After a start-up phase of several centuries, the world system is increasingly stabilizing itself

as a complex of rotating and oscillating movements that maintain themselves on their own power.

– Peter Sloterdijk, German philosopher

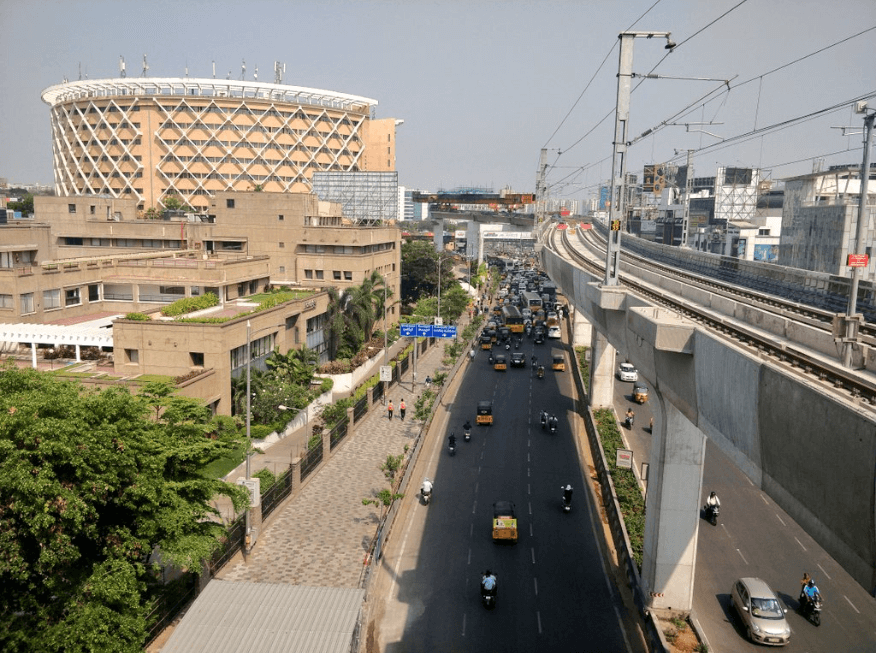

It is widely known that the city of Hyderabad was put on the pathway to globalisation in the 1990s under the leadership of Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu, who started a new course of high-technological market-led development. The state of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh (AP) was low on most indicators of development compared to the national average. Within a decade, it became an example of a state catapulting from agriculture to services ‘revolution’, which had largely failed to be a ‘force of growth and development’ in South Asia.

Very little is known about the role that the World Bank (WB) played by locking the state government into conditionalities of its pro-reform market-led development policies. This essay aims to foreground the state-level economic restructuring adopted in the mid-90s under the WB’s ‘Poverty Alleviation and Growth Program’. It sets the context to understand how the shift in economic policies ultimately changed the land planning and urban development by drawing parallels between the newly-proposed Bharat Future City and the three-decades old HITEC City.

