Citizenship is most commonly understood as membership in a political community and the legal relationship between an individual and the state. But the idea of citizenship also entails normative ideals – of exercising rights and participating in public affairs. Historically as well as in modern times, the city has been a key site where various notions of citizenship are claimed and contested. However, the idea of citizenship is increasingly under challenge in India today. At one level, laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, raised concerns about how the legal status of citizenship is determined. At another, the right to live with dignity is being challenged by coercive state actions like the summary demolition of houses of minorities and political opponents. Hence, both formal and substantive aspects of citizenship are under threat.

In this context, it becomes important to understand what the idea of citizenship means and how it can be employed for claiming and exercising rights in Indian cities. Since much of India’s urban population works in the informal sector and lives in informal housing, how can urban inhabitants exercise citizenship and claim their rights in the city and Right to the City? This essay seeks to examine the meaning and evolution of citizenship, discuss its practice in everyday urban life in India by making claims on housing, explain how a retributive state is now undermining these claims, and explore what notions of citizenship can counter these challenges.

The idea of citizenship

The word “citizen” is etymologically derived from the Old French word citeien[1] and its variations that mean “city-dweller”. The idea of citizenship has been closely associated with the city since it referred to the rights a “freeman” possessed to participate in the affairs of the city-states in ancient and medieval Europe. Along with rights, a free citizen also had a set of duties, especially linked to the ideas of “civic virtue”. For Aristotle, since “man is a political animal”, citizenship involved actively taking part in the public affairs of the city-state ‒ to rule and be ruled. While civic participation in government was central to the Greek view of citizenship, Roman citizenship laid more emphasis on the legal relationship of the citizen and the State. Over time, the power of the city was subjugated as the nation-state became the centre of political authority and the default unit of citizenship.

Photo: Sahil P via Twitter

In modern times, the most influential work on citizenship is T.H. Marshall’s seminal essay “Citizenship and Social Class”[2] originally published in 1950. Marshall identified three key elements or spheres of citizenship: civil, political, and social. The civil component refers to individual rights like the freedom of speech and association, and the right to property. The political aspect refers to the right to participate in public affairs like the right to vote and contest for elected office. The social aspect refers to the right to welfare and right to live the life of a civilised being. Marshall’s formulation is primarily a liberal framework of citizenship since it is framed as a set of rights and corresponding duties that an individual has in relation with the state.

In her seminal book, “Citizenship and Its Discontents”[3], Niraja Gopal Jayal explores the evolution and contestations over citizenship from colonial to post-independent times in India. It examines citizenship from three perspectives: as legal status, as rights, and as identity, and the relationship between them. Jayal highlights that while India instituted formally inclusive legal rights regarding citizenship in the Constitution, provisions for social and economic rights and its realisation have been weak. The presence of formal rights in law is not sufficient for citizens to be able to exercise substantive citizenship. Given the high level of inequality in Indian cities, the primary challenge of citizenship is to ensure that all inhabitants are able to translate their formal legal rights into actionable socio-economic and political rights.

Over the years, the Supreme Court of India has expansively interpreted the fundamental rights under the Indian Constitution to hold that the right to life means the right to live with human dignity which includes entitlements like food, clothing, shelter, education, and health. Since 2004, India enacted a set of legislations that guaranteed welfare rights like the right to education, work, and food.[4] Such legislative measures sought to bridge the gap between formal citizenship based on mere recognition of legal status and substantive citizenship that translates it to enforceable rights. However, since 2014, both formal and substantive dimensions of citizenship seem to be under threat in India. In a reassessment of how citizenship has evolved[5], Jayal notes that all three notions of citizenship- as status, rights, and identity- are increasingly coming under challenge.

Exercising Citizenship by Claiming Housing

Citizenship is exercised not just through the invocation of formal rights and duties legally vested on an individual, but through various political practices that make moral – not just legal – claims on the state. The city is the key site where new ideas of “insurgent citizenship”, not based in law but on moral claims of residence, are claimed and exercised. For cities in the Global South with high levels of inequality, citizenship is often practiced through moral claims over the city’s land, housing, and basic services.

