A block on Hudson Street, New York, was renamed the Jane Jacobs Way in 2009, three years after the iconic and indomitable figure of urbanism passed away. The street in Greenwich Village, where Jacobs choreographed her most famous battles of urban renewal through the 1950-60s, may no longer host the “street ballet” that she famously described in her landmark book The Death and Life of Great American Cities given the gentrification it has seen, as have other parts of the city, but the ideas that Jane Jacobs advocated then have lost none of their relevance more than 60 years later.

In fact, as economies in cities around the world focus on the creation and concentration of wealth in a few hands while millions of residents in these cities – workers in these economies – struggle for basic amenities, the ideas that Jane Jacobs propagated back then invite us to revisit them. This doyenne of urban activism, with whom I had a personal connection too, is unlikely to fade from public memory given that her vision and ideas for cities still hold relevance – the sense of place, micro-level interactions, the street as a theatre of everyday ballet, the importance of neighbourhoods, the value of residents’ experiences in those neighbourhoods, and the resistance to top-down large city-building projects.

Above all, what Jacobs did through her lifetime beginning with her journalistic work in Architectural Forum was to remind us, over and over again, to view the city – any city – in deeper and more complex ways than what planners, policy makers and politicians do. She nudged us to not get drowned in the gleaming modern narratives of urban development which render several aspects of the city invisible. These, among the rich tapestry of her work, still resonate.

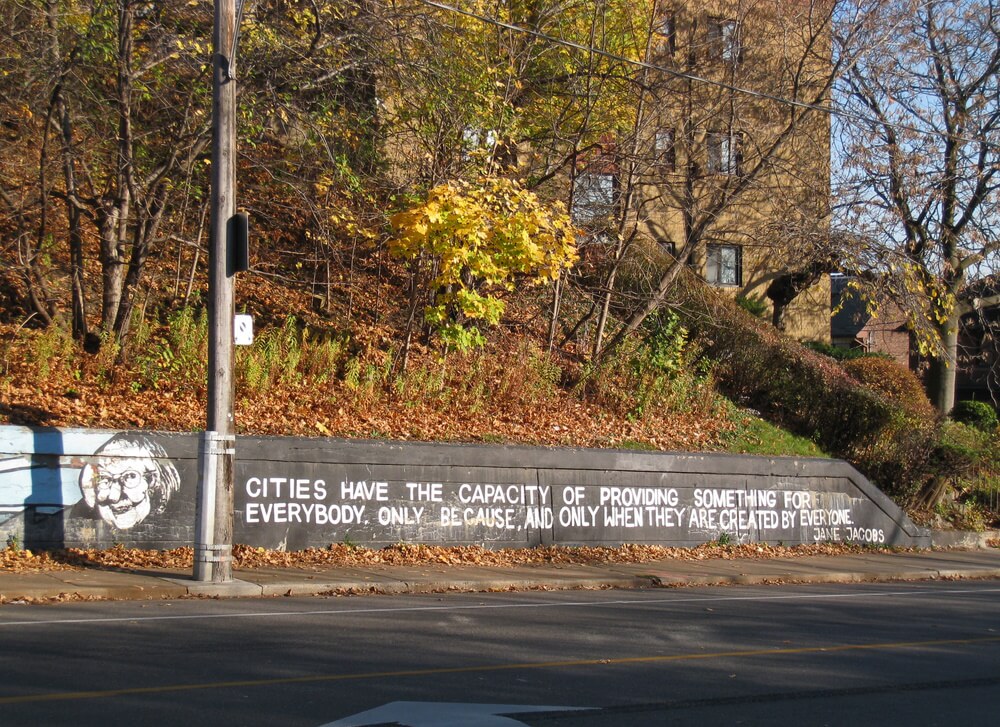

Jane Jacobs taught people to ‘see’ the city, to register and recognise the invisible. She reminded that while it may be de rigueur to discuss a city as an urban economy and its integration in the international economy as a global city, it has unmistakable sub-economies across its square kilometres where most of its residents belong, and city planning must account for them. As long as making this visible, bringing everyday people and places into urban development discussions, and foregrounding their concerns demand our attention today, Jacobs remains relevant despite critics who dismiss her ideas as utopian or romantic. When people in cities anywhere in the world fight to save their neighbourhoods, local economies, and green spaces, they knowingly or unknowingly invoke Jane Jacobs.