Laboratory of anti-poverty programmes

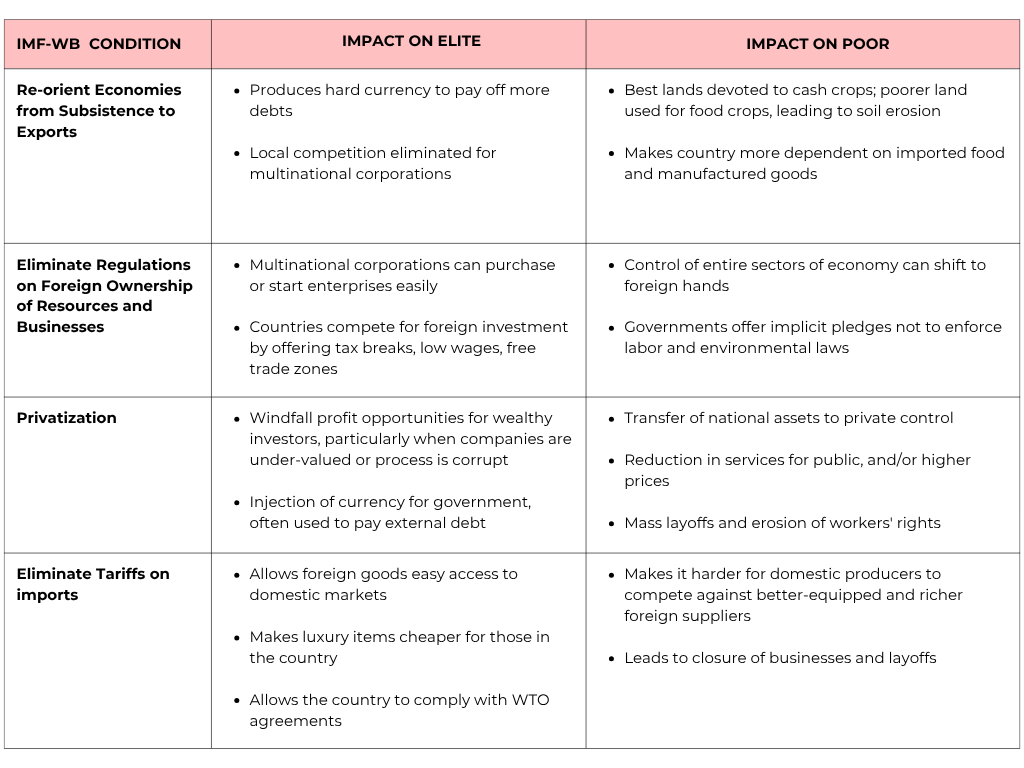

Following the ‘balance of payment’ crisis, the WB’s Structural Adjustment Programs – budgetary loans conditional upon the implementation of market-oriented reforms – led the process of economic liberalisation in India in 1991. In every country it operated, the WB prepared an aggregate long-term development strategy designing policies, programmes, and implementation. This was integrated into macro and sectoral issues with growth objectives and alleviation of poverty. While it ensured some level of modernisation and the creation of a ‘formal’ economy, it reoriented the challenge in policymaking of growth reducing poverty. In fact, the process of growth itself widened the existing inequality.

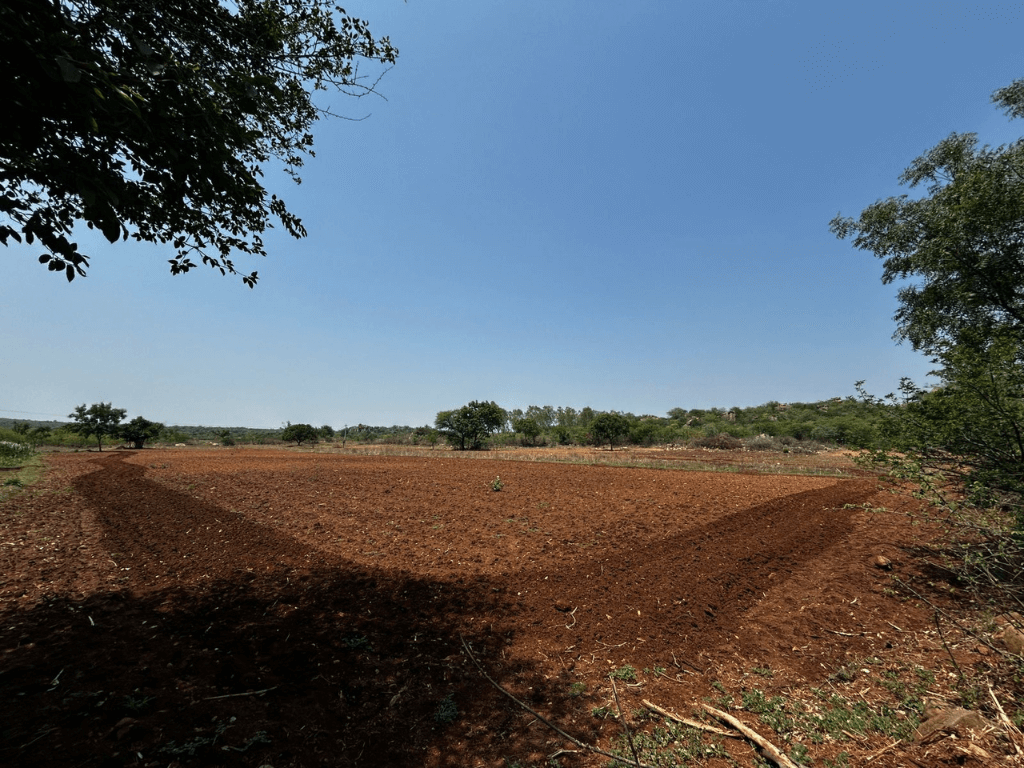

Photo: Ayesha Minhaz

India was the global laboratory for the WB’s anti-poverty programmes. Not satisfied by the speed of liberalistion at the national level, the WB used its resources and focus on the sub-national level. The erstwhile AP became the first state to overtly adopt and advocate India’s reform process and negotiate an independent loan from the WB. Thus, the WB came to play a critical role in formulating its developmental agenda and inducting its economy into the world market. The WB had a decadal history of programme-based loan disbursal in AP by funding seven of the 21 externally-aided projects by mid 1990s.

After a year-long consultative process of assessments with the state’s finance department, the WB concluded that the reduction of welfare programmes targeted at the poor and vulnerable groups through direct income transfers, provision of employment, subsidised food and housing was necessary to increase the development impact of its funding. A new poverty alleviation strategy meant market-oriented policies in sectors like health, education. The state government had to carry out macro-level and sectoral reforms to allow private investment in public sector industries and social sectors among other concessions.

The WB’s strategy involved three key components – privatisation of public sector industries (irrigation, power, energy, coal, agriculture), privatisation of physical infrastructure (ports, roads, airport), and privatisation of social infrastructure (health, education, child development etc.). It also emphasised the need of digitisation of land records for ease in land administration. The total cost of the reforms was estimated at Rs 3,300 crore. In June 1998, the WB entered into an agreement with the state sanctioning a six-year term loan of Rs. 2,200 crore towards implementation. The remaining had to be acquired by the state through counterpart funding (imports) but the state was already in debt of Rs 936 crore. The sub-national level lending was intended to provide a powerful ‘demonstration effect’ for the other states.

International developmental business

The idea of ‘leapfrogging’ from traditional agriculture to service industry had been CM Naidu’s dream. The ‘AP Vision 2020’ document was released on the Republic Day in 1999 aimed at poverty reduction, human development, and economic growth. It was loosely based on the analysis of the WB report that persistent neglect of infrastructure development was the reason for the lack of economic growth. The lack of investment was because public funds were used to combat existing inequality and gaps in policy for private participation in infrastructure development. Thus, economic growth, not welfare of the people, became the objective of the development rhetoric.

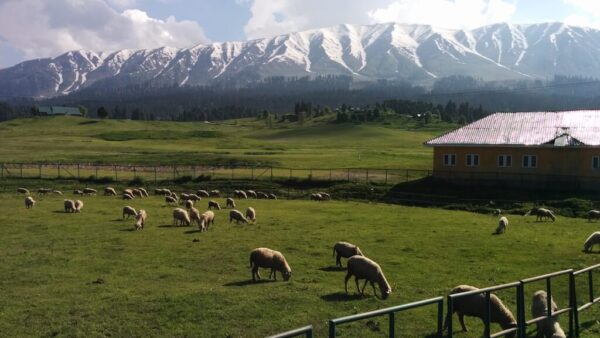

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A deeply entrenched relationship between economic development and reform process was established bolstering the loans as a necessity, and international best practices as the solutions without contextual diligence or local expertise involvement. Vision 2020 advocated not just for growth and development but also administrative reforms and governance. The creation of community-based organisations identified direct stakeholders for common resources such as land, water, forests who were made members of user communities but this diluted the control and role of public departments, allowing them to be privatised. A Centre for Good Governance was created to enable the transition within the state bureaucracy. It also acted as a think tank, a conduit to implement WB’s agenda.

Vision 2020 became a leitmotif of CM Naidu and the state became the WB’s first experiment in a sub-national policy-based lending programme. This helped Naidu cultivate his image, nationally and internationally, of a professional and practical administrator but it also allowed the WB to, while implementing its prescribed policy, take decisions on behalf of the government. And it led to the development of Hyderabad as the focus of the government resulting in neglect and distress in the rural areas. Several indicators on human development plummeted further. It changed the state’s policy process, formulating policies without debate or scrutiny, centralising powers to control decisions, and surrendering its own authority to external agencies. Not surprisingly, it also suppressed a careful analysis of the WB’s reforms and policies.

Land reforms for growth and poverty alleviation?

The success of liberalisation was, in part, in the focused effort at rebranding cities of the Global South as economic engines and directing loans for urban development. To keep up the momentum, reports were prepared on the global trends in urbanisation, growth projections of economic agglomerations, and the inevitability of service industry. The de-collectivisation of land was fundamental to this transition, therefore the need for individual forms of property ownership and digitisation of land records to bypass conflicts arising from unequal land ownerships.

The rhetoric of sustainable economic development also placed land policies at the centre of people’s well-being and good governance. It made a strong argument for the availability of economic opportunities for the poor folks through land reforms while masking how such interventions were aimed at enabling commodification and privatisation. Three tendencies in land reform policies followed—one was the tenure security under the guise of asset creation for the marginalised; second, the exchange and distribution of land to expedite access to ‘land poor’ producers; and third, the changing role of government in restructuring collective/public land.

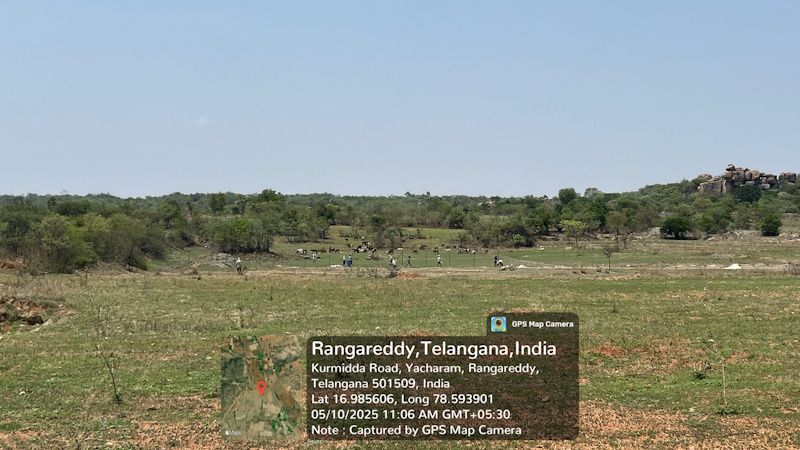

As a result, land was incentivised for development, enabling financial markets to use land as a collateral, finally impacting the government’s capacity to acquire and hold land for desired allocation and utilisation. Then, the competition to attract Foreign Direct Investment and export-centric industries led to large-scale acquisition of agricultural lands without consideration for food security, livelihoods dependent on them, and environmental concerns. The vigorous application of ‘public purposes’ clause of the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) Act led to one of the highest land acquisitions of about 2,00,000 acres for 109 approved SEZs. Land was readily and cheaply made available for contiguous industrial agglomerations with integrated townships, and to promoters, developers for indiscriminate speculation of real estate industry.

The potent combination of IT Policy of 1999 and the SEZ Act of 2005 led to the allocation of land to private companies for growth based on high-tech industries and services which has expanded in scope in Hyderabad and its peri-urban periphery. Despite the high socio-environmental cost of land alienation, disproportionate quantum of land acquisition, and allocation to profit-making private companies, this was termed as development. This leads to fundamental questions about who benefitted from land administration and reforms that were passionately implemented under poverty alleviation programmes, and who are the real beneficiaries of such developmental initiatives.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Vision 2047 versus Vision 2020

In June 2025, Telangana state, carved out of the erstwhile AP, prepared a ‘Vision 2047’ and entered a partnership with the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change for strategic advice, policy design, and global governance practices. This document is accompanied by a proposal of creating a net-zero greenfield smart city called Bharat Future City—a 30,000-acre flagship project of the current CM Revanth Reddy. A corresponding spatial planning of specialised zones will include AI City, Health City, Life Sciences Hub, EV and Energy Storage Systems all connected by new transport infrastructure developed along the proposed Regional Ring Road (RRR). It is buttressed by a slew of policies oriented towards industries and manufacturing with a range of incentives, benefits, waivers, and clearances, and administered through the ease of business indices, self-certification practices, and single window services.

This will be governed by structuring the state into three regions – core urban area of Hyderabad, a semi-urban region connecting district towns, and the rural region. While the proposal of Future City is new, its core area is a part of the Pharma City for which 14,000 acres were acquired by the previous government. A special development authority was constituted in March 2025 to cover 56 villages across 765.28 square kilometres, with a budget of Rs 17,677 crore allotted so far towards remaining land acquisition and planning. It marks a pivotal moment as it has become the modus operandi of the state government to launch projects and acquire land despite claiming to have the largest land bank in the country of 1,45,682.99 acres.

The planning of Future City closely resembles the planning of HITEC City and the Outer Ring Road. The iconic 10-storey ‘Cyber Towers’ built in public-private partnership is the first office building in HITEC City covering 52 square kilometres on the western periphery of Hyderabad and was the flagship project of then CM Naidu. The Master Plan for HITEC City evolved along an orthogonal grid with zones of residential and commercial interspersed by Cyber City, Knowledge City, Innovation City all connected by new road infrastructure and the Outer Ring Road. When the state’s first ICT Policy was released in 1999 to promote the IT and ITES-led growth, it included the repeal of Urban Land (Ceiling and Regulation) Act to allow industries to hold excess land for future transactions.

A Cyberabad Development Authority was constituted as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) which had legal and administrative power to acquire land, develop infrastructure, grant planning controls, zoning regulations, and so on. It triggered a trend of mega projects with similar IT Parks housing corporate offices, malls, residential complexes in gated communities, and premium educational institutions with state support in private development. Within a decade, the service exports increased by 45 times and the number of IT industries by 8 times, firmly establishing the ‘city’ as a centre of ‘service led economic growth’ and ‘poverty alleviation’.

Such projects increase the demand for scarce urban land leading to conversion of sub-urban agricultural lands into more ‘productive’ unmitigated operations of the land market. The rationale for land reforms to combine with the poverty reduction programme places the onus on the government owning large amounts of public land for housing schemes and other social infrastructure. However, once acquired, it creates conditions for market-led and policy distortions, commodifying land in the process.

The infamous Land Acquisition Act (LAA) is evoked to acquire land from communities to develop infrastructure, urban housing, speculative real estate, and SEZs. The declaration of intent to develop such a project not only increases land prices but also creates a phenomenal speculative demand for adjoining land, resulting in land notified and acquired even when the real land requirement is not substantial. Despite the availability of government land or identified ‘wastelands’ not suitable for cultivation in locations of proposed projects, it indulges in large-scale land alienation mostly from people belonging to poor and vulnerable communities.

The industrial policy of the state boasts, amongst other things, of sector specific ready-to-use land banks with the necessary infrastructure to save businesses ‘crucial time’. If the land is unsuitable, it includes the government’s willingness to acquire private land by applying the LAA and changing the land use for the benefit of the industry. Simultaneously, there is a provision to develop mini townships outside the industrial areas for residential purposes to be sold to private developers.

To bypass the complexity of consent and challenge of fair compensation, land pooling is adopted to expedite the process of urban development by aggregating land from individual owners, building physical infrastructure and redistributing it. This process is either done entirely by the corporation or in partnership with promoters by retaining 40 percent of the developable land to be auctioned in the open market at premium costs.

Photo: Catalytic Solutions, 2002

Conclusion

As of 2024, Telangana has a debt of Rs. 6,71,757 crore and its increase indicates dependence on external borrowings to cover expenses and developmental costs. A proposed solution is the fiscal reform to balance spending with revenue generation and reduce dependence on loans and aids towards long term economic stability. While service industries contribute a substantial 65.7 percent to the economic growth, the agriculture sector still remains a large employer. Land is critical here.

Although the state spends towards social infrastructure and welfare, its focus is entirely on the city, and within the city, on areas that can generate high growth. It warrants the question of the impact of second-generation reforms. The inherent flaws in the design and implementation of the Vision 2020 remain. By its own admission, the WB favours the economic interests of its multinational donors while the state debt continues to compound.

The pursuit of economic growth by setting up exogenous industries through foreign investment and real estate development is the ultimate objective of projects like HITEC City or Future City. The past three decades reveal the way in which external conditionalities of loans have driven state-led privatisation. Within the city, investments are focused on target areas in the periphery, deeply altering adjoining areas through speculative land acquisition and planning, amid promises of innovation and poverty alleviation. Given the opaque nature of these decisions, one can only imagine what future the third-generation reforms accompanied by an external corporate agency will beget.

References:

- Balagopal, K. (n.d.). Land Unrest in Andhra Pradesh.

- Department, P. (2024). Telangana Socio Economic Outlook. Hyderabad.

- Kennedy, L. (2007). Regional industrial policies driving peri-urban dynamics in Hyderabad, India. Cities, Elsevier.

- Minhaz, A. (2025). Retrieved from Frontline.

- Mohan, R. (2021). A Third-Generation Strategy for Accelerated Growth and Development in India. Centre for Social and Economic Progress.

- Rao, R. (n.d.). World Bank and Andhra Pradesh Economy.

- Reddy, N. (1999). Vision 2020: Myths and Realities. Hyderabad: Soundarya Vignan Kendram.

- US Network for Global Economic Justice. (2004). The IMF, The World Bank, and Structural Adjustment. The 50 Years Is Enough Network.

- V, H. (n.d.). Andhra Pradesh and the World Bank.

- World Bank . (2004). World Bank in India.

Arshiya Syed is the founder of an architecture and urban design firm Studio Maqam in Hyderabad, Deccan. She is a graduate from the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, and an Urban Fellow from the Indian Institute of Human Settlements in Bangalore. She was the recipient of QoC-CANSA Fellowship 2023 to report on climate change and cities.

Cover photo: Fertile agriculture land outside the Kurmidda village marked for acquisition. Credit: Ayesha Minhaz