A friend and I recently travelled from Thane to Bandra by Mumbai’s suburban trains to meet our group. This was a casual and informal day out with friends but we both caught ourselves calculating each minute of our movements. In fact, our string of decisions began with the clothes we would or should wear, the time we should return before it became ‘unsafe’, the rush hour to avoid to dodge unwanted touch of men, the railway bridges to take to avoid being sandwiched between men and their suggestive eyes, the safest exit at Bandra station, the streets to avoid, whether we should stop for tea. Phew, it ended when we had finally reached our destination.

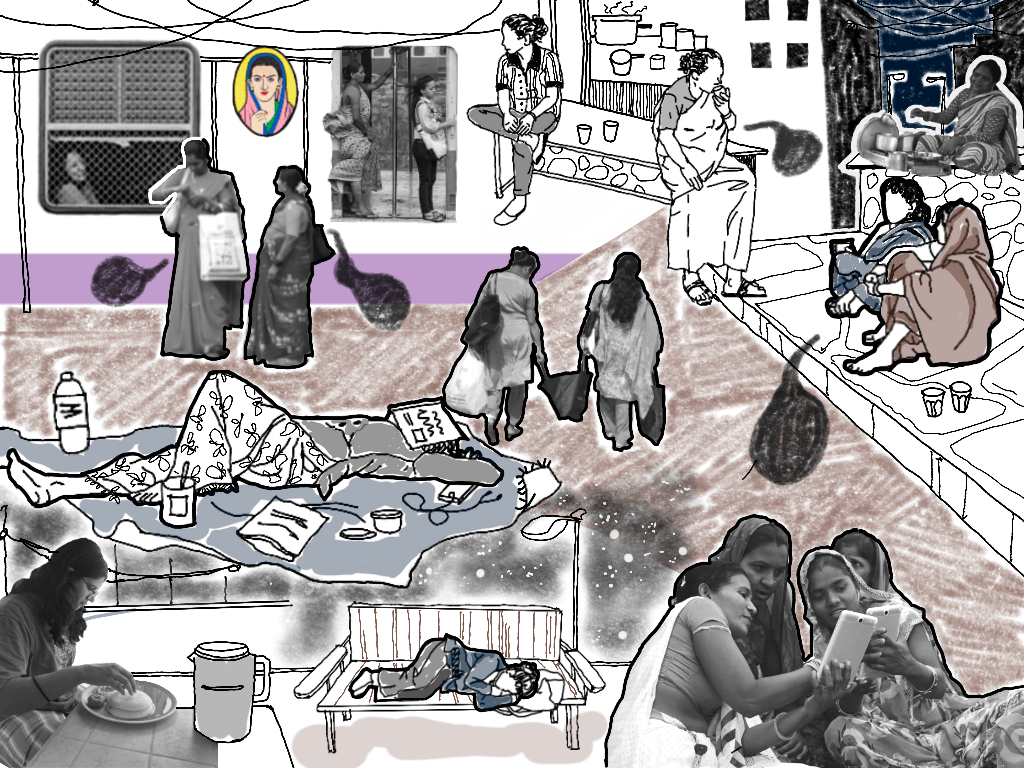

We are not alone in this. Women micro-plan like this all the time to be safe. It has been normalised and it really exhausts us. We become so accustomed to such calculations that they do not seem absurd anymore. It is our amalgamated response to all the times we had to push ourselves into a crowded bus and were elbowed by opportune men, or simply stared at, when we sat in shared autorickshaws and shrunk ourselves wishing a protective shell would magically appear around us, when we struggled into a densely-packed ladies compartment and realised that the romanticised ‘spirit of Mumbai’ is a cover for safety hazards.[1]

Many of these got imprinted on our brain as we grew up – some experienced in our growing-up years, some told to us, others as vivid images of stories heard. Memories become so etched that we can recall every detail years after an incident. We remember the clothes we wore, the colour of the walls, the people we met, the food we ate – and the sexual violation incident that we want to forget. It sends us right back to feelings we felt then, of shame and fear.

Why do we remember? “The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) which we do not suspect,” wrote Marcel Proust in Remembrance of Things Past.[2] So, if my mother recalls the railway station she was at 30 years ago where she had to threaten her harasser with an umbrella or my friend remembers the lane she was walking in and the clothes she was wearing ten years ago when sexually harassed, it is because these incidents are etched in their memories, dictating so many decisions in later life.