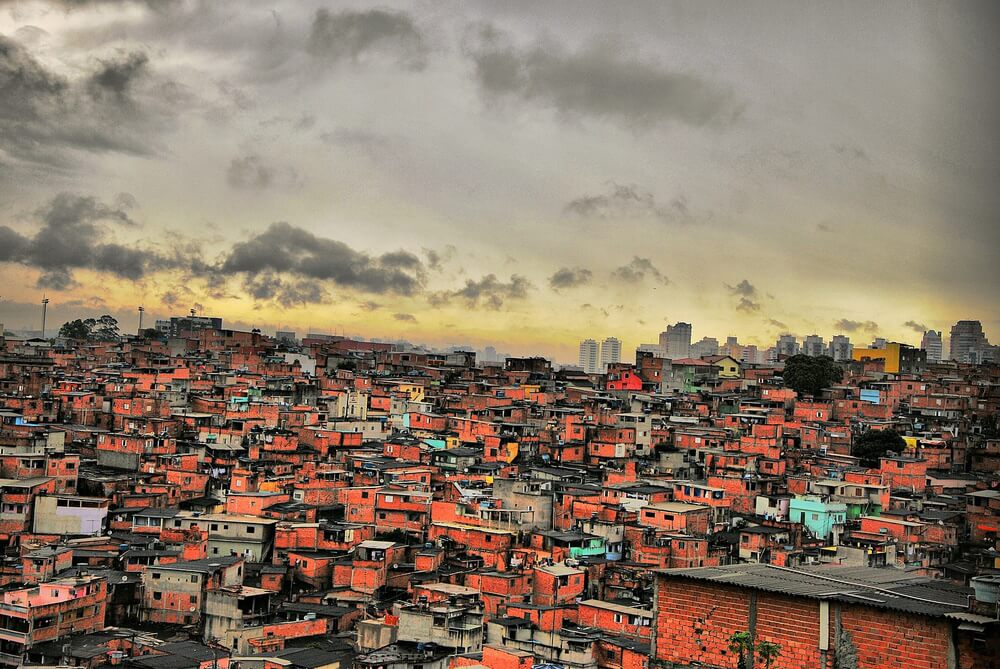

Anthropologists and urban studies scholars have examined how citizenship is an everyday political practice and mechanism for making claims on the state and other public authorities. James Holston argues that citizenship refers to a discursive relationship[6] to the state that is practiced through everyday performances of making claims. It is through practices of appropriating “the city’s soil through some form of illegal residence and demanding legalisation and legal access to resources” that the urban poor practice their rights of urban citizenship. Using the example of how the urban poor in Brazil make demands to legalise homes in urban peripheries, Holston argues how such “insurgent citizenship” challenges and expands the very notion of citizenship and rights.

