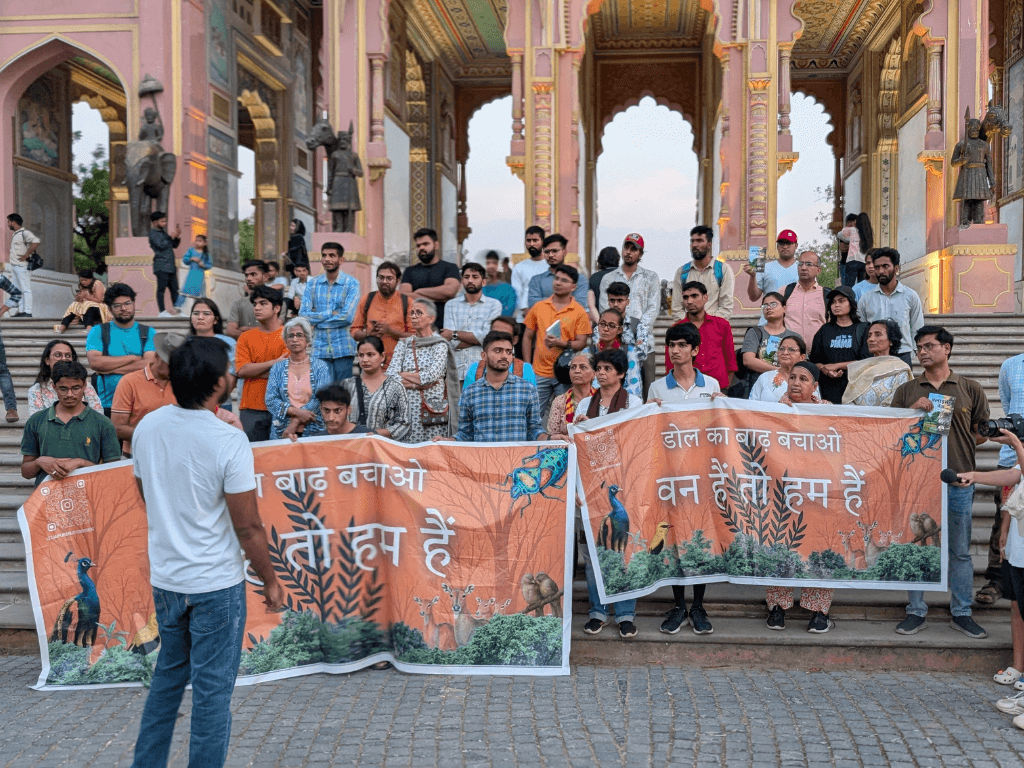

“The forest spoke, and we answered,” reads an Instagram post[1] by ‘Save Dol ka Badh forest’ account. And, for over four years, Jaipur’s residents answered with pleas, protests, dialogues finally snowballing into a movement to save the forest in the heart of the Pink (and hot) City. Their campaign and the issue itself have flown below the radar at the national level, not getting the headlines like the Hyderabad forest clearing had.[2]

Dol ka Badh is a 100-acre forest at Taron ki Khoont, right in the heart of Jaipur, the city in the Aravalli range that routinely sees summer temperatures of above 40-42 degrees Celsius. Every metre of green and every tree can help regulate the temperatures. With the Dravyavati River flowing quietly beside it, the Dol ka Badh, though located next to Sanganer and Mansarovar industrial areas, is the only green space for several kilometres in the southern part of the city – the city’s green lung and a crucial buffer zone.

Unmindful of this, the Rajasthan government green-lit an old plan to hack down the Dol ka Badh to, predictably, make way for development which means construction. The plan by the Rajasthan Industrial Development and Investment Corporation (RIICO), includes the PM Unity Mall, a fintech park, residential complexes, hotels, and a Rajasthan Mandapam. On September 11, RIICO signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the state-owned National Buildings Construction Corporation (India) Ltd to develop projects currently worth around Rs 3,700 crore.[3]

Photo: Save Dol ka Badh Collective

Jaipur’s citizens had no option but to fight back to the best of their abilities for the past four years but their campaign gathered momentum this year. “Dol ka Badh is a natural ecosystem. The trees here are native and not planted by anyone. The huge number of birds here shows the rich biodiversity of the place,” says Shaurya Goyal, a mechatronics engineer-turned-entrepreneur who was among the first responders when bulldozers ploughed into the forest in 2021. From college students to working professionals and senior citizens, the movement has drawn different kinds of people united by their determination to somehow save the Dol ka Badh.

