When the Mussoorie Dehradun Development Authority released the city’s Draft Master Plan 2041, in March 2023, it received almost a thousand suggestions and objections. Many touched upon the lack of green spaces.[1] This encapsulates the core issue around trees in cities: Development and master plans do not focus on trees to protect them or make a cursory mention in relation to other themes of ‘development’.

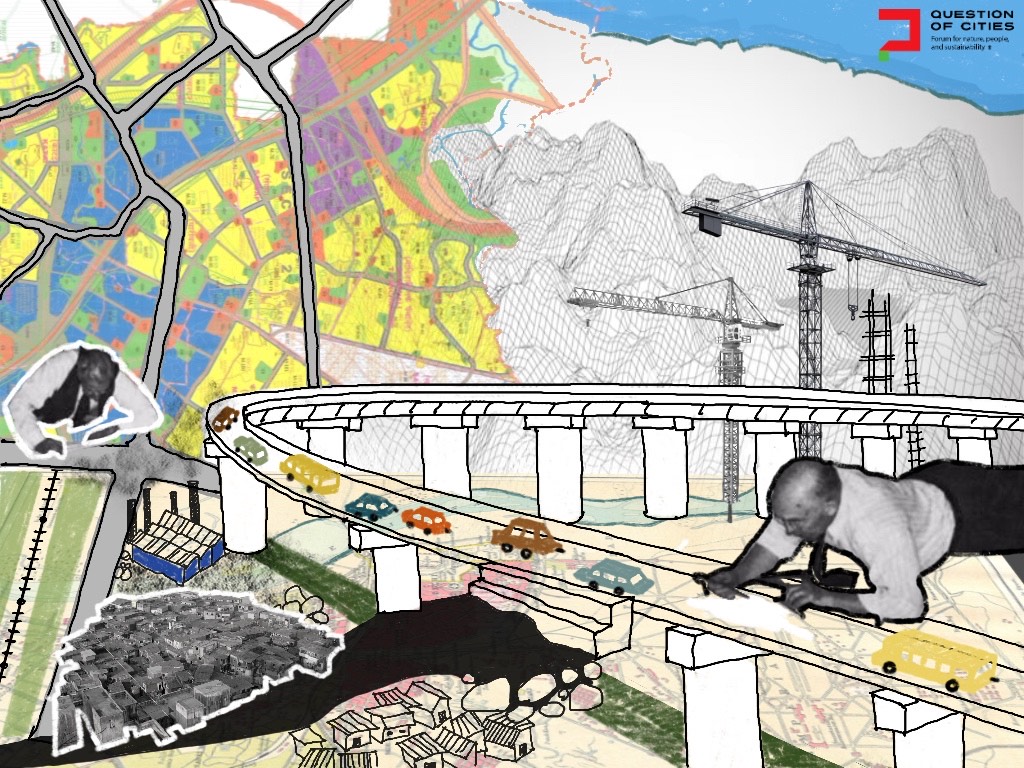

When plans make little to no room for trees, cities do not either. Trees are widely seen as dispensable, as impediments to ‘development’ to be hacked and axed when land is needed. Also, tree bases are concretised and policies on tree transplantation are missing. Are we surprised then that nearly every city in India has lost thousands of trees over the past few years as development picked up pace?

Planners, official and independent, may not be able to bury their heads in the sand and do business-as-usual any longer. Master plans, development plans, land use plans, heat action plans, climate action plans will have to acknowledge trees (and water bodies) as natural wealth of a city and draw up explicit policies to protect them as well as expand their coverage as part of climate resilience strategies.

The Dehradun Master Plan, for example, reads: “In 2000, the Ministry of Urban Affairs and Employment published guidelines for greening of urban areas and landscaping. The guidelines suggest steps for protection of trees and enhancing their lives while undertaking concretisation of pavements”. This is not enough. For a town once revered for its lush green slopes, Dehradun, like most cities with rampant development, is rapidly losing trees. Around 31,750 trees have been axed or are earmarked for axing in the last three years.[2]

The nub lies in the perception that development and tree cover are mutually exclusive; they are not. Tree cover can be maintained, even expanded, without compromising or reducing the development potential. Moreover, the mindset of developers needs to change that every inch of a plot must be built upon.

Failure of plans and laws

Urban development plans and master plans are largely confined to land use and land allocation; they earmark land or plots for use or construction and, thereby, steer the growth cities in certain directions. The question, especially in the times of climate change, is the redundancy of this approach. There cannot be plans for land use without factoring in climate change impacts such as heat waves, floods, poor quality air and so on.

Planning would have to be nature-based or nature-led. Plans would have to go beyond merely acknowledging natural areas – trees, hills and green areas, water bodies – in cities; they would have to be marked as eco-sensitive zones not to be opened for any construction, and make sound strategies to protect and preserve them while allocating land for development.