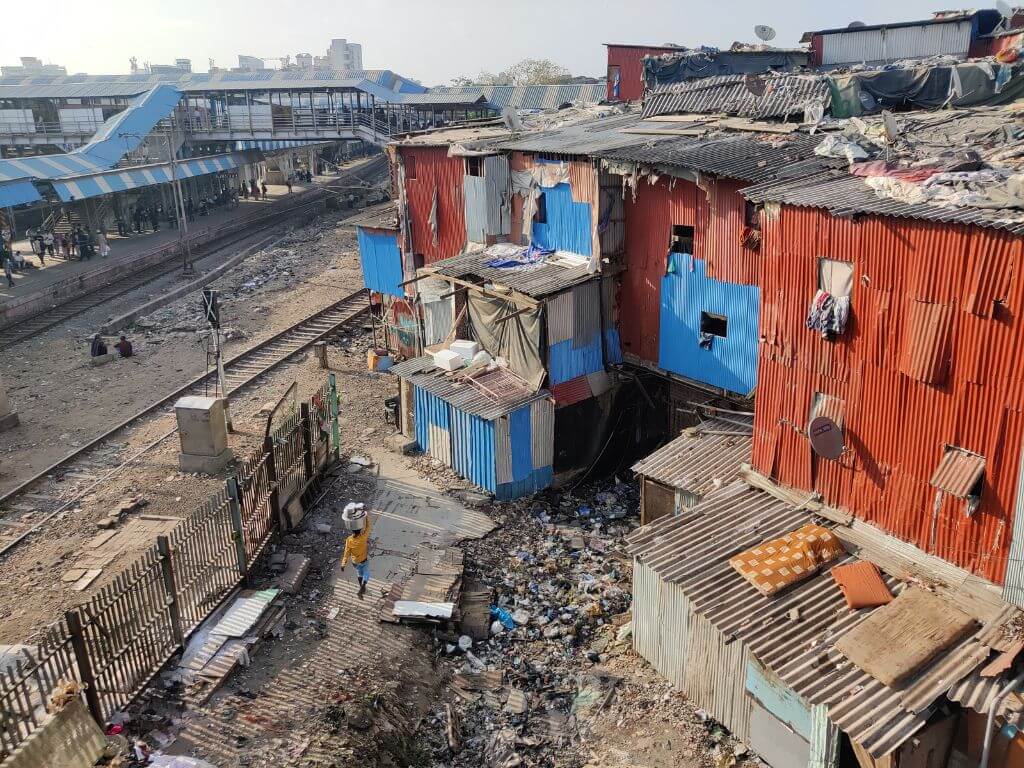

Photo: Creative Commons

In India, a high percentage of urban residents live in neighbourhoods that are not formally planned or approved by state authorities and hence operate in the realm of “informality”. Urban residents often attain their rights to inhabit a property not through clearly delineated legal procedures but through a series of political claims[7]. Poor groups often access empty and disused public lands, occupy them, build temporary settlements, incrementally obtain access to various urban infrastructure and services, and negotiate with political and bureaucratic operators to attain some level of legality. They work with elected councillors and the municipal bureaucracy to channel public investments into their informal settlements[8] through various informal tactics.

Such negotiated manner of accessing the right to inhabit and use urban space defy the liberal legal order of property rights and land-use based master plans. It is often through such political manoeuvres and negotiations that the urban poor gain access to the resources and services of the city. Exercising citizenship is, hence, not only about formally being recognised by the state or engaging in formal avenues for civic participation; citizenship is also about making claims to access, use, live and work in urban spaces through formal and informal means. Through such practices, the notion of citizenship itself is challenged, expanded, and arguably radicalised as it is defined by a moral claim for living and accessing the city, independent of the legal status of the claimant.

Slum demolitions and the retributive State

The political claims made on the city by the urban poor are, however, encumbered by its precarity. The gains made through everyday negotiations can be undone overnight by the heavy hand of the state, or even the judiciary. In fact, the judiciary has played a key role in the demolition of various slums[9] and informal settlements, especially in Delhi. In Public Interest Litigations (PILs) initiated by Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs) of middle-class neighbourhoods, the court often decided the case without hearing the slum-dweller and by merely relying on photographic evidence of the “public nuisance” caused by slums.

This trend of court-directed slum demolitions saw a reversal with the Delhi High Court laying down– in Sudama Singh v. Government of Delhi (2010)[10] and Ajay Maken v. Union of India (2019)[11]– that no authority shall carry out eviction without conducting a survey, consulting the population that it seeks to evict, and providing adequate rehabilitation for those eligible. However, these protections are now being dismantled by a new regime of government-directed slum demolition drive across various cities, primarily targeting minorities[12] and political opponents.

Last year, state authorities demolished homes of Muslims who were allegedly involved in communal clashes in Khargone in Madhya Pradesh and Khambhat in Gujarat. Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh saw the targeted demolition the house of Javed Mohammed, a social activist, after communal clashes broke out due to religiously offensive remarks made by two BJP spokespersons. Muslim homes and shops in Jahangirpuri in Delhi were also demolished, till the Supreme Court intervened to stay it. Before the demolition of houses in Khargone, the Home Minister of the state announced at a press conference that “whichever houses were involved in stone pelting, we’ll ensure they are turned into piles of stones themselves”.

Such statements indicate how the state is acting in a retributive manner to impose collective punishment[13] upon whole neighbourhoods, demolishing dwellings as ‘punishment’. This was institutionalised in Uttar Pradesh with the enactment of the “Uttar Pradesh Recovery of Damages to Public and Private Property Act, 2020” passed in the wake of protests against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019. The UP government has passed orders under this law to recover damages from people who participated in protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act.

Demolition of houses has now become a public spectacle that is celebrated by sections of the general public. Though initially targeted at minorities, the use of the bulldozer as an instant form of punishment is now meted out to anyone the state finds difficult to deal with or to satisfy public sentiments.[14] The seeming normalisation of the use of brute state power to quell dissidents and inconvenient citizens raises troubling questions. Such retributive violence inflicted by the state are antithetical to any democracy and negates all ideas of citizenship.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Citizenship as meaningful engagement

Even if we disregard the retributive and prejudiced nature of the state’s action, the summary demolition of houses ignores the due process of law and violate principles of natural justice. Regardless of the legality of any building, no public authority can carry out demolition without due process which involves giving the affected person a chance to be heard. In the landmark judgment Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985)[15], the Supreme Court held that Right to Life includes the right to livelihood and housing, and recognised that all citizens have a right to notice, hearing, and rehabilitation before being evicted. These principles have been upheld in subsequent cases that have further affirmed the right to housing in India.

While upholding the right to housing, the Court in Ajay Maken invoked the “Right to the City”[16] and relied on international conventions and judgments to expand the protections against eviction. The “Right to the City”, a radical idea of urban transformation conceptualised by sociologist Henri Lefebvre and popularised by David Harvey, indicates the right of all urban inhabitants, not just citizens, to participate in and appropriate urban space. It refers to the collective right of all urban inhabitants to have a role in decision-making regarding the city and the ability to access, occupy and use urban space. Hence, it breaks the legal formalism associated with citizenship and housing, and formulates a new idea of citizenship that recognises the rights of urban residents based on inhabitance and participation in the quotidian practices in the city.

The Ajay Maken case relied on judgments of the South African Constitutional Court like Occupiers of 51 Olivia Road, Berea Township v. City of Johannesburg[17], to hold that any person who is to be evicted should have a right to “meaningful engagement” with any relocation plans. The South African Constitutional Court had ordered that the local government and informal residents of Johannesburg engage in a meaningful dialogue which enabled the parties to reach an agreement that ensured protection against eviction. Similarly in Delhi, the Court facilitated the drawing up of a Draft Protocol for rehabilitation after consultative engagements with all key stakeholders including the residents who were evicted.

Such actions offer a unique form of decision-making whereby the Court is transformed into a deliberative democratic space where a meaningful dialogue is facilitated. Decision-making processes based on a meaningful engagement with all stakeholders, whether facilitated by the Court or any other public authority, furthers the idea of citizenship. As discussed earlier, the idea of participating in the public affairs of the state has always been central to the idea of citizenship. However, this need not be in the form of civic participation through formal institutions, where it is often the middle and upper-class residents who participate.

Substantive citizenship also means ensuring affected parties of administrative actions of the state get a chance to participate in decisions that affect their rights. Such forms of meaningful participation in decision-making processes protects the rights of all citizens, especially the most marginalised. At a time when the state is unleashing its might upon certain sections of society, it is important to demand and exercise the procedural rights of the due process of law as well as the substantive rights of social citizenship.

Mathew Idiculla is an independent legal and policy consultant based in Bangalore and a visiting faculty at Azim Premji University. His work focuses on issues concerning cities, local governance, and federalism in India. He has engaged with the field of urban law and policy for over a decade through academic research, legal consultancy, public advocacy, and popular writing.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey