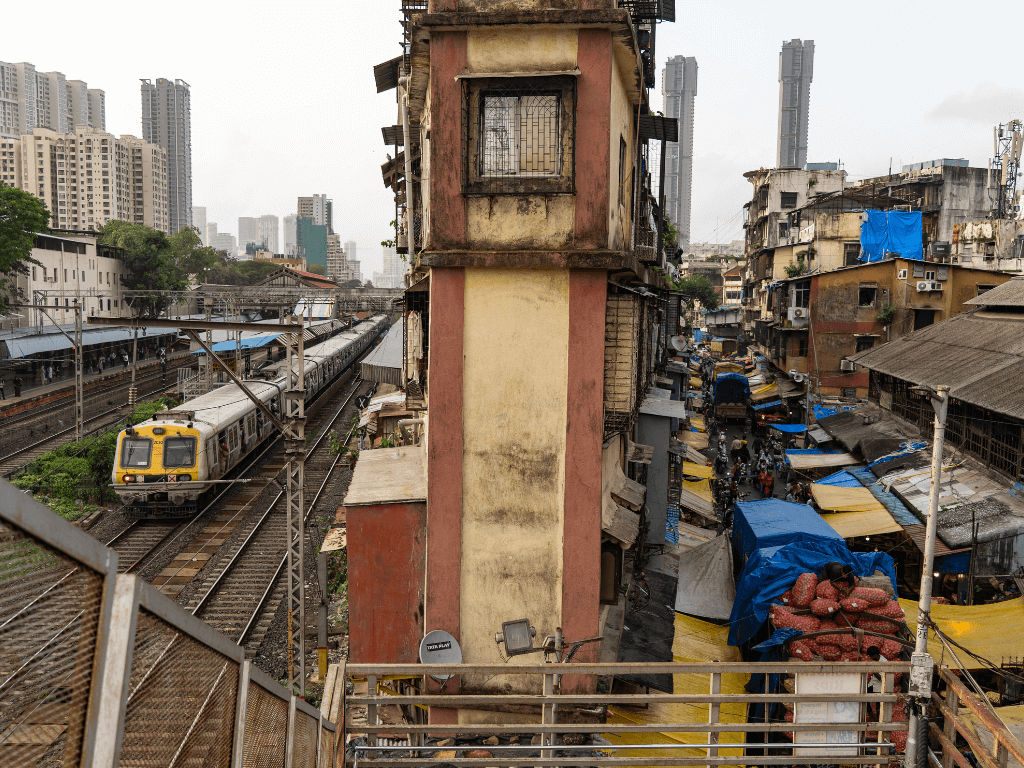

Density, you could say, is Mumbai’s calling card, the outcome of how its land use policies have shaped the city and influenced people’s lives. It may not be immediately apparent but land use and its impacts are everywhere—in buildings too closely situated in small precincts, apartments that look into each other, slums packed like sardines in a can, lack of open spaces, erosion of green areas and natural habitats, crowds of people everywhere, vehicles clogging streets. The jostle is evident in the photograph above.

Mumbai’s built up area doubled from 173 square kilometres in 1991 to 346 square kilometres in 2018.[1] However, this does not indicate proportionate or equitable land use. Nearly half the city’s population continues to live in slums but slums occupy barely 8 percent of the city’s land.[2] The redevelopment of slums and rehabilitation of slum dwellers from the inhospitable conditions has not meant an improved quality of life for most, again, because land use policies have allowed the Slum Rehabilitation Authority buildings to be on the least possible part of a plot on which the slum stood.

