Rapid and rampant development of cities has resulted in significant changes in land use, leaving very little space for the public and making land use highly inequitable. Mumbai’s Development Control Regulations (DCRs) say that 10 percent of land should be open to the public but even this is not followed in land use distribution across the city. In Mumbai, as in many other cities, the planning and regulation of land use comes with a premium which increases the cost of land, adversely affects its supply, and makes public projects including housing unviable in market economic terms.

Prof Aneerudha Paul, who was the Director of Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies (KRVIA), Mumbai, from 2004 to 2021, speaks to Question of Cities about the growing privatisation of land, how to make land available for the public, and how the community-based approach for redevelopment will help.

Land use determines everything in a city — how people live, if the city serves a large number of people, what the marginalised can claim. On what principles does land use rest?

I live on the periphery of Mumbai. There are land use plans that governments have prepared including the Development Plan but in reality, land use does not get realised the way it should be. While there are certain principles in planning for an ideal city, the reality is very different. There is a premium to planning and regulation that we see in our cities. Whenever we plan, immediately there comes the real estate interest which instantly increases the land price.

Many underprivileged people in our cities live outside regulation and planning, they live in places where land use has not shown them as people they are. This is how it plays out in reality. If the government wants that the principles of equitability, sustainability, and inclusiveness are followed, then it needs to be dynamic and understand how things are playing out on the ground, and change land use as needed. In Indian cities, land use planning puts a premium on land which then makes it unaffordable for people whose needs need to be addressed, for which the government then gives them subsidies. This is what we see in cities like Mumbai.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How do you see the growing privatisation of land, if not in ownership then certainly in use and governance?

This is worrying as there seems to be a growing privatisation of land, especially given today’s context where governments are no longer taking the onus of planning new cities. When governments do not plan properly, they leave the process of land acquisition and land amalgamation to private interests without clear regulations and laws.

In cities like Navi Mumbai which were built in the 1960s, the government played a large role in acquiring land. But, in the peripheries, governments don’t play this role anymore. It’s the private interest that accumulates land through force or power. This is a big problem. Some places like Gujarat are trying to address this by having stakeholders get a fair share. But this is not happening everywhere. Private interests amalgamating and acquiring land in our cities is very worrying because not all stakeholders get a fair deal.

How should public interest feature in land use policies in cities like Mumbai?

Public interest should feature at all levels of land use policies, especially in Mumbai, which is driven by strong private and real estate interests. The question is how do you bring back land for public interest in these conditions. It is not an easy question to answer but we have to make everybody responsible. We have to make a real estate developer answerable for how to make land available to the public. It cannot be that they accumulate all the land and use it. Cities like New York and Tokyo[1][2] have tried some experiments. I don’t know how successful it will be in a city like Mumbai.

We can hope that governments want inclusive and equitable cities where even private developers play a role. Though they develop their own parcels of land, some of it should be public. Manhattan, New York, has tried something called the private open public spaces (POPS) and generated a public realm.[3] I know many people are critical of it because the private still controls it but it is open to public, there are regulations stating how it should be open, and cannot be cordoned off.

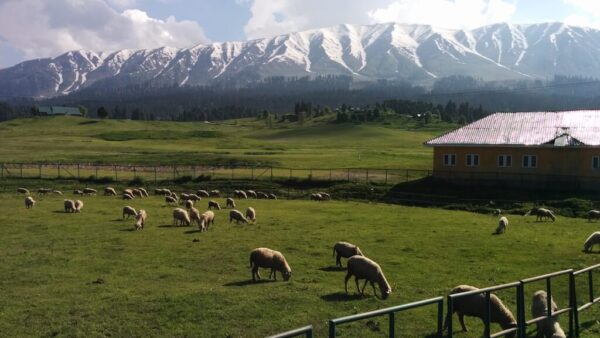

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

I think cities like Mumbai can attempt this if governments have a good heart. One of the Mumbai DCRs says 10 percent of land should be open to the public but it’s not followed. With the DCR, we need local area plans too which lay down where the 10 percent should be, it shouldn’t be in a godforsaken rear of a plot that nobody can access. You require sophisticated mechanisms of land use and development control regulations to generate this where private developers have to leave 10 percent land in parcels. I am talking all this but, in reality, we don’t know if it can function because there is surveillance of different kinds – compound walls, guard posts, bollard posts – which come in the way of making land public or open for everybody. So, it’s layered. The DCR and governance together make land available for people.

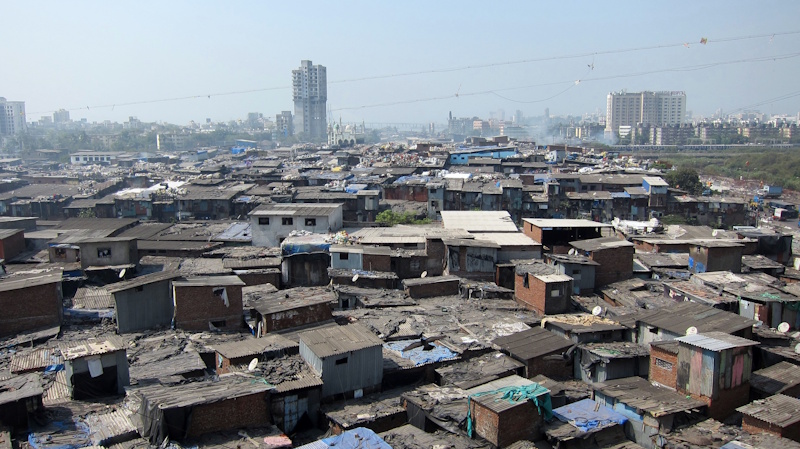

Isn’t a scheme like the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), in which slum dwellers are squeezed into barely 25 percent of the land while the rest is commercially exploited, a failure of just and equitable land use?

I agree. I don’t know the percentage but I am looking at it from the living environment created due to this land distribution. The living environment in these buildings is far from good – light and ventilation does not even reach them which creates conditions that lead to disease. The purpose of planning was to avoid environments which create squalor and disease, but we now have the same problems and serious health concerns. Whether it is a mere 25 percent or not, unless it’s addressed, we are not building a good city.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How can this be remedied and by which agency?

It’s not like there are no remedies. It’s a question of what the government is interested in. In most cities, governments seem to valorise the idea of private interest because that gives them taxes; it’s a revenue earner. Then, nothing can be done. To remedy, they have to start with the question of how to provide housing to the vulnerable people or what can be done when the vulnerable have self-organised settlement at a lot of places. Rehabilitation must address their interest. The Dharavi redevelopment must be driven by the idea that the community must be rehabilitated first. Can this be made viable by taking up a model with the sale component? Maybe yes.

The remedy could probably come from within the present models. If it’s a community-centric approach, the problem can be addressed. If the community wants to go for incremental development in the peripheries of a city, let that be. Let them choose the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana or other schemes to access money to build their houses. If the community wants redevelopment, let them choose an approach and sell land for the project. This is where the question of power comes in – who the powerful stakeholders are and whether they will allow this.

Housing is an outcome of land policies and the shortage of housing is linked to so-called unavailability of land. How do you view this?

The shortage of housing is linked to policies that led to a lot of premium housing being built and these houses lie vacant. There is a viewpoint that says that the market will correct itself and the land prices or house prices can come down. But is it really affordable for the urban poor or the vulnerable? I have never seen it happen. Whatever the market proponents say, it doesn’t happen even in the peripheries of the city.

I live in Vasai-Virar (about 60 kilometres from Churchgate in south Mumbai) which is considered affordable but many still can’t afford it. So, what do people do? They settle in land parcels such as the green zone and make slums. These lands are not supposed to be urbanised. In many cities, Pune and Pimpri-Chinchwad, the Maharashtra government has regularised informal settlements. Planning comes later, if at all. It’s the same story with the urban villages of Delhi where 40 percent of the people live but which are outside of planning. So, planning is a response to what has happened. And, therefore, attempts to generate land for people – the poor and migrants – through planning have failed. Ultimately, it’s a question of who controls the planning discourse.

How can housing be made more available and accessible in Mumbai? What should be changed about land use policies?

I can’t give you easy answers about how housing can be made more available but I hope that the processes are open for public scrutiny and people play an important role in articulating the need for housing. I won’t use the word ‘affordable’ because it should be priced much lower. Only then can we address housing needs of the people who are important to our cities, who serve our cities, such as construction workers, transport workers and domestic help. Cities are extremely hypocritical in not providing them housing.

It’s not a problem of policymaking or not having instruments. It’s a question of changing the planning discourse to make it more inclusive – for which governments and all stakeholders have to agree. They have to understand that infrastructure like housing needs to be built for people who serve cities. If this happens, then we may see inclusionary housing and more community-driven approaches to redevelopment.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

How can congested cities ensure that open spaces are preserved? How can land use policies help this?

This can be done not just through land-use policies but also through governance. An example is the privately owned public spaces in Manhattan that I spoke about.

Whoever participates in our cities needs to play a role. At the heart of this idea are questions of what is open for the people and how can a robust and resilient public realm be created. It should be everybody’s concern, not just the government’s; private interests in our cities should be concerned that while they make profits, they contribute to the public realm too. This has happened historically. In Mumbai, philanthropists played an important role in providing housing and a robust public realm. If we can change today’s planning discourse, we can create a robust public realm.

How can public scrutiny of land use plans fortify land as a common property resource?

The pressure has to come from people. This is very important. Governments must also respect public opinion. I don’t believe that today we can plan a ‘Navi Mumbai’ the way it was done in the 1960s but we can correct our cities, correct the current paradigm of development, if people are allowed to participate in the planning process, and carry out corrective actions incrementally. This includes people who provide services in cities. The Right to the City is about them having the right too.

Cover photo: Sourav Das/Flickr