Our survival mechanism is to micro-plan so that we can avoid making more such memories – as if it was in our hands.

Subtle acts of shielding the body

I do not mean to devalue the experiences of other genders, including men, in public spaces but carrying my body around like an object that has to be safeguarded feels absurd. It is only my body, after all. Why should I feel threatened? But the audacity of my body to feel unfamiliar, like someone else’s, makes me want to peel it off and throw it away. It is exhausting even to fathom the reason behind such feelings. Yes, I know that, historically, women’s bodies have been the sites of men demonstrating their power on women, also to other men. But how do I shield my body? Why should I?

I recall a conversation with a friend a few months into the Covid-19 lockdown. Both of us expressed how this threatening virus, ironically, enabled us to be safe in public places because distance had to be maintained. We walked instead of slithering and dodging a crowd, trying not to bump into men who refused to move aside. Did it have to take a life-threatening virus to keep casual elbowing, brushing, touching and male obstinacy at bay? I am certain we were not the only women who heaved sighs of relief then.

Here it is. Even our walk changes course in public spaces only because we feel threatened by unwanted, lewd, sexual public gestures. We learn to move out of men’s way and, of course, shield our bodies.

Travelling comfortably late night

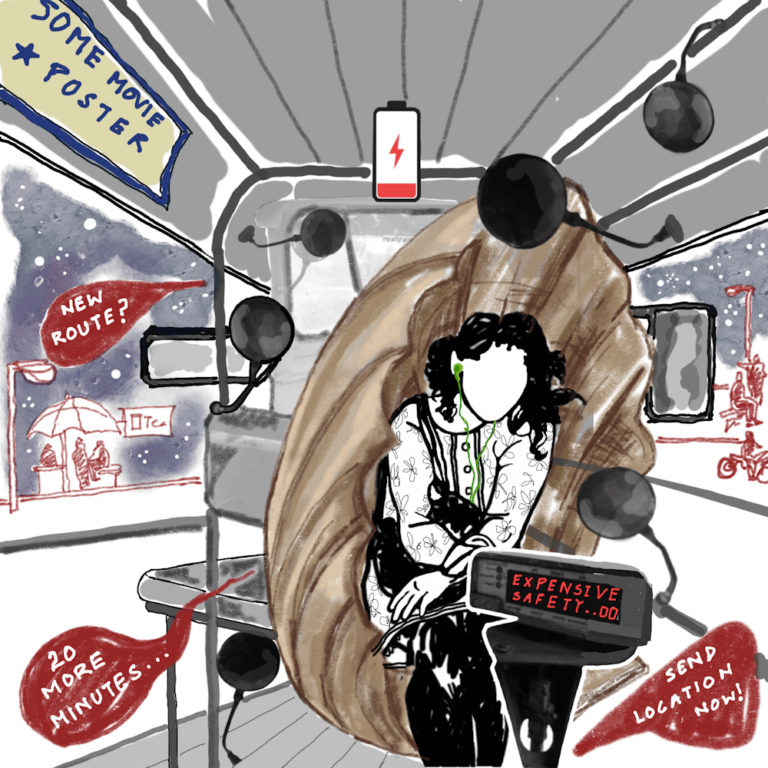

Every time I return home late at night, my first act, without deliberate thought, is to share my live location on at least three individual chats and two group chats of people in the city. This is to remain safe, metaphorically get insurance against an ‘untoward incident’. Recently, I was going home around midnight in an autorickshaw with a male friend who was to get off about 40 minutes before my house. We were sleepy and exhausted, but as soon as he alighted, I turned down the volume of the music I was listening to, sat up straighter, and suddenly became highly alert despite the drowsiness.

The liberty to unwind during a ride at the end of a long day is not for us women. I cannot lower my guard till I step into my house. Noting minute details of each action of the driver requires as much focus as my day job, or maybe more. That night, as the rickshaw hit the highway, I saw men in pairs and groups chilling, talking, laughing, or alone riding their bikes. I was overcome by envy and irritation. This inner push towards a constant thought process of the possibilities of sexual violence, things I should not have to think about and whose occurrences are not even in my control, has driven me into a state of clinical anxiety.

