Forests are among the most biologically active terrestrial ecosystems, providing various ecological services and playing an important role in maintaining the ecological balance even in cities. In a congested metropolis like Mumbai with few green spaces, urban forests help maintain the micro-climate, enrich the groundwater table, and curb air pollution. Despite these valuable ecological services, deforestation has become very rampant on one pretext or another. It has become imperative and urgent to identify and protect the remaining forest areas across Mumbai.

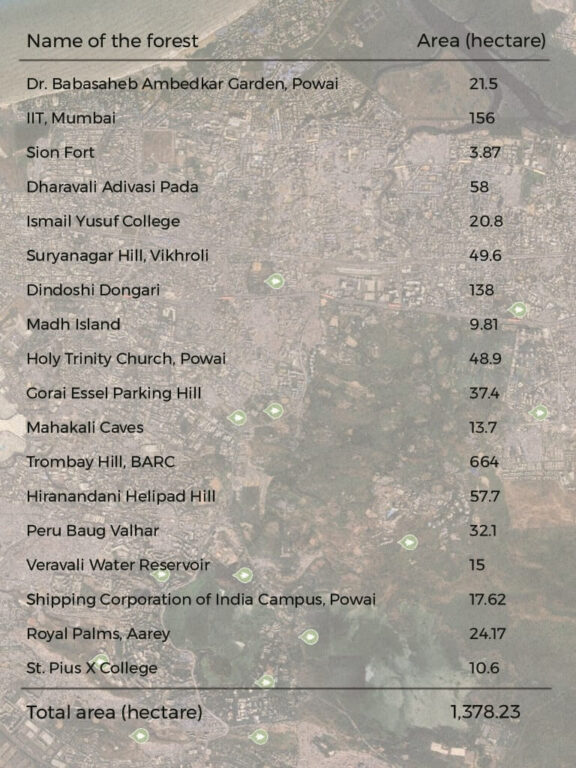

The Vanashakti team (see credits at the end) mapped the forests and floral diversity at 18 sites in Mumbai between June 2021 and October 2022. These are the unrecognised and missing forests in both the official records as well as in public imagination. These 18 locations, with total green cover spread over 1,378.23 hectares, are spread from Sion and Trombay to Powai and Goregaon covering old neighbourhoods and suburbs and accounted for a total of 13.78 square kilometres.

Of the 18 study locations, Trombay Hill at the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre has the highest, followed by IIT-Bombay and Dindoshi Dongri. While more mapping is needed, this exercise assumes significance because these urban forests are vulnerable to being damaged or destroyed for development. The city has to ensure that they are not treated as isolated disposable or construction spaces, but as valuable green spaces which complement our daily lives and well-being.

Across the 18 urban forests, our team found a floral diversity of 111 species belonging to 42 families. These encompassed five herbs, three climbers, 14 shrubs, grass, fern, and 87 angio-spermic trees. We adopted an area-centric endemic approach with a focus on exploratory research, and conducted a primary in-person observation of the ecology, biodiversity, and interactions. Additionally, the team did research to document the contextual and historical importance of these forests as well as the communities that depend on them and interact closely with them.

Photo: Vanashakti

Why forests are important

Since the emergence of life on earth, vegetation has been a crucial component of the ecosystem. Life, directly or indirectly, relies on vegetation. The extent of the land occupied by natural vegetation is referred to as forest cover. Forests are the abode of innumerable species of birds, animals, insects; they also function as the abode of many tribes, supporting, enriching several native practices and civilisations. They guarantee safe areas for floral and faunal species that are crucial to the stability of the ecosystem. Forested hills, with their variable altitude, allow a broader diversity of species exclusive to these areas.

Forest cover and trees help to control soil erosion, the deep penetration of roots creates a pathway for water and helps increase the water table, and the interlocking of soil by the extensive root systems works with soil microbes to enrich the soil quality. Their absence means a greater risk of flooding and landslides due to rainwater runoff, threatening the lives of those who inhabit hills as well as those in the lower regions.

People and corporates began exploiting forests for food, medicine from herbs, wood for building shelters and other purposes, seeing economic value in them. However, their ecological role far outweighs the economic aspect. In cities, this balance between ecology and the economic aspect of forested areas becomes even more urgent given the intense pressure on land and creation of land banks. Over the past few decades, Mumbai’s natural landscape has come under severe pressure. Housing needs and commercial exploitation seem to be nibbling away the green cover as the demand for resources (land) increases, in addition to the dumping and discharge of waste and wastewater. A classic case is of Metro 3 car shed located in the Aarey Forest which led to the demand for land[1] for a control centre, a commercial hub, a slum rehabilitation project, a regional transport testing centre.