The laws on urban planning would have to be amended for this. In fact, laws and policies on urban forests and trees are far from ideal, as the report Regulating Urban Trees In India Issues And Challenges, by Manju Menon and Kanchi Kohli for the Centre for Policy Research,[3] found in 2022. “While urban access to clean air and water have become major concerns for policy planners, the importance and role of urban treescapes in Indian cities have not received sustained attention from these quarters. There are several research and advocacy organisations that study and comment on the legal and policy frameworks that govern forest conservation in agricultural and forest landscapes of rural India. However, relatively less is known about the policy directions and approaches adopted on urban forests and treescapes in India,” states the report.

The Maharashtra Regional and Town Planning (MRTP) Act, 1966, mandates that a development plan must indicate the use of land and designate open spaces, playgrounds, zoological gardens, green belts, nature reserves, sanctuaries; it does not, however, explicitly mandate their protection and conservation, or fix accountability. On paper, Mumbai’s Development Control Regulations (DCPR 2034), addresses tree plantation with provisions for enhancing, conserving, and preserving biodiversity, and asks that “if trees are required to be felled, twice the number of trees shall be planted” with prescriptions and calculations based on plot sizes.

In reality, this has been undermined by other ad hoc rules such as allowing private buildings to occupy the entire plot while plants-in-pots are placed on podiums of high-rises.[4]

This negates the purpose of trees and urban forests. As Shweta Wagh, Mumbai-based architect and urban researcher, rues, “It is clear that planning authorities lack the will to protect tree cover and attempt to remove the existing safeguards or reduce areas designated for conservation. Only legally designated forest and mangrove areas are zoned as ‘natural areas.’ There is no provision for a comprehensive mapping and recording of existing land-cover or tree-cover outside these legally protected zones.”

Tree protection or permission to cut?

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) of projects, especially mega infrastructure projects, is an important tool to save trees but it has increasingly become a box to be ticked off. Here’s the tree loss that was permitted for projects in only four cities:

- Delhi government gave permission[5] to the National Highway Authority of India to axe 6,600 trees to build a third ring road, though on the condition of transplanting them. As many as 40 big projects[6] in New Delhi were approved or constructed that required axing trees[7] after the transplantation policy of 2021 but the success of transplantation remains questionable.[8]

- Nagpur’s Inter-Modal transport project meant the axing of nearly 1,940 trees[9] – a disaster for a city that was once among the greenest[10] but lost as much as 40 square kilometres of its green to infrastructure projects between 1999 and 2018.

- Mumbai lost a staggering 40 percent of its green cover and 81 percent of open land between 1980 and 2018 even as it saw 66 percent rise in built-up areas, according to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan.[11]

- Bengaluru, once India’s garden city, lost 93 percent of its lake and forest cover to concrete and construction while construction increased by over 1,000 percent, found Indian Institute of Science (IISC) researchers.[12]

In 2011-12, Nagpur was the second greenest city in the country; it is now 28th in Maharashtra, says environmentalist Dr Jaydeep Das, “The garden department is basically a tree-cutting permission department. This is a big procedural flaw. The first thing should be how much green space does the city want to preserve and design accordingly but people come to the garden department for permission to cut trees after getting all other clearances and sanctions.”

The Jaipur Master Plan 2025 envisions sustainable development but, in 2021, the Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corp Ltd announced the setting up of a Financial Technology Park in Dol Ka Badh spread over 105 acres near Dravyavati river where the forest has around 2,500 trees.[13]

nature-based solutions.

Ways forward

It’s not merely the law; the implementation too leaves much to desire. In 1983, Rajasthan officially declared Khejri (Prosopis cineraria) as its state tree with restrictions on chopping it; these trees were already protected under previous laws but more than 10,000 trees are felled every year[14] because of ineffective enforcement. There are clear ways forward:

The implementation can be stronger if the planning process is thorough on the green cover in cities, say experts. Plans go between architects, civil engineers, and consultants, many of whom do not factor in the ecology; the garden department or horticulture department is brought in at the end of the approval process. The way to make space for trees is to include them right at the beginning and “that must be completely non-negotiable,” says researcher Vallari Sheel, “Trees are as important as flyovers and buildings. While building infrastructure, we must make space for trees.”

What cities need: Master plans must factor in trees and make space for them especially now that trees are acknowledged as effective nature-based climate solutions. “At each project level, we need to enforce the process. When you apply for project approval, you need to submit a tree site map, demonstrate how trees on site will be saved, and how the impact on trees will be minimised,” says environmental analyst Chetan Agarwal.

Many cities have versions of Tree Protection Act and various kinds of Tree Authorities but, evidentially, these have not been sufficient. As the CPR report points out, this is partly because the scope of work and responsibilities of Tree Authority differs from city to city as do the fines and penalties. “Only in two states out of four where the law requires the constitution of tree authorities, do the laws specifically prescribe the role of tree preservation to them,” it points out.

Tree Authorities slip up on one mandatory aspect – carrying out regular tree censuses. Without this, it is difficult for people to track how many trees have been lost, which axed, and how many transplanted ones survived. As Agarwal says, master plans by themselves do not protect trees. These have to be backed by regular tree census, restrictions on cutting, marking green belts that cannot be touched, clear policies on transplantation and so on. “The master plans do not define the area of a park or width of a green belt. This layout planning is done at levels below that of the master plan,” he says. For this, tree census is essential.

What cities need: A Tree Authority must account for all the existing trees, on a plot-by-plot basis, and these tree maps must become the basis for the building proposals departments in civic bodies to grant approvals. The tree census in a city must be done with people’s participation.

Other plans such as Climate Action Plans or Heat Action Plans do factor in green cover but many are not notified which means their implementation is no one’s responsibility. As environmentalist Stalin D says, the Mumbai Climate Action Plan (MCAP), without notification, is a wishlist; it recognises that certain areas are losing tree cover making them vulnerable to rising temperature but its recommendations are not mandatory and do not reflect on ground yet.

“Everybody agrees we need more trees, so the authorities also say we need more trees. But there are no restrictions on cutting them,” remarks Stalin. Like many others, architect and planner Rohan Chavan questions the process of drafting a development plan without synchronising it with other climate-specific plans. Delhi’s Master Plan is still awaiting notification.

What cities need: Where master plans or development plans have been notified, they must be synchronised with specific plans such as climate action plans and heat action plans which talk about the need for trees and green cover as a part of climate resilient strategy. The climate-related plans must be mandated too – sooner than later. In cities where master or development plans have not been notified or mandated yet, they must be revised to factor in green cover and trees in a non-negotiable manner and as a part of climate resilient strategies.

There is growing interest in greening a city with practices such as the Miyawaki technique and roof or terrace gardens. The Japanese-inspired Miyawaki forest has become a buzzword with city governments eager to commission specific projects to rapidly ‘green’ an area for carbon sequestration.

However, as Shweta Wagh suggests, a science-based approach to tree conservation and planting is called for because “although the Miyawaki technique emphasises plant density, it fails to allow the natural maturation of many species of larger trees that may have wider or spreading canopies, and may inhibit their ability to sequester carbon efficiently.” Similarly, while roof or terrace gardens in many international cities have brought in welcome whiffs of green, they do little for the complex ecosystem that trees on the ground support. Yet, another approach in cities like Mumbai is community projects to green an area which, though welcome, “should not remain piece-meal initiatives driven by NGOs and community-based organisations,” Wagh suggests.

What cities need: Given that trees and green cover in cities are increasingly seen in terms of climate resilience, there must be plans and policies reflecting this aspect. Small community initiatives must be scaled up especially in informal settlements which, studies show, have fewer green spaces and, correspondingly, higher levels of heat and pollution. In Mumbai, Stalin suggests that the 24 ward officers – the city has 24 civic wards – must ensure that the area in their jurisdiction have at least 30 percent tree cover. “They should have the power to strike down a construction proposal if it is taking away the greenery,” he says. NGOs and voluntary groups must be given the right to monitor the green areas in their neighbourhoods.

Why trees?

India has around 16 to 28 trees per person, depending on diverse calculations of urban areas and forest cover but both these are relatively low compared to global averages. Greenland, for example, has 4,964 trees per person while New York, Los Angeles, São Paulo, Tel Aviv and Paris do well on average. India’s State of Forest has turned controversial now with many pointing out lacunae and gaps in its assessments which show a modest rise in green cover but it must be remembered that cities need a separate assessment.[15]

India’s cities would do well to take a leaf out of Barcelona’s experience. In the second largest city in Spain, major climate challenges amidst shrinking green spaces prompted city planners to draft ‘Trees for living: Barcelona Tree Master Plan 2017-37’ to maximise environmental, social and economic benefit from trees.[16]

How we see trees in cities is, after all, a matter of perception. As Rohit Majumdar, a professor and researcher at Mumbai’s School of Environment and Architecture, studying Adivasis in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, told QoC: “When I asked elderly Adivasis about the changes in their forest, I was always corrected, ‘What you call forest is our garden’. There is a big learning here: Modernist planning vocabularies work with dualism of forest/city, land/water. Interrogating such dualism should be the first unlearning in urban planning education.”

Trees ought to be everywhere around us even in cities, not merely in designated places or secluded forests. Trees are our sustenance, after all.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about climate change and is learning about sustainable development.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award consecutively in 2023 and 2024, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.