Land-use policies have also impacted the natural areas. The expansion of urban areas in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) by 4.5 times between 1972 and 2011, according to this IIT-Bombay study, meant “…the establishment of industries led to dense urbanisation along the Thane creek, where foothills were cut, and low-lying marshy lands have been filled up. This conversion of wetland to built-up areas in many parts of Mumbai has impacted coastal ecology, the gravity of which needs to be studied.”[3]

The impact of land use is discernible not merely in density of buildings but in the lack of space for people in public transport such as trains and buses, the jostling of markets and pedestrians outside each of the 150 suburban railway stations, traffic congestion on its arterial roads, the absence of adequate play and recreation spaces, the congested living spaces, and so on. When I, Aniket, set out to shoot photos for this photo essay, I realised that land use and density reflects in so many ways from the high rises of south Mumbai to the slums in Kurla and Asalpha, through Google Maps and the people I met on the way; their contours and meanings constantly shift across the city.

Gentrified dense Parel-Lalbaug as seen from the flyover: Mumbai’s Lalbaug is famous for the Lalbaugcha Raja and its old chawls. It reflects the rapid and haphazard construction and redevelopment across the city. At least 31,000 redevelopment proposals were approved as of May 2024 which is close to 40 percent of the city’s housing projects.[4] But Parel-Lalbaug, where every possible inch of land has been built upon, represents the lost opportunity for rational and people-oriented land use.

Slumdwellers compressed into minimum land, seen from Asalpha: Tiny and under-serviced rooms rise as slums along the Ghatkopar hill in eastern Mumbai, exist cheek-by-jowl with the city’s first metro line. These are visible from the aircraft as they come in to land at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport a few kilometres away. A study by German post-doctoral researcher John Friesen, in 2024, found that the percentage of land occupied by slums in the city reduced from 8 percent in 2005 to 7.3 percent in 2022 while the number of high-density settlements and tightly-packed slums increased from 988 to 1,359 in the same time period.[5]

Density does not improve with redevelopment: Tagore Nagar in Vikhroli represents the city’s defining characteristic: both slums and redeveloped buildings densely situated with barely any room between two structures. These ‘vertical slums,’ as the Bombay High Court termed them,[6] have not provided more space or amenities but have exacerbated people’s pre-existing problems, especially of health, while disrupting their social relationships. Importantly, the Development Control Regulations for rehabilitation buildings has meant insufficient light and ventilation on the lower floors which, this study[7] in M-East ward, closely associated with the incidence of tuberculosis. It recommended ‘better planning and architecture measures to improve housing and avert a public health crisis.’ Land use policies, clearly, have led to adverse impact on health.

A child’s delight despite the dark dingy corridors: This portrait is emblematic of the inner areas of almost all redeveloped buildings where residents suffer the lack of light and ventilation. Situated near Cotton Green railway station, this MHADA Colony has buildings stacked so close to each other that dark corridors are the only play spaces available for children. Most buildings in Mumbai do not have open spaces for children to play but the redeveloped buildings with super-high density are, by far, the worst.

Studies show that play[8] is central to every child’s development and well-being, to build relationships, develop leadership skills, and navigate social challenges. Architect, activist and designer Martina Maria Spies told Question of Cities in this interview[9] that “…because play is constantly being pushed to the margins in our urban environment, in the blind pursuit of infrastructural progress, we have pushed out all the open spaces, empty spaces, green spaces from our urban narrative.”

Shameful that they are forced to play this way: In Jijamata Nagar, Kala Chowki in south central Mumbai, a bunch of children find less than half a cricket pitch to play their favourite game as Raj Thackeray looks down from a political poster. In the midst of old chawls that somehow accommodate living spaces, parking spaces and storage spaces, children have to make do with leftover spaces for play. How many open spaces, play areas, neighbourhood parks and maidans are in an area is not accidental but the outcome of land use plans and policies. Poorer areas have fewer of them.[10] The race to build more is stealing children’s future.

Senapati Bapat Marg at Dadar densely packed with street vendors, buyers, pedestrians and vehicles: Everyone is at their wit’s end here and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation periodically evicts street vendors to ease the congestion. This too is an outcome of land-use planning and development plans that ignore the existing realities of street vendors, in fact, of all types of informal economies that keep the city going. Mumbai’s planners and agencies have largely approached planning as a top-down office-based and bureaucratic exercise rather than a people-led and dynamic one.