The movement has sustained, so far, in the face of challenges. But the message should have been realised by RIICO and the state government. Instead, they resolutely justify hacking the forest on the grounds that it was not always a forest because it grew over the past 40 years on land meant for industrial activity that was left barren. Do the antecedents matter or the fact that Dol ka Badh is not a fully-grown forest with hundreds of trees and rich biodiversity?

The critical cooling and cleaning role

The urban forest plays a significant role in warding off the urban heat island effects in Jaipur; preserving it is a way to keep the city cool. Jaipur’s temperatures can soar to an unbearable level – and the highs are rising. It was 43.5 degrees Celsius this April 18, the highest temperature recorded in April since 2018.[4] The India Meteorological Department, this May 21, recorded a scorching 44.8 degrees Celsius.[5] Also, in May, the city’s minimum temperature of 32 degrees Celsius was 4.3 degrees above normal which meant nights becoming warmer and offering little relief from the day’s highs.[6]

Last year, on May 20, the city recorded the highest temperature at 45.9 degrees Celsius – 4.3 degrees Celsius above normal and the highest since 2015.[7] In 2022, on May 3, the city’s highest temperature was 45.4 degrees Celsius.[8]

There are no studies on the causation between the summer temperatures and the extent of green areas in Jaipur but correlations can be drawn. Without the 100-acre forest and its over 2,400 trees, Jaipur would have had blistering heat. It also helped regulate air pollution which is a rising concern – the Air Quality Index of 235 in November last year made Jaipur the second highest polluted after Delhi.[9]

The benefits of green cover[10] are numerous; the greater the tree cover, the healthier the city and its residents. “In the lush green Dol ka Badh, it’s about 2 to 5 degrees Celsius lower than the surrounding areas. We protested for 60 days sitting under trees and did not feel the heat,” Dhiresh Kumar Jain, an accountant who joined the movement six months ago, told Question of Cities.

From 2001 to 2024, Jaipur lost 4 hectares of tree cover, equivalent to 1.8 percent of the 2000 tree cover area[11] but, beyond the average, what matters to the people is the ground-level green that they can access. The city has a dismal 1.60 square metres per capita of open green space – a fraction of the WHO norm of 9 square metres[12] and a fraction of the green space in Delhi.

The distressing statistics should have meant even more urgency to protecting and preserving green patches like the Dol ka Badh and its biodiversity. A 2021 survey[13] found 2,421 trees of 30 different species and 54 types of shrubs and herbs in the Dol ka Badh forest[14] and 64 species of birds, both resident and migratory.

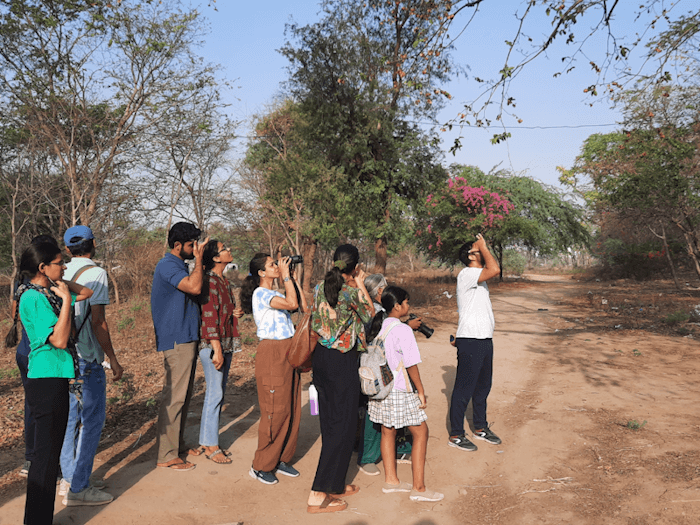

Photo: Save Dol ka Badh Collective

Forest (or not), citizens stood up

The argument that the forest did not always exist is specious, to say the least. It might have been vacant land handed over to RIICO in the 1980s for construction but, left to itself over decades, nature found a way to make its home there. The forest is as natural as any could be. In the 2020s, in the face of climate change impacts such as higher heat and floods, to cut it down in order to implement a 40-year-old plan is myopic.

In 2021, when the Rajasthan government renewed the plan to build a fintech park and earmarked the cutting of trees, five citizens, including Goyal, launched ‘Save Dol Ka Badh’ campaign. They organised nature walks and bird watching here to educate people about its importance and to connect with nature. When the people’s movement started, many were not even aware of the planned ecological destruction.

Savi Shekhawat was nine years old when she joined the movement to save Dol ka Badh four years ago. As she kept participating, her determination to save the Dol ka Badh grew. “I am sentimentally and emotionally attached to the movement,” says the 13-year-old who cycled from Jaipur to Delhi with her younger sister this August to canvas for the cause. “We were struggling to get support from people. I thought of going door-to-door and talking about our movement. And cycling, the eco-friendly way, was the best transport,” says Shekhawat, “We stopped in every town on the route, spoke to people about what was happening in Jaipur.” The siblings met residents of Kotputli, protesting for 985 days against a cement plant that has caused multiple diseases, and were energised.

All governments out to destroy, not protect

It was the Congress government in 2023 when the construction of the fintech park started. As the bulldozers began axing trees, the ‘Save Dol ka Badh movement’ intensified. Protesters sat or stood in front of the bulldozers to prevent them from touching the trees. Throughout each day, 30-40 people came in turns, found it “daunting and scary” but stood their ground.

“This went on for months. We reached a stalemate. Elections too were approaching. The contractor fled due to losses. The government had to put a halt to the project,” says Goyal. During the protests, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) supported the movement but, after winning the elections in 2024, “they are at the forefront of the construction. The BJP government scrapped the fintech park but announced a bigger project in Dol ka Badh,” adds Goyal.

According to government data, the area where the mall has been planned has only 48 trees but Goyal says the protesters counted 203 trees in 2025 and geo-tagged them. “The PM Unity Mall is being built where the forest has the maximum trees,” says Komal Srivastava, a social activist and an avid birder.

Photo: Save Dol ka Badh Collective

The citizens suggested alternatives – to transform the entire area into a biodiversity park and shift the projects to other locations, or build only the mall and turn it into a biodiversity park. Nothing cut ice with either of the governments. The Rajasthan High Court too dismissed their petition in 2023 – a setback for the group but they persevered with peaceful protests using social media.

“There’s going to be a mall and hotels. Doesn’t Jaipur have enough of them? We gave a good proposal to the government for a biodiversity park to conserve flora and fauna distinctive to Rajasthan, also develop a climate change laboratory,” says Srivastava. They even suggested a fee for the park since the government wanted revenue. “We studied models across the world and prepared this. We don’t have anything like this in Jaipur but the government wasn’t impressed,” he adds. The group then escalated the ‘Save Dol ka Badh’ protests this April with relay hunger strikes. The only response from the government was to detain them.

So far, at least 400 trees have been cut, they say. “We ourselves had counted the trees, and when the officials marked them to axe them, we were in tears. Sitting on the hunger strike, we wept as the huge trees were axed one by one, watching helplessly. If we don’t value the environment, we will face the effects of extreme weather,” says Mahima Chopra, a sociology student and active campaigner.

Photo: Komal Srivastava

The land is classified as non-forest land, so it falls under the Revenue Department, not the Forest Department. Dol ka Badh is right next to Dravyavati river and its natural water flow has been stopped after a high wall was built along the entire river. “The governments ruined this. Many water birds used to flock to the slope next to the river but their habitat is gone,” says Srivastava. There were around 20 antelopes; none were found after the noisy construction started. On a nature walk this October 12, a group saw utter devastation. “What was once so green did not have a single life, only machines all over,” rues Goyal.

Dhiresh Kumar Jain has used the Right to Information (RTI) route, demanding transparency about legal permissions to cut the trees. His numerous letters to officials, including the chief minister, and his meeting with ministers did not yield a single positive result – exposing once again the irrelevance that governments give to people’s voices. “In 2023, our delegation approached the National Green Tribunal (NGT), but its power is limited since Dol ka Badh is not a forest land. The NGT asked RIICO to first conduct an environmental assessment, which it did not; save as many trees as possible, and plant 10 more trees for every tree cut.”

Transplanting trees has been a failure. Last month, when Srivastava checked the transplanted trees, she found most of them withering. In Dol ka Badh, trees get ground water naturally through the river; besides, the authorities do not have the technology to transplant, she explains. “They transplanted 48 trees, including khejri, which cannot be transplanted,” adds Goyal. Although Rajasthan was the first state to table a Green Budget in March 2025 with a special focus on forest and environment, its decisions and actions – including the negation of people’s voices – has exposed its double standards. Like in Pune[15] and Hyderabad,[16] it is the people of Jaipur who have stood firmly by their greens, struggling but unwilling to give up the fight to save the forest they know.

As Devendra Bhardwaj, retired deputy conservator of forest and a resident of Jaipur, says: “It takes years for a forest to take shape. When there are trees, there will be birds, butterflies and other insects — whole biodiversity hub. Dol ka Badh is a huge ecosystem.” People know its value, governments do not.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with more than 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she writes about climate change and is learning about sustainable development. She was most recently a Fellow of the Earth Journalism Network working on the issue of Non-Economic Loss and Damage suffered by communities due to climate change in Odisha.