Photo: Vanashakti

Trees have played an irreplaceable role in curbing atmospheric pollutants, sequestering carbon, and reducing greenhouse gases by acting as a medium for gaseous exchange. Providing oxygen also impacts the existing biodiversity, which is important for the normal functioning of maintaining the micro-climate and reducing the temperature. The decline in forest cover also impacts existing biodiversity, which is important for the normal functioning of the environment.

A study published in Springer’s Journal – Nature in July 2020[2] (Rahaman, S. et.al. 2021) found a 42.5 percent decline in Mumbai’s green space over 30 years.[3] Along with unsustainable development, Mumbai’s forests have also seen an increase in wildfires from 702 incidents in 2014 to 3,487 in 2017.

Despite the knowledge of Mumbai’s forest cover, little or no effort has been made to identify and protect it. The vulnerabilities and challenges presented by massive population growth, climate variability, and massive human-induced alterations of the terrestrial landscape (Alkama and Cescatti, 2016)[4]; Steffen et al., 2015b)[5] necessitate a much faster response to and resolution of this debate than has been possible. We are at a crossroads in time and history.

Photo: Shivani Dave

Accurate mapping

An accurate assessment of forests in Mumbai is essential to ensure that they are protected from further destruction. In an affidavit filed before the Bombay High Court, the Forest Survey of India submitted that “the forest cover of the Mumbai suburban district as per the latest forest cover assessment of Forest Survey of India, as published in the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2017, is 140 square kilometres (Moderately Dense Forest of 67 square kilometres and Open Forest of 73 square kilometres).”

Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park is spread across 102 square kilometres while the adjoining Aarey covers approximately 12.4 square kilometres which makes a total of 114.4 square kilometres. If the overall is 140 square kilometres, there exists a gap of approximately 25.6 square kilometres of forest cover. Therefore, Vanashakti initiated this study to locate and inventorise what is not reflected in the government records. We were able to map 13.78 square kilometres.

The purpose was to obtain preliminary estimates of the forest areas that had been overlooked or not formally surveyed. This study, we intended, would serve as a guide for a complete analysis later. Our focus was to (a) locate areas of Mumbai that can be quantified as forests and (b) compile a preliminary database of the flora found in these forests.

The selection of the study area was done through a geographic information system (GIS). Locations with an area of more than one hectare of green spaces on satellite images of Mumbai were identified and mapped. A review of the available literature on plant diversity in these areas was carried out. Then, our floristic research was carried out from June 2021 to October 2022. Field surveys were done to assess the plant diversity, during which a checklist and field notes were prepared. Specimens and photographs of unidentified plant species were collected for review.

Source: The Missing Forests of Mumbai

Some forests of Mumbai

1. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Garden – 26 hectares

Located near Powai Lake, this is also known as Powai Garden or Deer Park and is surrounded by a thick forest that spreads over 26 hectares. The green cover is about 21.5 hectares. This is the only park of its kind with the large Powai Lake adjacent to it. We encountered 43 species of plants and shrubs here.

2. IIT-Bombay – 156 hectares green cover

The internationally acclaimed Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) – Bombay is considered one of the green educational institutes in Mumbai. Its campus encircles the Powai Lake and a part of Vihar Lake, which are significant wetlands in Mumbai. The campus has an area of about 220 hectares, out of which 156 hectares is green cover. This is the most important area for sustaining biodiversity since it is connected to the Sanjay Gandhi National Park to its north. In 2008, the World Wildlife Fund carried out a biodiversity study here led by the noted ecologist Dr. Goldin Quadros which is testimony to its standing as a biodiversity hotspot – unique for a campus. The floral diversity here includes 50 species of plants, including Curcuma Aromatica, which is threatened as per the IUCN Red List category.

3. Suryanagar Hill, Vikhroli – 49.6 hectares

The Suryanagar Hill lies to the southeast of Powai Lake and Vikhroli, surrounds the hills in the east, Varsha Nagar in the southwest, and Godrej hill and colony in the south. This is a continuous range of the Sanjay Gandhi National Park hills and its forest cover is about 49.6 hectares. Suryanagar is identified as one of the unsafe areas as landslides during the monsoon are common. We found 36 species of plants but the forest is under severe threat due to encroachment and excavation.

4. Dindoshi Dongri – 138 hectares

Dindoshi Dongri Hill, located in the suburb of Malad east, is spread over 138 hectares. It is close to the Tulsi Lake and adjacent to the heritage site of Kanheri Caves. It is surrounded by a thick forest rich in floral diversity. This hill has various indigenous community settlements, such as Barik Pairi, Bhatukli Pada, Pimpri Pada, and Appa Pada, but the area is a habitat for leopards and spotted deer too. We found 40 species of plants, including Strobilanthes Callosa, which blooms once in seven years and is listed as threatened by the IUCN Red List. Two of the hills show rampant and steady deforestation. Water courses, especially of Oshiwara/Walbut River, are being altered and blocked by a landowner inside a heavily fenced boundary.

5. Holy Trinity Church, Powai – 48.9 hectares

The Holy Trinity Church, or the Most Holy Trinity Church, is a Roman Catholic 15th century church in Powai whose current structure has been rebuilt. The forested area of the church is around 48.9 hectares. However, the forests are undocumented and encroached by slums. They are also used for defecation and goat-grazing due to the lack of protective measures. We found 42 different species of plants. This forest needs urgent protection.

6. Gorai Essel Parking Hill – 37.4 hectares

Also known as Gorai Dongar Pada, it covers an area of 37.4 hectares. Geographically, it is located to the south of Uttan village in the northern tip of Mumbai where the ecologically significant mangroves are found. However, this forest has faced threats of destruction and encroachment since the establishment of the EsselWorld amusement park in 1989. The parking area on the foothills of Gorai Hill may be encroached in the near future; urgent steps are required to protect this area. A total of 48 plant species were recorded here.

7. Trombay Hill, BARC – 664 hectares

Trombay is one of the seven islands that make up the old city of Mumbai, and possesses a great history of the Portuguese and British era. For decades, the island has served as home to Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC). Trombay hill is spread across 664 hectares with a dense green cover. A detailed account of the flora could not be studied because it is under the control of BARC which, as a high-security area, prohibits entry for citizens. However, previous research suggested 32 species of plants, including Strobilanthes Callosa, which blooms once every seven years and is listed as threatened by the IUCN.

8. Hiranandani Helipad Hill – 57.7 hectares

Of the range of geographical features in Mumbai, this hill range in the northeastern-north stretch stands out. Commonly known as the Ghatkopar Hill, now referred to as Hiranandani Helipad Hill after the real estate company, it lies to the south of Powai Lake and extends from Ghatkopar to Asalpha Village. Even after the northern area of the hill was flattened in the 1980s by the real estate developer for an upmarket township of residential and commercial complexes, the green cover here spreads over 57.7 hectares. We found 38 species of plants. The hill was a reminder of the forest that once was before the concrete jungle replaced it.

Photo: Siddhesh Pisal

The other 10 forests include Sion Fort (3.87 hectares), Dharavali Adivasi Pada (58 hectares), Ismail Yusuf College (20.8 hectares), Madh Island (9.81 hectares), Mahakali Caves (13.7 hectares), Peru Baug Valhar (32.1 hectares), Veravali Water Reservoir (15 hectares), Shipping Corporation of India campus (17.62 hectares), Royal Palms Aarey (24.17 hectares), and St Pius College (10.6 hectares).

These are the last standing forests, the natural shields, of Mumbai which keep the city livable but they are scattered and lie neglected, abandoned, unrecognised, uncared for and unappreciated. A hundred saplings cannot replace the ecological services that a full-grown tree provides. Yet, the coastal forests are home to garbage landfills, roadside trees have died or are skeletal structures thanks to the mindless chopping of branches, which coupled with concretisation has resulted in steady depletion of shade and habitat for biodiversity.

If Mumbai has to be livable and support biodiversity, it is imperative that these forests are protected from felling. The Mumbai Climate Action Plan, a much- publicised document, does not even reflect the need to notify and protect these vital forests to help fight climate change. Experience shows that such forests are systematically bulldozed simply because they are “not notified” just as the Aarey forest was. It is the duty of the state to identify and protect forests using all available means. The inter-generational ecological equity cannot be diminished or destroyed.

We appeal to all the governmental bodies to protect and conserve these and other unrecognised and unidentified forests of Mumbai.

This report, led by Stalin D, was authored by Chris Varghese, Chitra Mhaske, Pawan Patil, Vicky Patil with field investigations conducted by Aslam Saiyad, Kaustubh Bhagat, Pawan Patil and Vicky Patil

Cover illustration: Shivani Dave