On October 8 this year, acclaimed artist Noni Borpuzari had a distressing morning when floodwater invaded his Guwahati home, damaging a number of his valuable paintings. It was an unprecedented experience for the artist in a city that has seen floods over the past 50 years.

The septuagenarian resident of Zoo Tiniali area recalls battling against rain water when he lived in his ancestral house which had to be demolished about 15 years ago when the flood waters entered the houses through the windows. A new building was constructed for which the plinth was raised by about 6 feet, making it the highest in the neighbourhood. Despite that, there was about 1-foot water inside Borpuzari’s house this year. His neighbours, who had not raised the plinth of their homes, suffered more.

For days this October, Guwahati witnessed intense and consecutive days of rain. Recognising a noticeable shift in Guwahati’s rainfall pattern, Borpuzari believed that the state government must focus on the drainage network.

“Zoo Road gets flooded when the water flows back from the drains in Nabin Nagar during heavy rain. I doubt if there has ever been any proper study and planned drainage in Guwahati. Building individual drains will not suffice to prevent the city’s flood; comprehensive drainage planning is a must,” he added. This is echoed by several others in the city.

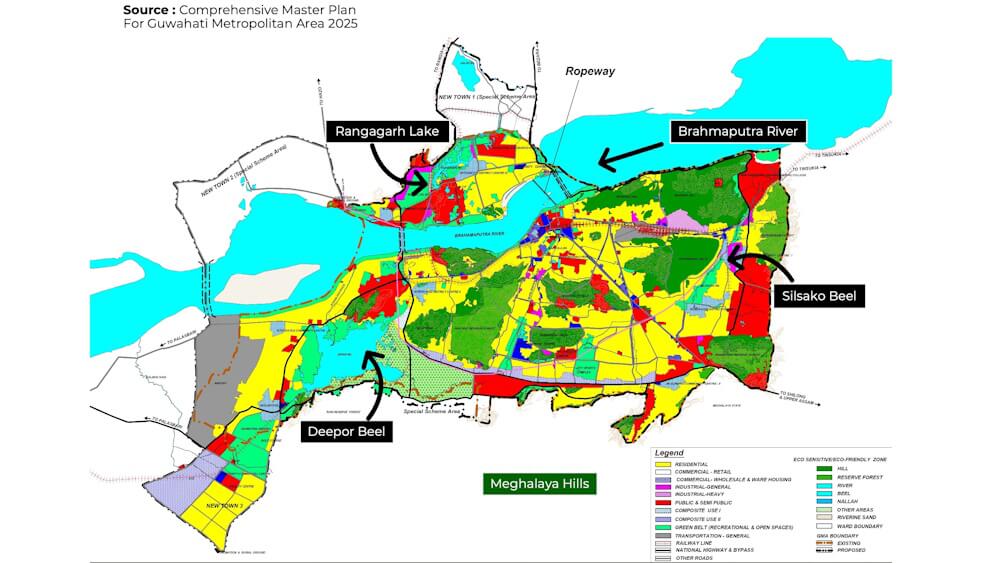

As Padmashree awardee Ajoy Kumar Dutta, former councillor of the Guwahati Municipal Corporation’s first wards committee in 1974, explained, Guwahati is surrounded by 18 hills and had a significant expanse of water bodies which were interconnected and linked to the Brahmaputra River, thus forming a natural drainage system.

However, “the alteration in land use started in the 1960s,” he stated, adding, “As the inaugural ward committee, we pushed for a comprehensive underground stormwater drainage and sewage network spanning the entirety of the city.” Despite funds allocated from the World Bank for this project and a ‘contour survey’ of the city in the 1970s, these remain incomplete.

