The circle rates, or Ready Reckoner rates of land and property, in Gurugram were increased by 30 percent recently, making it the second increase in only seven months.[1] These decisions put apartments in the sought-after city, on the outskirts of India’s national capital New Delhi, out of affordable options for even well-placed people. Imagine the state of the marginalised who cannot even dream of basic housing in India’s cities.

Across India’s fast-expanding cities, land parcels on the edges have been agglomerated into urban areas ostensibly to create more land for more housing and amenities for people. The peripheral areas of Mumbai-Navi Mumbai are seeing this now, Bengaluru and Pune have expanded their boundaries, Hyderabad did it years ago to become the IT capital, and, of course, Gurugram stands testimony to how urban lands can be literally created. Logic would say that the increased supply of land, translating into more real estate and infrastructure in the cities, should make housing affordable and accessible to the large majority.

Yet, few can afford to buy or rent homes in these cities or access any of the amenities or spaces built. Houses, amenities, infrastructure all become out of reach for millions because land prices constitute nearly half of the cost of these constructions – and land prices remain high. Classical economics says that increased supply should have brought down land prices but this does not happen. Why land, as a commodity, does not follow the supply-demand equation, is a question worth probing.

This is because land prices determine so much in our cities – from who can afford what, who lives where, who gets to live in cramped inhospitable slums or in well-laid out apartments, who travels what distances and by what modes of transport, who has access to recreation spaces and open areas, how many green spaces abound or not, so on. It follows then that land prices cannot be left solely to the mechanism of the free market or cartelised so-called free market that has largely seen increases in the past few decades.

Land and real estate values may have stagnated, say during Covid-19 pandemic, but they have never declined or been corrected to reflect the needs of the largest number of people in cities. High land prices, artificially maintained or controlled by cartels of real estate moguls, have skewed the property market putting all categories of housing out of the hands of people, except the very wealthy. At a fundamental level, the high land prices have determined people’s affordability of homes, influenced their quality of life, and the very character of cities.

Can this be justified? Should this continue? The simple answer to both questions: No.

Land prices affect real estate

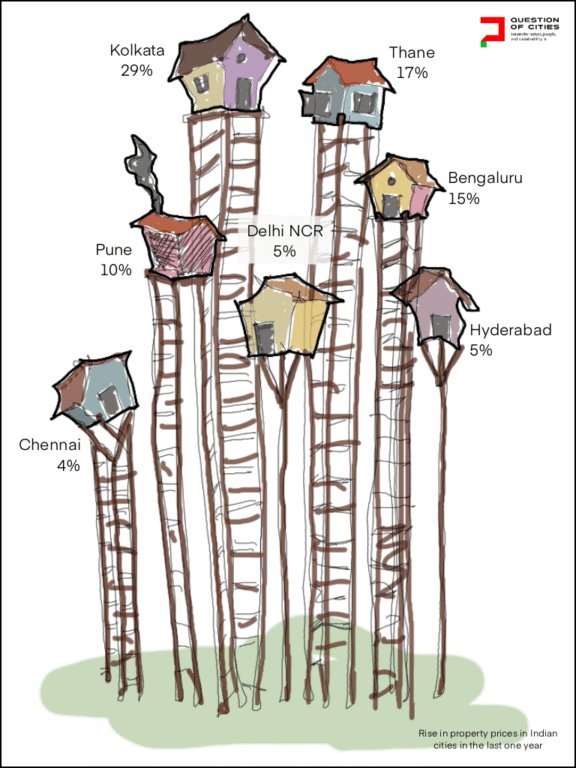

Primarily, rising land prices have meant higher costs of housing in every city. In the last one year, Kolkata recorded the highest housing price increase of 29 percent, followed by Thane by 17 percent, Bengaluru by 15 percent, Pune by 10 percent, Delhi-NCR and Hyderabad by 5 percent each, and Chennai by 4 percent.[2] Data analysed by Liases Foras, independent real estate research firm, showed that Mumbai’s average price for an apartment ranged from Rs 19,700 per square foot in Trombay and Govandi to Rs 1,05,993 in Pali Hill and Rs 1,20,000 per square foot in Cumballa Hill.

Based on data from the National Housing Bank (NHB), a publication surmised this June that, even a family with an annual household income of Rs 10.7 lakh would need to save for a staggering 109 years to afford a house of nearly 1,184 square feet in Mumbai while this would be 64 years of savings for a similar-sized house in Gurugram, 36 years in Bengaluru, 35 years in Delhi and 15 years in Pune.[3] The impact has been on sales. Housing sales in the first quarter of 2025 in India’s top seven Indian cities fell by 28 percent from the year before, a report for real estate consultancy Anarock stated in May.

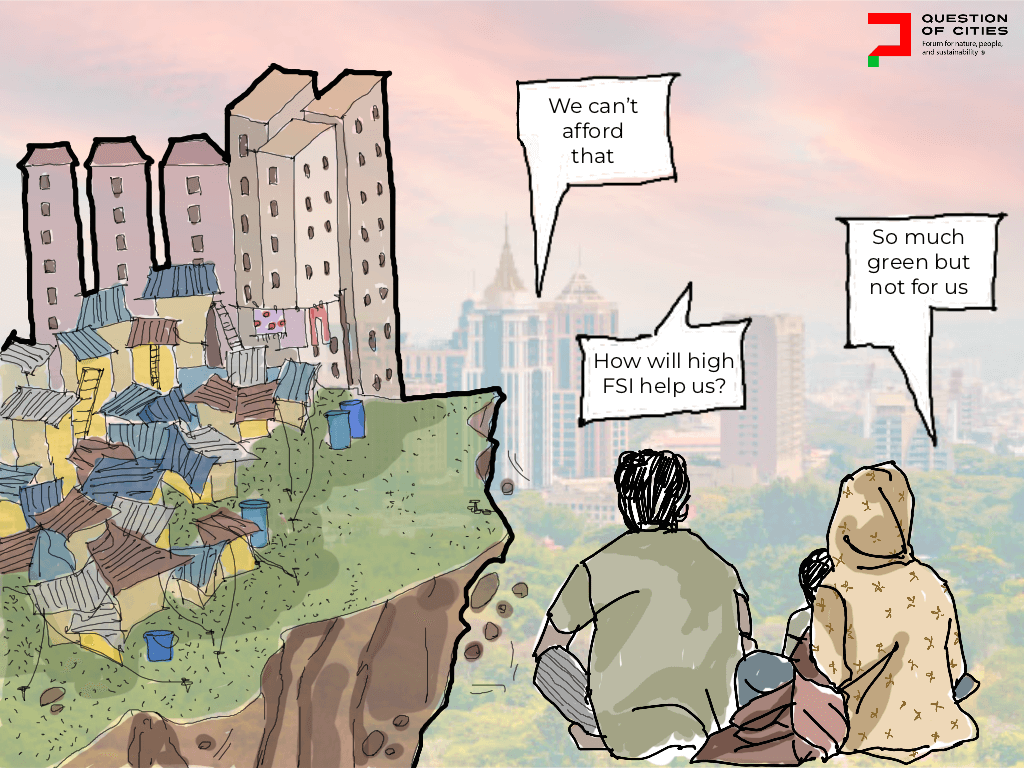

The affordability gap was striking but for the urban poor, this is stupendous. ‘Housing vulnerability’ which translates into lack of secure tenure, unaffordable shelter, poor quality housing, and inadequate access to basic services like water and sanitation is a part of their overall vulnerability. A proper home with basic amenities seems a dream, out of their reach. Slums become the only affordable option. And in slums, the quality of life suffers.

A study by Open City,[4] using GIS mapping and buffer zones around slum settlements in comparison to demarcated residential zones in Delhi, found that 373 out of 604 residential areas did not have a single government hospital in their area whereas 440 out of 685 slums lack access within one kilometre; approximately 90 percent of slums lack access to an Anganwadi within 250 metres. Going to schools far away meant money for daily travel; the compromise is to send children to local schools that are a picture of government apathy and neglect. There are no play spaces.

Land prices and equity

Besides location and infrastructure, the factor most affecting land prices is the Floor Space Index (FSI) or Floor Area Ratio (FAR) which is entirely a function of policies determined by governments. Increasing FSI/FAR and granting the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) in an area in return for a premium are instruments by which governments influence land prices. While the “proximity to major highways, disaster history, concentration of commercial establishments” affect land values, seen in a Thiruvananthapuram study, permissible FSI/FAR is a major factor too.[5]

The Maharashtra government recently announced an average increase of 3.89 percent in the Ready Reckoner rates for 2025-26. Accordingly, Thane will see an increase of 7.72 percent in real estate rates and Mumbai a 3.4 percent increase.[6] The real estate boom in Thane, according to this report, over the past three years, has meant a staggering 46 percent surge in average prices for middle- to upper-class residences. Where should the poor go?

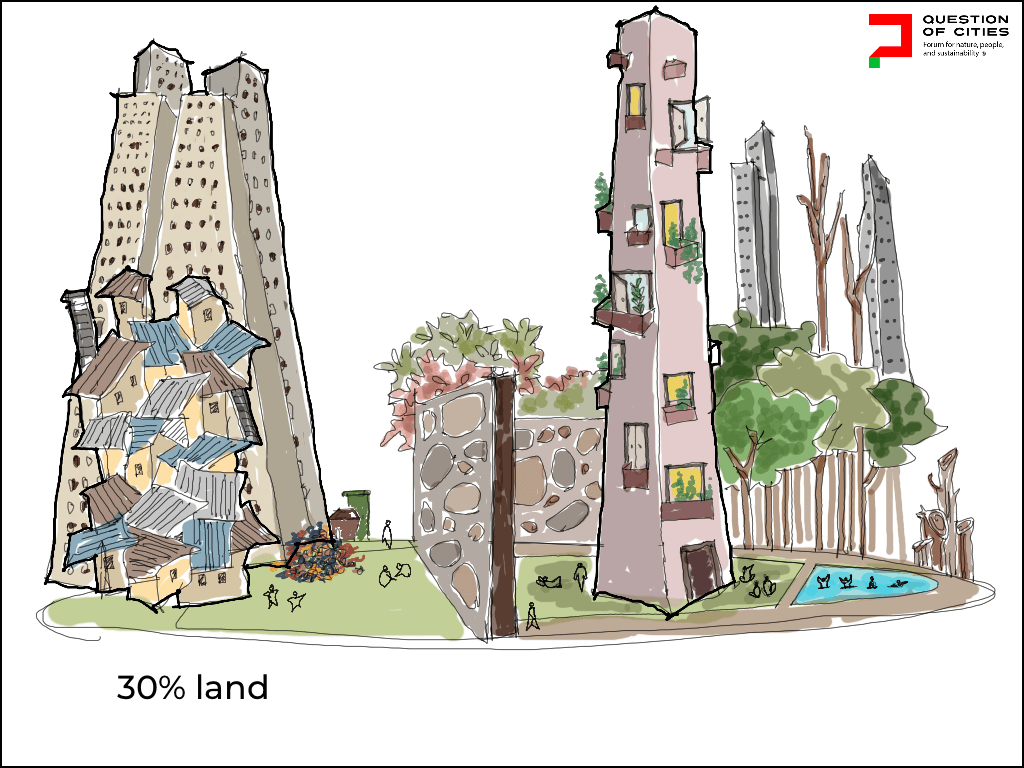

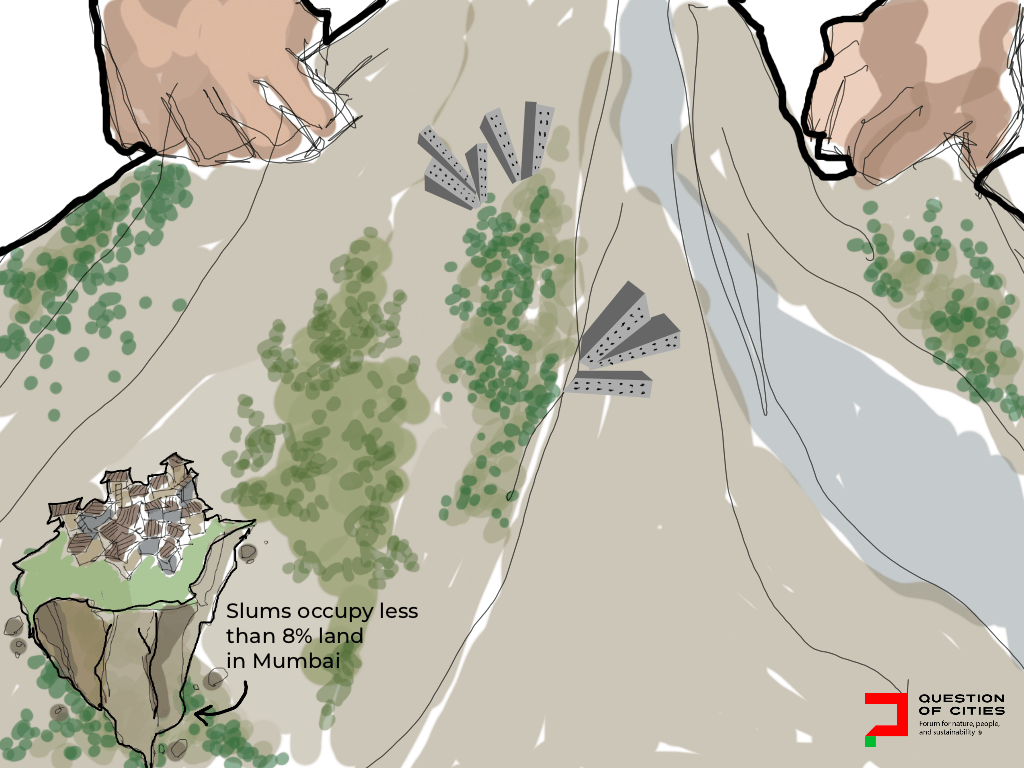

Land prices also impact people’s quality of life. In Mumbai’s slum redevelopment, high land prices have meant two starkly different typologies of housing on a plot and a skewed land apportionment. The rehabilitated buildings are squeezed into less than 30 percent of the land which means slum dwellers are forced to live in rudimentary and sub-par quality tiny houses with dark and dingy spaces, without light and ventilation. The major portion of the land is used for luxury high-rises with excellent quality construction, extravagant fittings, play spaces and vista views which are sold in the open market.

Different classes of people reside on the same plot but residents share neither the quality of housing nor access to the amenities. The cramped nature of the first and the spaciousness of the second has everything to do with how land is apportioned between the two types of buildings. Why don’t the slumdwellers get a larger portion of the land for roomier houses? High land prices, when capitalised in the free sale market, fetch enormous profits for real estate developers. They would naturally want to squeeze the poor into the smallest piece of the plot.

There’s nothing that stops them in this profit-driven enterprise -– except government stipulations, if enforced. If elected governments reflected people’s agenda, they would enact and implement land use policies that put quality housing within the reach of the middle and working classes. Call it socialisation of the land market or by any other name, but there is a role for governments to perform if the largest number of people in cities must have a decent quality of life and spatial justice. This is the beginning of the conversation about land or spatial equity in cities.

Government cannot escape its role

Ironically, this model exists, or existed. Government agencies or autonomous institutions were mandated precisely to make land available at low cost or no cost for housing and amenities for the public. The Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) in Mumbai and Maharashtra, and Delhi Development Authority (DDA), to name two statutory agencies, were set up to provide affordable housing to the lower segments of the population in the two expensive cities. Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) can be added to the list too.

These agencies made properties available at lower than the prevailing market rates in different areas mainly because they kept land prices low; they owned the land or marshaled it as a public resource for public good. Houses thus become affordable and accessible to many. But the number they put up for sale, inviting applications and selecting by lotteries, has been a fraction of the demand for such housing.

The land they own or manage is essentially public land. The rupture has been in the past few years as these statutory agencies devolved their remit to private players and reduced themselves to being project approval authorities even as the housing market succumbed to market forces and profit motives. Even if they partner private players, it is largely in name as a minority partner in a Special Purpose Vehicle.

The SRA has rehabilitated less than 10 percent of Mumbai’s slumdwellers while, since 1999, MHADA had managed to re-house tenants living in just 8 per cent of the total 16,000-odd pre-1969 cessed buildings. The DDA appears to have acquitted itself better both as a provider of houses and regulator of prices. The problem has been that the agencies are unwilling to pull their weight on land prices but have transferred their responsibility to private players. The private sector, of course, does not make housing affordable.

If housing in large cities should be affordable and accessible to many, then the way is to reimagine or reassert that land is a public good – from its allocation and ownership to how it is auctioned and to whom, what kind of housing and infrastructure should come up on it, and so on. The value of land is not merely its price but a lot more; it has social and cultural value.

The purely profit-oriented, not people-oriented, approach has meant that private players built houses that are lying vacant in lakhs even as affordable housing or public housing falls short. The supply of affordable homes in some of India’s cities dropped from around 3.1 lakh units in 2022 to under 2 lakh last year – a 36 percent drop in just two years.[7] The lack of attention to public housing has meant that even under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Urban (PMAY-U) itself, nearly 46 percent of the 9.69 lakh houses constructed for the urban poor[8], remain unoccupied due to incomplete infrastructure and delays in allotment, according to the Union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA).[9]

In this conundrum between the state agencies and private players, the public has the worst deal, especially those at the bottom of the economic pyramid. Can more people have basic quality housing and amenities? Indeed, yes, if land prices can be regulated and the state agencies discharge their responsibilities. This can happen only if the government of the day has the political intent to do so.

All illustrations by Nikeita Saraf