Dadar’s Parsi Colony, one of the six-odd precincts built with town planning norms, an enduring lesson in land use: A stone’s throw away from the bustling Dadar station is the 105-year-old Parsi Colony built in the wake of the bubonic plague. The layout prioritised people’s well-being with low-rise buildings, several large gardens across the neighbourhood, open areas between buildings, abundant space on roads and pavements. The Bombay City Improvement Trust, set up in 1898 to decongest the city, procured 440 acres of land in the then suburbs for well-planned neighbourhoods.[11] The land use lessons that Bombay learned then have been lost on Mumbai’s authorities now.

More of the same: At Worli Naka, the century-old Bombay Development Department (BDD) chawls, the low-rise corner structure seen in the foreground, are now slated for redevelopment. Built in the British era to house the port and dock workers,[12] the nearly Rs 11,000-crore redevelopment project helmed by MHADA will replace the 121 low-rise blocks with 33 towers, each of 40 floors, to house the residents alongside 10 new towers, each with 76 floors of well-appointed apartments, to be sold in the open market. The ensuing density will repeat that of the under-construction buildings seen at the back of the frame. Even when there’s an opportunity to reimagine and revise land use for better living conditions, Mumbai’s authorities seem to let it pass.

A picture of wilful neglect that forces millions into unsafe spots: This ‘bus stop’ at Bhandup, like hundreds across Mumbai, is an apology of what should be. With a mere pole and placard of bus routes listed, BEST commuters, who number nearly 3.3 million a day, are forced to wait on roads or edges of pavements, jostling for standing space amidst shoppers. The BEST bus service is being bled to a slow and systemic death[13] but this state of bus stops is equally an outcome of land use allocation that overlooks or neglects the needs of public transport and its commuters. The chaos and unsafe conditions are not incidental.

The metro is a neighbour: A residential building situated so close to the DN Nagar metro station that there’s hardly any breathing room or privacy left. Mumbai’s land use policies and development control regulations have determined how much space is needed per capita for living – a measly 5 square metres for a person – but there was no measure of how much external space for roads, amenities, open areas would be needed for a dignified life.[14] Insensitive land-use plans have meant haphazard development such as this one which would not have been allowed in major cities of the world.

Every inch of space occupied: With 2,450 vehicles per kilometre of road space, Mumbai’s congested vehicular population mimics its buildings and people. In 2024, an average 193 cars and 460 new bikes were registered in Mumbai daily.[15] Private car parking, seen here in Byculla, has turned out to be a vexed issue with cars occupying space around buildings, on pavements, and on streets leaving little for people’s movement and other activities. The BMC’s parking policy, ironically, threatens gardens and maidans as well as open spaces in housing complexes – another manifestation of warped land use.

Mumbai there was at the bottom right and Mumbai being built at the far end: From Worli Koliwada, one of the city’s oldest settlements of fisherfolk, the two Mumbais are unmistakably stark and could not be different. The informal settlement of Koliwada is densely packed but, within it, has room for interpersonal interactions, fish sorting and drying activities, weaving and repairing of fishing nets. Self-sufficient areas such as this, like Dharavi too, are giving way to stand-alone closely-situated tall towers or gated communities. It’s not only the density that matters but its impacts on people’s health and well-being, and its lasting impact on ecology.

Mumbai’s lack of space is often the target of jokes and memes. It is also a continuing lament of many in power. That the city has only 437.7 square kilometres of land is cited as the excuse for the shortage of land for affordable or public housing and deplorable lack of amenities. However, as these photographs show, it is not only the land or developable land available but how it is utilised, through deliberately-made plans and policies, that determines the nature of the city and the quality of life of its millions.

Aniket Gawade is a Mumbai-based photographer whose work predominantly focuses on issues surrounding marginalized communities. An engineer turned photographer, Aniket currently works in the development sector documenting various topics around the domains of environment, education and healthcare.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Cover photo: The optimum utilisation of space in Mumbai, as seen from the Byculla station foot over bridge.