Changing rainfall pattern

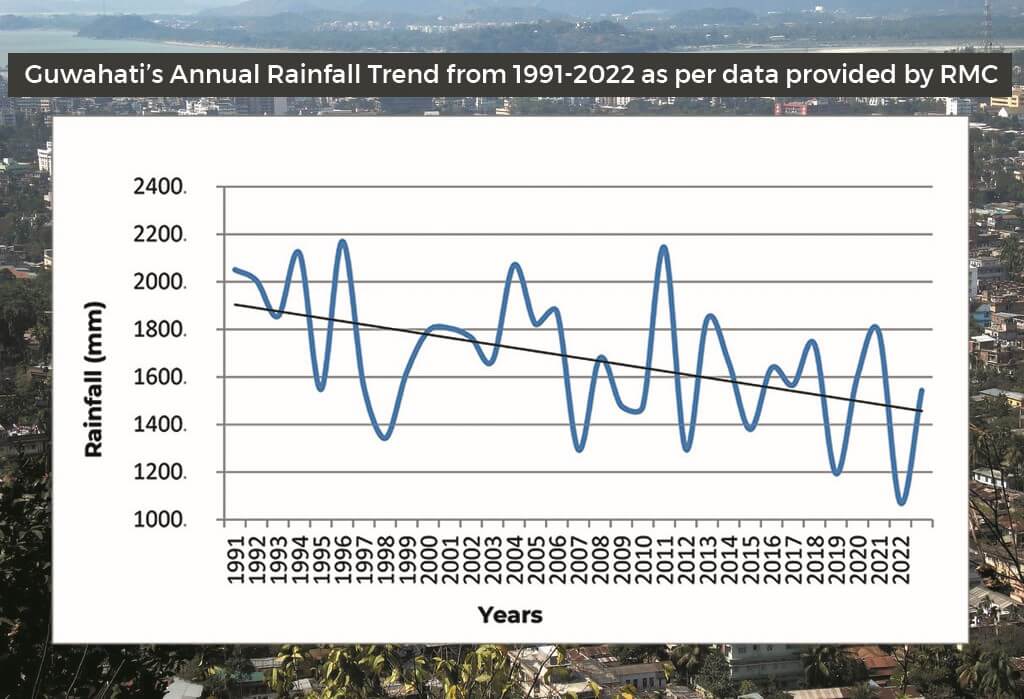

Over the past few decades, the city has witnessed a change in the rainfall pattern. The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), analysing the data from 1982 to 2011,[1] observed that “although there has been a decreasing trend in the overall seasonal rainfall as compared to the long-term average, there has also been an increase in extreme rainfall events resulting in more rainfall in short duration.” The Regional Meteorological Centre (RMC)’s rainfall data between 1991 and 2022 supports this.

This year, though the RMC declared that the monsoon had ended on September 30, Guwahati experienced unprecedented heavy rainfall on October 1, 5, and 6. This tested the administration’s preparedness for such intense precipitation. It caused drains to overflow including the Bharalu River which flows through the city and could not discharge water into the Brahmaputra where the flood level was already high.

The water from Zoo Road and nearby areas flows through the secondary drain of Nabin Nagar to Anil Nagar, about two kilometres away. This water has to be pumped out to the Bharalu. However, due to the already elevated water levels in the Bharalu, authorities could not pump out the excess water which meant it flowed back, resulting in the flood of Borpuzari’s house two days later.

The urban sprawl

Guwahati’s present issues with flooding lie in its past approach to the built environment. This has become urgent as climate change impacts make the city more flood-prone.

Assam is the most vulnerable state in India to climate change, found the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) in its national Climate Vulnerability Index.[2] The report confirms the landscape disruption – largely human-induced – which appears to have spurted the frequency and intensity of hydro-met events or floods in the case of Assam. The report found that 54 percent of all flood hotspot districts in India saw significant land use and land cover (LULC) changes between 2005 and 2019.

Guwahati is trough-shaped and built on a landscape featuring a mix of plains, water bodies, marshes, and hills. The city experienced high growth in the post-independence decades; its population surged from approximately 44,000 in 1951 to 9,57,352 in 2011, or nearly 21 times.

This is attributed largely to the influx from Bangladesh in the 1950s and, later, the shift of state capital from Shillong to Dispur in Guwahati in 1972. The city’s area expanded from a mere 7.86 square kilometres in 1951 to 216.09 square kilometres in 1974 — nearly 26.5 times — when it attained Municipal Corporation status. This urban sprawl currently covers 328 square kilometres.

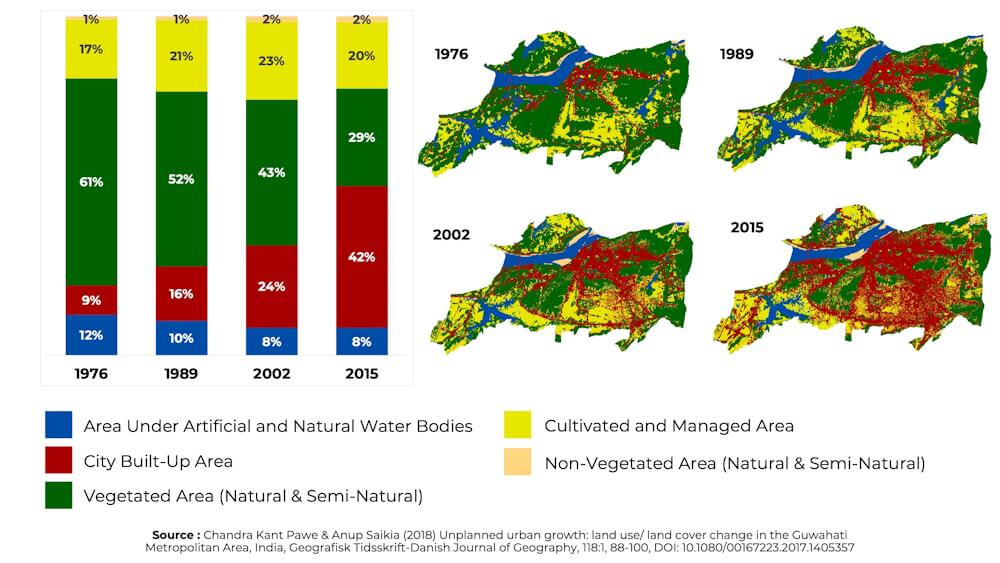

It extracted a price. The data shows a decrease in vegetation area from 61 percent to 28.7 percent and in water bodies from 11.9 percent to 8.1percent between 1976 and 2015, as the built-up area steadily increased, encroaching even reserved forests and demarcated hills areas.[3]

Guwahati has had several Master Plans since the 1960s. However, except for the 17 kilometres of drains built between 1973 and 1997, no other extensive and planned drainage network exists in the Guwahati Metropolitan Area (GMA).[4]

Without this, the existing drains are burdened twice over – channelling the grey water from the residential, commercial, and industrial areas in normal time and also discharging the excess rain water during rainfall.

The Master Plan 2025,[5] published in 2009, recognises Guwahati’s drainage issues. There has been some effort made in the past few years to mitigate urban floods. In July 2022, the Guwahati Development Department initiated ‘Mission Flood Free’ which was a collaborative effort to de-silt rivers, maintain feeder drains, construct new drains, enhance road infrastructure, and enforce rainwater management structures in line with the building bye-laws. The Mission involves agencies like the Guwahati Metropolitan Development Authority (GMDA), Guwahati Municipal Corporation (GMC), Public Works Department (PWD), and the Water Resources Department (WRD), each assigned with specific responsibilities.

Yet, without a comprehensive effective drainage plan, the existing deplorable situation will only worsen, exacerbated by the rising frequency of extreme weather events due to climate change, as observed in October this year. Heavy rains battered the city in the first week of October, creating a flood-like situation. Guwahati is clearly not climate-resilient.

Overburdened drainage system

There are glaring challenges and problems in all facets of Guwahati’s drainage system, most of them significantly attributable to human activities.

Alongside the vast changes in land use, the thatched roofs and soil surfaces of the older era were replaced with concrete roofs and concrete, bitumen or asphalt-based roads. With diminishing permeable surfaces for water to percolate into underground reservoirs, the rain falling on the hard urban-city-surface all flows into the drains burdening them beyond capacity.

Additionally, the deforestation and encroachment on surrounding hill slopes have accelerated the volume and flow of rainwater reaching the city drains. As a result, erosion and mudslides happen frequently. Large quantities of these enter drains, and clog them. This is true for three of the six primary drains in Guwahati, namely the Bharalu-Bahini River, Basistha River and Mora Bharalu River.

These water bodies along with the other three primary drains of Bondajan, Khanajan, and Ghorajan, and major wetlands like the Silsako Beel, Deepor Beel, and Rangagarh lake, have also shrunk due to encroachments, natural siltation, earth filling, growth of vegetation and hyacinth, and dumping of solid waste. Their water retention capacity has substantially diminished over the years.

Also, unlined drains, irregular sections due to soil erosion, and their intersection with service pipelines and low bridges or culverts prevents the swift flow of excess floodwater out of the city. Additionally, a number of secondary drains are discontinuous, have reduced sections at the inlet and outfall points, and not maintained.

As a cumulative result, Guwahati’s drainage system, which was not designed to carry a high volume of water, becomes overwhelmed with water from several sources within hours of heavy precipitation.

The continuous elevation of road and house plinths coupled with simultaneous levelling of areas has reduced the slope gradient of drains, thus necessitating the use of mechanical support like pumps and sluice gates.

Professor Rajib Kumar Bhattacharjya at IIT-Guwahati’s Civil Engineering Department, an expert in flood and drainage modelling, said, “Raising the road levels to prevent flood in a locality is a very localised solution. If not planned well, it can create undulation of the original catchment slope creating new flood-prone sunken patches within the cityscape. Besides, efforts must be made to implement the concept of zero discharge, which will reduce the surface runoff, to improve the functioning of the city drainage system.”

Photo: Surajit Sharma

Climate-proofing Guwahati’s drains

A way to enhance the efficiency of the existing drainage system involves the implementation of Sustainable Drainage System (SuDS) tactics. These focus on the controlled release of surface water into the drains by managing rainfall close to its source, promoting infiltration, and facilitating storage. This helps to drain rainwater in manageable batches, without overwhelming the system.

For this, Guwahati requires an increase in permeable surfaces. Roads should be constructed with permeable materials that allow the water to infiltrate into the groundwater aquifers; property owners should be encouraged to install green roofs, rainwater harvesting tanks, and on-site attenuation tanks, measures which can effectively mitigate the immediate runoff of rainwater into the drains. While Guwahati’s building bye-laws mention rainwater harvesting, the implementation has been minimal.

Over the years, several studies have been conducted by government departments and academics to examine the causes of urban flood and mitigation measures. Amongst them, a report prepared by Tahal Consulting Engineers Ltd. for the GMDA in 2008 offers a contour survey and comprehensive examination of every primary, secondary, and tertiary drain in the city, along with detailed recommendations to mitigate the risk of flooding. The Master Plan for GMA– 2025, published in 2009, largely adopts these recommendations. Also, the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA)’s Report of 2014 compiles the findings and recommendations of all previous studies on flash floods.

The recommendations underscore the imperative to curb unplanned deforestation along with the prevention of encroachment on hillslopes. The proposals include the installation of silt traps or grit chambers where hill run-off enters the drainage system in the plains; skimming platforms on almost all primary drains at every junction of internal roads and major drains.

Regular cleaning and maintenance are non-negotiable. The re-sectioning of major drains has been recommended as also the construction of sluice gates and pumping stations at outfall points. Additionally, areas which are not well connected to the primary drains need an interconnected tertiary drainage network.

The surviving wetlands, especially the Silsako and Deepor Beel, need to be proactively maintained for which the effective implementation of the Guwahati Water Bodies (Preservation & Conservation) Act is imperative.

Photo: Promod Kalita

Mission Flood Free

Over the years, the GMDA has undertaken projects including the development of Silsako Beel to increase its stormwater retention capacity, dredging for de-siltation and cleaning of drains including Bondajan, Pamohi channel, Borsola Beel, and NH-37. Similar efforts by the PWD showed encouraging results, guard walls of the Bharalu River were raised at several points.

Under Mission Flood Free, the PWD undertook nine construction activities ranging from a RCC bridge, re-construction and upgradation of drains and roads, slab culverts and outlet load drains. However, these projects were aimed at mitigating floods in specific localities and were often initiated without factoring rainfall uncertainties due to climate change, relying on traditional rainfall data and recommendations from locals and officials.

GMC Commissioner Megh Nidhi Dahal said, “Last year, five primary drainage channels — Bahini, Bharalu, Mora Bharalu, Lakhimijan and Basistha – and 143 drains were desilted and cleaned. Ideally, the cleaning is done between December and April, especially in a handful of crucial areas. Silt or grip traps are cleaned before the monsoon. Several low-cost temporary floating barriers were installed on the Bahini and Bharalu rivers to trap solid wastes this year.”

The GMC also undertook several evictions on the Bharalu and Bahini rivers and demolished or rectified 26 bridges on the latter to facilitate de-siltation. Silsako also saw similar actions. Six permanent pumping stations and six additional stations with mobile dewatering pumps functioned this monsoon alongside the sluice gates to tackle the floods.

While these were effective locally, they do not replace the much-needed comprehensive city-wide flood planning. Sanjiv Shyam, chief engineer of the state PWD (roads) stated, “The Tahal Report is the most comprehensive one on Guwahati’s drainage and sewage network. Proper implementation of 70 percent of its recommendations would prevent the flood to a large extent.”

Shyam emphasised the need for a dedicated stormwater and sewage network, and also a separate department or a specialised wing within the PWD to manage the extensive task.

Recorded data around extreme rainfall events, possible shifting monsoons, and high vulnerability to climate change-related flood risk makes a strong case for deploying a comprehensive city-wide stormwater drainage strategy. This must also ensure the smart use of the existing drainage network through the Sustainable Drainage (SuDS) Mechanism to ensure optimal capacity around the year, even beyond the official monsoon period, to minimise floods in Guwahati.

Barasha Das is an independent journalist based out of Guwahati, Assam. She reports on environment and Climate Change — causes, adverse impacts, and policies to combat climate disasters. She has extensively covered every aspect of reporting on ‘city’. She is also associated as a Research Writer with OnePointFive Tribe, a platform working for a Net-Zero Carbon Future.

Harish Borah is a subject expert in cost/carbon studies within the building industry. He is the Principal ‘Carbon’ Expert for ADW Developments (UK); member of GRIHA’s ‘Technical Advisor Committee’, and Founder of OnePointFive Tribe. His work portfolio is spread across the UK/EU, the Middle East, and India. He has also been named among India’s top 25 leading minds in sustainability by the Economic Times.

This is the second part of a series supported by the QoC-CANSA Fellowship to report on Climate Change and cities in four nations of South Asia. The first part can be read here.

Cover photo: Waterlogging in Hatigaon area in Guwahati in 2021. Credit: Surajit Sharma