“…Imagine women in saris, jeans, salwars and skirts sitting at the nukkad reflecting on world politics and dissecting the rising Sensex. If you can imagine this, you’re imagining a radically different city…It’s different because women don’t loiter. Men hanging out are a familiar sight in the city. A man may stop for a cigarette at a paanwalla or lounge on a park bench. He may stop to stare at the sea or drink cutting chai at a tea stall. He might even wander the streets late into the night. Women may not. We argue that there’s an unspoken assumption that a loitering woman is up to no good. She is either mad or bad or dangerous to society,” wrote authors Shilpa Phadke, Sameera Khan and Shilpa Ranade in Why Loiter? : Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets.[3]

My anxiety is not because I am loitering. It is second nature even when I am purposefully going from one location to another. It is simply the possibility of sexual violence.

My stolen time

My concerns and questions are not new but if I zoom in, or scale down, the questions from the large frameworks of policy, justice and legality, they are about time. My time, taken away in anxiety, in preparation against impending violence, in outrage against acts of transgression and violence against other women, in disgust at men. An easy way to reduce someone’s capabilities is to deny them their time, steal it, take it away in unproductive thought.

I feel more outraged about my stolen time. The cumulative time I have spent in my young life calculating and exercising my safety protocols is time I could have spent finishing some work, done an additional course, enjoyed the night a little longer, walked more with a friend. Rarely do women think about their time stolen this way by social norms that somehow normalise sexual violence or sexual threats but it is, indeed, our loss.

Conditioning in home and schools

The normalised over-thinking is cemented in homes, schools and other institutions. The subtle administration of sexist norms means, as young girls, we are ‘disciplined’ into not laughing too loudly, always double-checking our clothes, and being aware of fitting into the cookie-cutter of societal behavioural norms.

Our homes and schools impart lessons not only in academic subjects but also policing our language, shrinking our bodies, distorting histories, injecting casteist notions of purity, inculcating false power dynamics, and most of all lovelessness. I remember the words of Bell Hooks in All About Love: “All too often women believe it is a sign of commitment, an expression of love, to endure unkindness or cruelty, to forgive and forget. In actuality, when we love rightly we know that the healthy, loving response to cruelty and abuse is putting ourselves out of harm’s way.”[4]

I remember loving school when I was still a student but, as I returned to it in memory, I realised that much of what was hammered into us were distorted ideas of respect and civility. Teachers would make us stand in a queue during the morning assembly and check how our hair was tied, the length of our skirts and socks, our nails and the absence of nail polish, our proximity with fellow students (especially male), and it always ended with some student humiliated in front of the whole school. A friend of mine was once sent back home on her birthday because her dress was “too short”. She returned wearing “appropriate” clothes but had missed classes.

This system of using shame to discipline young girls instils not love or respect but fear and a feeling of lack. It leaves deep impressions that these behaviours are ‘socially unacceptable’ and ‘punishable’. When we are asked to show respect to the teachers we feared, we start equating fear with respect. The pattern continues at home, in workplaces, in romantic relationships, and in choosing our political leaders.

During festivals like Holi and Diwali, before schools closed for a break, students would carry water balloons, colours, and small crackers to celebrate after classes. Teachers would check our bags and pockets for where we could have hidden them. When girl students were found with these, their comments were “Why are you carrying these even though you are a girl?” and “Girls shouldn’t behave this way, it is expected from boys” and would end in our ID cards or books being confiscated. This, I realise now, was also a way of taking away our time. Time in which we could have imagined and dreamt differently as young girls.

From schools to homes. Young boys start treating their sisters through the same frameworks of disrespect and control. They cultivate a sense of entitlement, feel the need to be apologised to for imagined hurts or unconsidered opinions, or if their female friendships don’t live up to their expectations. These expectations stem from a distinct patriarchal Brahminical upbringing, where there is a need to be served, where men don’t enter the kitchen and elders are to be respected no matter what.

I know of ‘liberal’ homes where subtle distinctions exist in the way a son and daughter are raised. And daughters are told that it is for their safety. These distinctions are both microcosms of the world outside and reinforce the sexism in public spaces. In my home, we were always given a framework to be within which had little room for mistakes but had the fear of failure. I often struggle to put things together effectively, to make frameworks of my own without feeling the guilt of betrayal.

If sexual violence, or something ‘untoward’, were to happen to me, I might feel as if I was ignorant or careless about being in the public. I would then carry guilt besides the shame and fear of being scrutinised and attacked as a woman. How do I occupy my own space, how do I claim my space in the world not made by women, for women?

Nikeita Saraf a Thane-based architect, illustrator and urban practitioner, is now with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from the need to understand people and the methods with which they map the world. Through her everyday practice of illustrating and archiving she intends to explore this further.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf