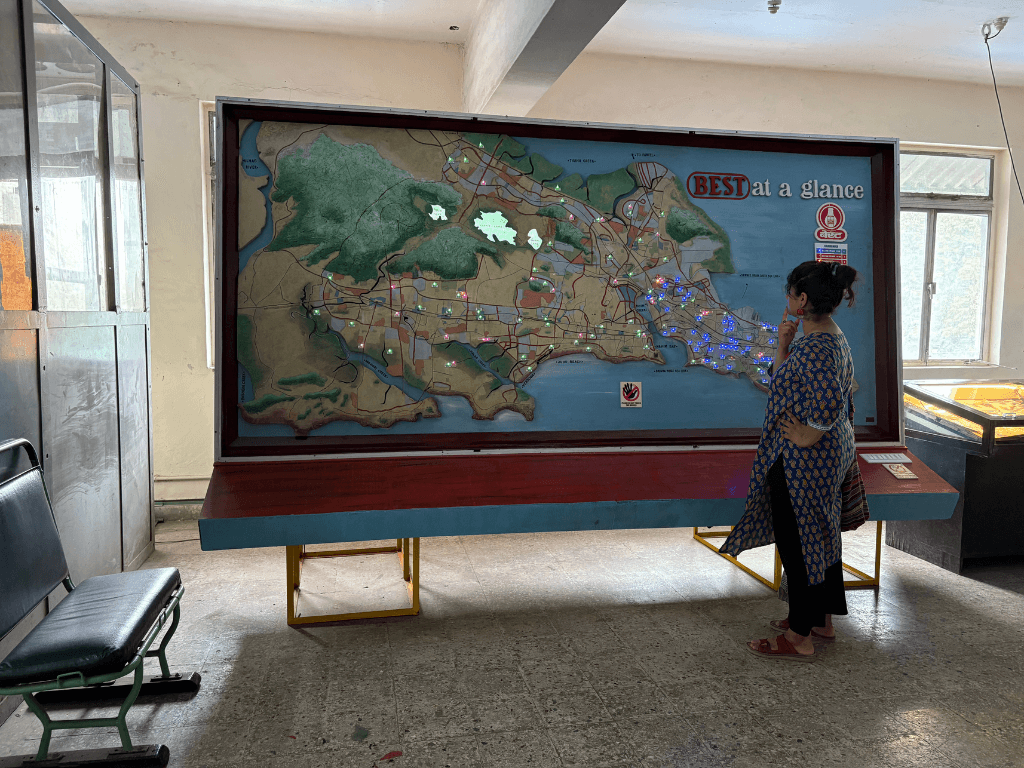

In the Museum, a map of the 26-27 BEST bus depots dotting the city brings out how the service connected the growing city and its train system – a stark contrast with the metro network that’s all over but functions quite like an island on its own. That the BEST has total losses of nearly Rs 9,300 crore and lacks funds is no secret; a museum is hardly a matter of priority in these circumstances. Citizens’ groups have been rallying to save the BEST by ending the wet lease model which has benefited the contractors but drained the BEST besides providing declining services.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Bollywood reels as archive

Regardless of the location and depth in the Museum, the BEST bus has a living archive in Bollywood movies. From romance flicks to action films, the movies are a gallery – for a chase in Aamir (2008), to bring in young love between Dharavi’s slum dwellers in Gully Boy (2019), to show tension between lovers in Saathiya (2002) and OK Kanmani (2014), in chase sequences, in shootouts, to depict the raw edges of life in Mumbai.

As the mainstream films moved away from the grit and grime of life-inspired stories to candy floss ones, the BEST bus showed up less and less on the screen. Even so, the movies remain its enduring archive. The romance of taking bus rides is, indeed, now more on the screen than in the real world given the long wait times, poorly-equipped bus stops, dust and pollution on the rides, rides that seem to take forever due to the traffic congestion.

For many upwardly mobile Mumbaikars, BEST bus travel may be a fond memory but not an efficient option any more. For the 3.3 million Mumbaikars who depend on it even today, the BEST bus is a lifeline to work, study, and recreation. For a few, prints of the BEST bus are frames hanging on their walls as an emblem of the city.

Films, both non-fiction and fiction, are archives of the urban space. The importance of the moving images is being recognised by archivists, museum curators, and researchers. “…the finished productions stand as archival manifestations of their own making, not simply in terms of the documentation of people and places at specific points in time. The films become imagistic and conceptual archives of not only the city at the point of production, but of their own making within the nexus of cinematic, popular cultural and national history,” wrote researcher Jonathan Rayner at the University of Sheffield about international cinema.[2] It holds true for Bollywood films too.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

“Films have always celebrated the space of the encounter between strangers,” says architect, urban designer and filmmaker Rohan Shivkumar. “In Mumbai, it’s public transportation infrastructure like BEST buses and bus stops are spaces where one can meet a future friend or lover, as in Choti si Baat, Naach or Gully Boy; or even a space where you may experience a moment of struggle or violence, as in Ardh Satya.” These moments capture the essence of what it means to live in a city, its thrills and excitements, spaces beyond the boundaries of caste and religion, he adds.

Shivkumar cites Richard Sennet’s argument in the book The Uses of Disorder, “Without these moments enrich the urban experience, without the ability to be able to engage with the other we would never be able to evolve- or grow.” As the city and its transportation systems are gentrified, these moments become more difficult.

Why have transport museums?

Museums in cities about housing, transport, work and people’s lives beyond the ones on art and history, offer the most over-arching narrative of the cities – how they came to be, who made them into pulsating centres of economics and culture, which industries underwrote their importance, how people lived and worked, how they played and made merry, and, of course, how they moved within the cities given how critical commutes have been to modern cities.

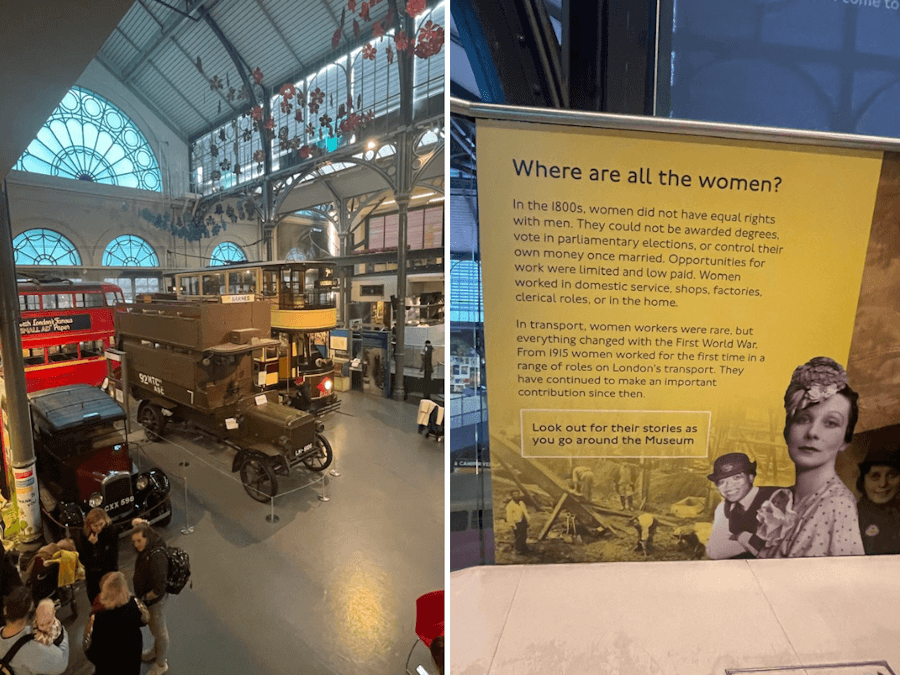

Some of the most popular transport systems of the world have their museums showing how affordable and reliable bus transport has been an intrinsic part of urban development, not a luxury. The London Transport Museum has, besides a breath-taking narrative of history from trams to the tube and buses, regular retrospectives, old buses as exhibits, people’s struggles as panels. Japan’s Kyoto Railway Museum boasts 54 retired trains and train cars.[3] The Transport Museum Remise in Vienna displays public transportation beginning from horse-drawn trams to modern means of transport.

Photos: QoC File

In every case, the museum is a journey of that city, a memoir, a record-keeping place, a tracing of the evolving transport system. The need for public transport museums is at least as important as the need for public transport itself – not merely to trace the history but to remember that the evolution of public transport was the result of deliberate decisions and policies at every step, a part of political decision-making. Besides, they tell us so much about the daily lives of people in different eras.

The BEST’s robust connectivity across Mumbai did not happen accidentally. As the city expanded, developing northwards into far suburbs, the bus network kept pace too. This meant that the first tram ran between Pydhonie and Colaba but about a century later, the BEST ran routes from the southern tip of Navy Nagar to Borivali some 40 kilometres away and connected Borivali to Vashi in Navi Mumbai across the harbour. And at affordable rates so that the common folk did not feel the pinch.

All this is necessary information to be archived for later generations of Mumbaikars as BEST services shrink. At the Museum, we realise that the first tram services were free of cost, that the tickets mentioned its stops too, that the service offered longer duration tickets for Jews on Sabbath so they would not have to exchange money and so on.

Transport museums help relate today’s questions of mobility to the historical developments of the past, writes Swiss historian and museologist Kilian T Ellasasser in a paper on transport museums. “The role of the museum is not about giving answers about the future but, through telling stories about the past, inspiring how future developments can be shaped.”[4] Bollywood films may immortalise the BEST bus and show us its many facets, but for the city of Mumbai, a vibrant and accessible museum would be more fitting.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey