Since liberalising its economy in 1991, India has aligned with the neoliberal turn that has globally dominated public policy in recent decades. This philosophy believes private enterprise is inherently efficient, government inherently inefficient, and development should consequently privilege free markets, deregulation, globalisation, and maximisation of a retreat of government from public life.

This ideology has impacted the Indian city, opening space for private entities to enter domains earlier reserved for government, provoking an increase in privatisation of urban space that is not counterbalanced by any guiding vision of the Indian city as a public realm. A grassroots democracy of local urban governance is yet to take root. Modernisation has been predicated on a technocratic vision of governance that sees the city as a technical, rather than political or cultural, entity in which the horizons of urban planning tend to limit themselves to the logistical dimensions of zoning controls and movement.

The privatisation of Indian urbanisation takes many forms – a radical increase in gated enclaves; responsibility for social housing passed to private real estate through development incentives; major infrastructure projects executed by private-public partnerships whose financial models factor for private profit; shifting governance of public projects and precincts into ‘special-purpose-vehicles’ with substantive private funding; commercialisation of public parks and lakes through corporate sponsorship and control; a privately owned gig economy increasing share in urban mobility and services; financialisation of urban land to benefit private capital; and more. These modes of privatisation are not analysed here – there is adequate literature elsewhere on them – for focus is on an overarching question. Does democratic urban governance meant to serve public interest get compromised by increasing privatisation?

Imagining a city

To raise the question of urban public interest is to claim there is a shareable interest, which is to implicitly posit the city as a public community. Wikipedia defines community as a “social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place, a set of norms, culture, religion, values, customs, or identity.” It is easy to map this definition onto scales of community such as family or ethnicity, where origins by birth or social tradition play a defining role in the formation of community. A city, however, confronts every one of its dwellers with a self-evident scale and diversity that convincingly determines: (a) most urban dwellers are hidden behind a mask of anonymity; and (b) even if this mask could be lifted, shared histories, norms, values, ethnicity, class, or customs could be found only in a minority of the population.

James Donald, in his essay Metropolis: The City as Text, suggests that the word ‘city’ is a fiction for it “designates the space produced by the interaction of historically and geographically specific institutions, social relations of production and reproduction, practices of government, forms and media of communication, and so forth.” Lumping all this complexity and diversity under a single word ascribes a coherence that does not exist. Drawing from Benedict Anderson’s now familiar notion that the nation is an imagined community in which the modes of imagining the community’s coherence – symbols, discourses, fantasies, metaphors – warrant attention, Donald suggests we learn to critically conceptualise the city this way.

Imagining a nation is very different from imagining a city. The nation unites around the symbols of a flag and anthem, a boundary held steadfast by unified defence, a citizenry held relatively stable by immigration protocols, and, in the case of post-colonial nations like India, a date of independence ascribing a coherence that masks the fractures of pre-colonial history. In a city, a flag or anthem are rarely potent symbols, boundaries are continuously evolving, the city thrives on migration and mobility, and celebration of a founding date is rare. If we must examine the modes of imagining that make a city, we must come to terms with urbanism as a way of life; or as Jane Jacobs famously said in 1961, we must know “the kind of problem a city is.”

City as a conceptual model or living system

Urban planning as a discipline is largely captured by a dominant tradition that imagines the city as a conceptual model: a technical system deterministic enough to capture in a master plan that shapes the city’s inhabitation. This springs from the discipline’s history, emerging in the mid-19th century as an effort to deal with disease and dirt among over-crowded and poor urban populations produced by the Industrial Revolution. The first urban planning acts were sanitation acts, and this quest for technical purity rather than humanist foundations has shaped the discipline since.

However, there is another conceptualisation of the kind of problem the city is, one that sees the city as a living system in which people do not merely follow the dictates of a master plan, are creative in how they occupy the city, and the city as a dynamic, diverse, and ordered whole emerges from this creativity. A key thread that runs through adherents of this school is that they do not see the cosmopolitanism and anonymity of the modern city as obstacles to the formation of community. They are features rather than bugs, for they offer liberation compared to the constricting gaze of tradition in villages and small towns, freeing people from the pressures of conformance, allowing creative thought to flow into the new forms of innovation and association that a cosmopolitan modern economy needs.

Jeb Brugmann, in his 2009 book Welcome to the Urban Revolution: How Cities are Changing the World that includes field work in India, extends this line of thought. He identifies how urbanisation has always accompanied modernisation with cities producing a disproportionate share of GDP compared to their population, thus proving their inherent creativity. People can leverage several economies in the city: economies of scale (there are more people to connect with); economies of density (they are closer at hand, making connection easier); economies of association (scale and density catalyse new forms of association where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts); and economies of extension (scale, density, and association facilitate connection to economies beyond the city).

People leverage these economies in a multiplicity of ways, and Brugmann argues that rather than forcing everyone into the one-size-fits-all strategy of a master plan that specifies the city in detail, urban planning and management should empower these multiplicities and mediate clashes between them. A key case study Brugmann cites is Dharavi in Mumbai that, although labelled as a slum, contains several thriving enterprises including a few that have reached the level of sophistication to export goods to advanced economies in the West.

Land market, capsularization, fragmentation of space

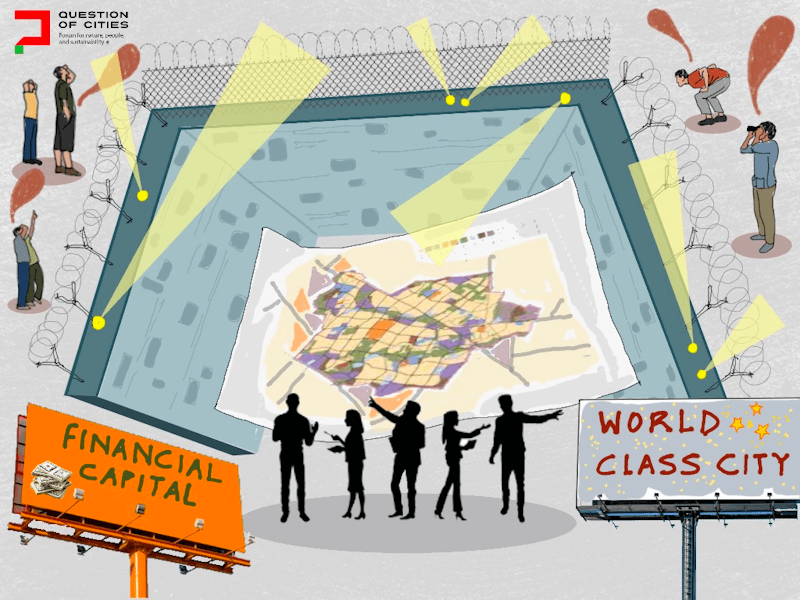

The city is fundamentally impacted by our choice of whether we imagine it as a conceptual model or a living system. The former firmly dominates planning and management in the Indian city. Planning is characterised as a technical project that operates behind a veil of professional and political expertise shielded from public view. The public realm is designed for the prosaic functions of networks of public utilities and access to functions of urban life.

Once a plan is in place, governance shifts to mere implementation without institutionalised checks assessing how effectively and inclusively the plan serves the population. This results in the Indian city exhibiting several fundamental fractures: Land markets rendered inefficient by opacity, corruption, and bureaucracy, exhibit high prices that bear no reasonable proportion to median incomes. Significant swatches of the urban population cannot afford to situate themselves in the city through means that correspond to the formally sanctioned master plan. They are forced into spaces outside planning – unregulated layouts, unsanctioned constructions, slums, building stock predating urban planning – with informal employment and under-employment dominating urban labour.

The urban poor and lower middle class survive because implementation of master planning is weak, granting them space for the informal systems of tenure that underpin their survival. While this grants them creative space to innovate on housing and entrepreneurship, it renders them vulnerable to dispossession, displacement, limited access to public services, a degraded quality of life, and poor upward mobility.

Images of development take precedence over systemic appraisals of development. Public discourse on urban development foreground mega-projects like flyovers, tunnels, or metro rail systems that lack last-mile connectivity, positioned largely to attract private capital that will sustain the visibility of other emblems of modernity such as office parks, apartment towers, and villas. Modernisation becomes an aesthetic project rather than one of ethical politics.

This aesthetic project foregrounds islands of excellence within an ocean of dysfunction. The elite sustain their way of life through what theorist Lieven De Cauter terms capsularization: navigation between these islands within the sealed and introverted capsules that are their private vehicles, thereby sustaining a comforting illusion of spatial continuity. This not only biases urban planning to privilege private transportation, but also pushes the ocean of dysfunction and its inhabitants into invisibility from the formal city.

Spatial discontinuities drive the real estate industry to market its projects as refuges from the city rather than networked with the urban condition, further exacerbating fragmentation of urban space. The increase in supply of public goods, such as healthcare and education, happens more in the private than public sector. This affects both affordability and quality.

The limited reach of master planning and governance allows informality to thrive at both ends of the spectrum, sheltering behind-the-scenes rent seeking action by the political and economic elite. As Ananya Roy notes in her paper Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities, “this idiom of urbanization makes possible new frontiers of development but also creates the territorial impossibility of governance, justice, and development.”

Does planning capture public interest or mask private claims?

An imagination of the city as a conceptual model translates the model into a master plan that rests on the claim that the plan will capture the public interest. We rarely realise that there is no such thing as an easily definable public interest; the reality tends to be a set of competing private claims to define public interest. This imagination of the city hides the processes by which the model is constructed behind a veil of expertise claimed by technical specialists and by bureaucrats and politicians who work full time in governance.

Dense technical description obfuscates whatever is revealed in the public realm, masking the visibility of private claims and empowering informality of the elite. Since a master plan is always a ‘work-in-progress’ to a functioning city, built symbols of the ‘proper’ model of urbanism it claims are posited as markers of movement toward the goal, and recognition of the extent of socio-economic exclusion produced by the model rarely enters the foreground of public attention.

The fractures produced by this imagination of the Indian city will be greatly exacerbated with an increasing privatisation of urban governance and space. Neoliberalism increases inequality, and we have seen a growing number of dollar billionaires in our cities whose financial success is often perceived as synonymous with broad expertise, granting them increasing influence in the corridors of power. Put this together with the fact that increasing privatisation breeds increasing opacity of the mask of expertise that power claims, and we have a trend that conflicts with the democratic ideal of power resting in the people as a whole. As Louis D. Brandeis, former justice of the US Supreme Court, said, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

A reimagination of the city as a living system will redefine ‘public interest’ as a process rather than a definable concept. This imagination would reject a corporate definition of efficiency, for living systems seek both resilience and efficiency, and this is possible only when they are inclusive, transparent, accountable, autonomous, and adaptive through a feedback loop that allows governance to act as a steward of the inherent creative energy of urban life.

Conceptualising a living system demands we recognise all life within it, and governance and planning would have to start with observing the patterns and potential of urban life, demanding an inclusive accounting for all dimensions of life in the city, both social and ecological. The myopic vision of the public realm limited to technicalities of movement and services must be broken to recognise a living and breathing civic realm, unleashing the full range of creativity with which the entire population is recognised and empowered to leverage the potential of the city.

This requires a radical decentralisation of governance and planning down to the neighbourhood scale, for it is only at that scale that inclusive recognition and local nuance can be recognised and accommodated. It calls for a shift to the ‘Principle of Subsidiarity’ that asks that the smallest scale be granted the greatest autonomy possible, and what cannot be done at that scale is delegated upward in the hierarchy – a far cry from the top-down model of control that currently prevails.

The fault lines in our imagination of the city are of particular concern at this moment in history, for we are in India’s urban century. For the first time in history, India’s urban population is expected to exceed the rural population by the middle of this century, and the future is tied to how we urbanise. We do not have a sustainable model of urbanisation, and the current trend toward privatisation will make the future even more perilous.

We must return to the stated, yet unachieved, objective of the 74th Amendment to the Constitution of India that sought to transform urban local bodies into “vibrant democratic units of self-government.” Imagining Indian cities as living systems demands that we simultaneously and continually confront two key intertwined questions: what kind of city we want and what kind of people we want to be.

Prem Chandavarkar is a well-known architect, academic, and writer based in Bengaluru. The managing partner of CnT Architects, an award-winning and widely published architectural practice, and an academic advisor and guest faculty at Indian and international colleges of architecture. He writes and lectures on architecture, urbanism, philosophy, politics, education, environment, art, and cultural studies.

Illustrations: Nikeita Saraf