Jane made me think

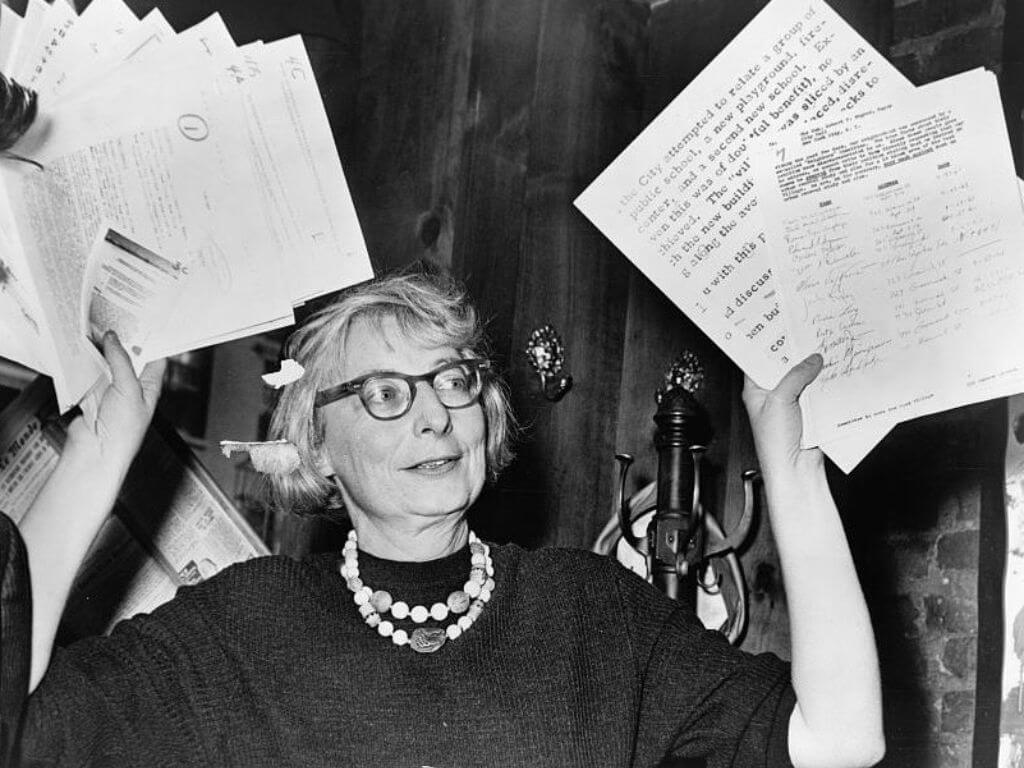

Years after she became a memory with her passing away in 2006, I still recall the large conference at which I spoke on urban economy with my usual gusto and confidence, perhaps a little too much confidence which came from being young and sure of my subject matter, as academics are wont to be. This little lady stood up, with her famous bob and glasses, and energetically asked me questions based on her experience on the ground. She made me think.

Jane Jacobs made me think deeply about urbanism, urban economy, people and place. I was young, new to New York, and keen on learning. She was formidable in her understanding of the city and realised that I took her work seriously. We hit it off well. I learned from her. She knew my work, had captured not only its good elements but also those which required more development. She always asked me good questions; she always asked questions to everyone. It was heavenly watching her – a short strong woman, holding her own in great meetings, debating with the big men. We cared about each other, I loved her.

In a huge city like New York, one cannot always be in the know of everything that is happening or read about it. We academics too may not be fully conversant with on-ground realities; we rarely know everything though we think we do. There are always stories that we overlook or never get to see and hear – unless we pay attention to what people like Jacobs bring to us. I valued her for that, deeply cherishing the relationship we developed.

Jacobs pursued a line of questioning quite different from mine. Even when we did not agree on everything, I saw that she always returned to the issue of “place” and its importance when evaluating the implementation of urban policies, she focused on the loss of neighbourhoods due to “development”, and she spoke of how people’s experiences were getting erased as the city developed. Thanks to her, my intellectual thought moved to embrace “micro” aspects in cities; I am still doing work on the need to re-localise national and city economies.

Jacobs had a formidable presence, both personally as well as on the issues she chose to pick her battles on, especially resisting the top-down plans, and has had a major influence around the world. I see now that some urbanists understood her battles and went with her but too many people did not put the effort needed to understand what her ideas were about. So, there has always been a mix of people who valued her contribution while a host of others – people and authorities – were unaware or simply indifferent to her. Now, there are people, later generations of immigrants – especially coming from Latin American countries with whom I work – who have not heard of her. I speak to them about her and her ideas, the ones relevant to their condition, but these are not always of interest to the immigrants.

The famous face-off, its impact

I tend to think that Jane Jacob’s famous battle with planner-administrator Robert Moses, the stuff of books and plays too, was a faceoff between two diametrically different approaches to the basic concept of the city. The battle and its outcomes have been well documented. Suffice it to say that the Jacobs-Moses faceoff, with all its drama and name-calling – he called her and fellow protesters opposing the highway through the Washington State Park as “nothing but a bunch of mothers” – stands at the beginning of a serious change in urbanism and city making.

Photo: Robert B. Moffatt/ Creative Commons

She showed that there was another way of building the city from what Moses had proposed and was presiding over in New York. We can all debate her, but what Jacobs left behind is the recognition of alternative ways of imagining our cities, alternatives to the capital-determined top-down plans. For this, we owe her gratitude. Both knew that it was war, that they were locked in a battle not merely of highways cutting across Greenwich Village and other neighbourhoods, but a battle of ‘seeing’ New York in certain ways and locating urban development in their visions – he top-down, bureaucratic and large-projects-based; she with the ground-up, people-centric, neighbourhood-based view.

Given Moses’ power then, her brilliant on-point analysis of what New York needed must have genuinely irritated him, to put it kindly. His hold over the city was “total” and he thought he was the master of the domain. Other architects and entities that depended on him would, so to speak, kneel in front of him. And then he was faced with this tiny but strong woman. He soon understood the power Jane Jacobs had among people and neighbourhoods. Moses succeeded in breaking quite a bit but in the long run, long after both the titans left us, it is Jacobs’ ideas of people’s needs which succeeded, in admittedly partial ways, in bringing positive elements into New York.

Jacobs’ New York today

Generically, I would argue that New York actually stands out as one of those cities that has had a long life and was once truly grand and famous, but is no longer quite what it used to be. The ironic twist is that the loss of its stature is at least partly due to the vast set of grand new buildings, and as anyone who grew up here or lived here long can say, New York was poor-ish though with its multiple histories, events, surprises and horrors.

The city, with its rhythms and spaces, made people like myself with modest incomes feel welcome. Despite its troubles and old infrastructure, it is still a destination for those who have never seen it. The old-ish city still has stunning architecture and inspirational energy. However, one outcome of development has been that lower and lower-middle income families, who used to live here and found it mostly a good place to be in, cannot afford to live a decent life today – everything is far too expensive.

As the city space has grown, mostly through spectacular housing and buildings, the modest classes have had to search for lower priced housing, often far from their jobs. This should make us think. Even the modest middle classes, let alone the growing number of poor households, are confronting a reality they had not quite expected in the city.

The Jacobs question

In many ways, Jane Jacobs lived and worked in a period which was both simpler than the one we live in and less dangerous than ours. The forces of globalisation and privatisation have led to certain impacts that were not present during the most active years of her life. However, knowing her the way I did, I think she would not have been happy to see the enormous growth of wealth and power in our cities which have left more and more people with modest incomes with fewer and fewer options.

We who care about cities should be alert to the growing distance that is taking place between the rich and the rest. Indeed, cities offer certain segments of the modest classes a great life, but too much is not going right for too many people. I find myself reflecting on what Jacobs might have thought about how our cities have changed, good and bad. The conditions that led her to fight have changed – big wealth has emerged as a major transformative factor, rendering the hard work of low-income workers invisible and the workers poorer.

But why should this be, she might have asked of those in charge of planning the city. Why should a city with enormous wealth so easily forget or not care about the growing burdens falling on the working classes which it depends on? This invisible injustice would have been unacceptable to her. Jacobs understood the risks and the enormous range of elements that are in play in building a city, and showed us a way to resist them through demonstrations, creative protests, interventions in public offices and so on.

We are, today, aware of the multiple ways in which a city is both a desirable condition and one that brings fear, pain, death. Reading Jane Jacobs in the present era means being aware of the need to be alert to all aspects of cities – continuously. It means recognising the vast differences which exist in large cities and also acknowledging the work of an enormous variety of often overlooked workers. And when faced with the challenges like she did, as informed activists in cities around the world do, it means to ask ourselves the question: What would Jane Jacobs have done in this situation?

Climate Change era

This means that we apply Jacobs’ benchmarks to present-day challenges such as Climate Change. She lived at a time when the Climate Change-induced challenges to life and work in our cities were not a particularly recognised aspect, Climate Change itself was not an issue. Jacobs’ battles then were with people in positions of power, who did not care about the city and what life it offered for the poor.

If she lived in our time, she would have engaged with the Climate Change issue. Jacobs would have had quite a sense about its global impact and how it affected people. Armed with knowledge and her battle-tested tactics of protests, she would have been working to alert us around the world to its hazards. Even now, in the United States, there are many who do not take this issue seriously. She would have contested this stupidity and fought it.

One of the aspects in play for her was her insistence – real insistence which could drive one crazy – that a city is more than its economy and its structures. She was convinced, and I respected it, that a city depends on the vastness of people and many conditions to make its urban fabric; she recognised and made us ‘see’ the different and small elements, rendered invisible by larger forces, that are needed in a city.

As in her time, now too on Climate Change, her presence and articulation would have been formidable. Jacobs’ approach was to contest the decisions and vision of powerful key actors in the city – some would have liked it, others not – but she would have done what she did best: persuade us to take the issue seriously, take our cities and their people seriously. Jacobs’ vision and agenda for the city serves us well even today.

Saskia Sassen, internationally-renowned urban sociologist, is presently Robert S. Lynd Professor of Sociology and Co-Chairs the Committee on Global Thought in Columbia University. Sasken is also the author of the landmark title The Global City among other books. Her research and writing focuses on globalisation, immigration, cities and terrorism, new technologies, changes that result from current transnational conditions, sociology of transnational processes and globalisation, and the dynamics of powerlessness in urban contexts and migration. Sasken shared a cherished relationship with Jane Jacobs.

Cover photo: Phil Stanziola/ Wikimedia Commons