Call this a macro-level coincidence or a part of a grand design. In 1991, as India was pushed to adopt economic liberalisation and privatisation as a way out of its forex crisis, the World Bank came out with not one but three flagship strategies for urban areas that would shape cities across the world.[1] Two of them focused on strategies for urban growth and linked it to land use, regulations, zoning and so on. Density, till then a word tossed around in architecture colleges and planners’ cubicles, was offered as the doctrine that could transform urban economies, especially in cities of the Global South. Over time, it became an ideology followed by many.

The World Bank’s strategy document Cities in Transition in 2000 “highlighted the effects of urban transformation and flawed real estate policies on land use and housing investments, with major ramifications for households, businesses, and nations” and Systems of Cities in 2009 “emphasised the importance of helping cities update their urban planning regulations so that they can manage higher population densities and prevent demand for scarce housing and land from bidding up prices excessively. Over time, the World Bank strategies increased their focus on issues related to land administration, land-use planning, and land development as fundamental building blocks for managing urban expansion,” according to its published records.[2]

The World Bank gave cities a new way to see themselves in the context of economic growth and land use. To paraphrase, it advocated that “economic growth will be unbalanced but development will be inclusive” if cities transform themselves along three dimensions of “density, distance, and division” essential for economic growth and development – higher densities as cities grow, shorter distances as workers and businesses migrate closer to density, and fewer divisions as nations lower their economic barriers to join the world markets.[3]

This was contained in the World Bank’s title Reshaping Economic Geography but it essentially sought to remodel cities through the economic growth path. And urban density was quietly made the norm. By 2017, the World Bank was convinced of its own supremacy in the subject and high density as a desirable objective. Its urban specialists stated: “High-density cities allow industries to flourish through processes of sharing, matching, and learning that could not happen as efficiently at a smaller scale…While the benefits of dense cities are widely recognised now, the policy dialogue on this topic was not always so positive. But in 2009 the publication of the World Development Report on Reshaping Economic Geography[4] helped to change attitudes.”[5]

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was not far behind. Its mission was to “encourage the expansion of trade and economic growth”[6] and this shaped several cities in the developing countries. The United Nations too joined the chorus on high density cities. The World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities, by the UN Habitat, mentioned implementing “policy measures that incentivise compact and moderate – or high-density development which allow more people to live in cities, while using less land. It is worth noting that significant spatial expansion is inevitable in these countries.”[7] It was a global monologue that density in cities, or high density, is good. The World Bank agenda had become the world’s agenda.

In India

India’s cities of the 1990s, then opening up to global capital, and under this influence willingly or otherwise embraced high density as the way forward. As the World Bank cemented its stance and doubled down in the face of criticism, large Indian cities did not look back. High-density cities became the default option of official planning and urban development, and has been endlessly – rather uncritically – repeated by a host of practitioners from urban planners and architects to policy makers and bureaucrats and, of course, the government of the day.

Sanjeev Sanyal, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the PM (EAC-PM), advocated for super dense cities and urged relooking at standards for building construction as recently as December last year. “India needs to relook urban design and create dense cities which fits our aesthetics, our way of living and are economically viable,” he had said, suggesting Indian urban planners should focus on building denser cities which monetise land, and do not occupy more farmland and forest land.[8]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In 2017, the Narendra Modi-led government approved the National Transit Oriented Development (TOD) policy and Metro Rail Policy,[9] encouraging the adoption of TOD as a key urban planning and growth strategy. With this, 27 Indian cities committed to building metro rail systems and many others to other forms of rail and bus-based mass rapid transit systems.[10] Not coincidentally, the World Bank has advocated TOD for some years before that “based on the premise that economic growth, urban transport, and land use can be managed more efficiently if planned together.”[11]

TOD integrates land-use and transport planning, allowing mixed-use neighbourhoods with frontages centred around public transport nodes. Urban planners advocate that TOD could address the twin problems of pollution and congestion by making urbanisation compact.[12] But this is easier committed than done – the central government is yet to implement the framework in 14 cities and despite 905 kilometres of metro rail network in cities across India, most have been unable to implement the TOD policy. Even in Delhi, the development along the metro corridors has been largely unplanned with poor access and last-mile connectivity – and, ironically, low density.

The Asian Development Bank has pledged USD 10 billion in June this year towards India’s urban transformation through metro expansion, infrastructure upgrades, and urban redevelopment in 100 cities.[13] These will include building walkable areas around transit nodes and creating mixed-use neighbourhoods, thus amplifying the TOD approach. High density, once again, is being unquestioningly promoted as a good approach to urban economic growth and reducing car usage. Meerut, in Uttar Pradesh, is among the first in India to integrate TOD into its 2031 Master Plan.

The point is not that density in cities does not bring benefits but rather that only one side of the density debate has dominated the discourse in governments, policy-making and the public all these decades. As the Congress on New Urbanism noted in 2023:[14] “When done well, density has much to offer. By bringing large numbers of people together, it can make public transit possible. It can help shops, restaurants, and other enterprises thrive. It can entice people to walk rather than drive to many everyday destinations. If dense development includes moderately priced or inexpensive housing, it can offset some of America’s mounting economic inequality. It also can reduce stress on the natural environment, by using resources more efficiently and emitting fewer greenhouse gases than sprawl does. But density, when it’s badly arranged, when it clusters only the narrowest range of income groups, household types, and economic activities, can be stultifying. Rather than giving residents multiple options, it constricts their daily experiences.”

This other side, when “density is done badly”, lies mostly unexamined or uncritically examined. It has consequences as Dr Ramanath Jha, former bureaucrat and now an urban researcher, pointed out in this paper:[15] “Western economists, social scientists, and urban planners have been robust advocates of urban density. The standout benefit, decidedly, is that urban density fosters economic growth…Over time, cities in the Western world have altered their policies about urban density. With the onset of the 21st century, New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco took an anti-density stand.[16] They decided to curtail the growth of their populations through tight zoning regulations. No such policy has been scripted in India despite urban densities that are much higher in its cities.”

The paper points to the pitfalls of blindly accepting the high density approach in India’s cities. “Excessive urban density begins to amplify its negatives. The Western emphasis on urban density was in a different context. Western cities today are losing population on account of low fertility rates along with an economic downturn. Unlike their Western counterparts, the big cities in India face rising economies and swelling populations. While the virtues of urban density are undeniable, we need to ask how much density starts becoming counterproductive,” it warns.

Why important to examine

Not just Meerut but a host of India’s cities have adopted the high density approach and, lately, the TOD route to urban development.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Mumbai was unsurprisingly among the first cities in India to adopt the high density approach. In the wake of India’s liberalisation, industry leaders under the aegis of Bombay First had the international consulting group McKinsey chart out the Vision Mumbai: Transforming Mumbai into a world-class city. “For Mumbai to become a world-class city, it must ensure that housing becomes more affordable, the rental housing market is resuscitated, land is developed in an integrated manner and the city housing stock is upgraded,” stated the report.[17]

Over the decades, despite adopting the high density model especially in redevelopment of slums and old buildings, most of this has not come to pass. Instead, there has been a ‘slummification’[18] or construction of ‘vertical slums’[19] as part of the redevelopment in which slum dwellers have been pushed to live in uninhabitable conditions with densely-situated ill-planned buildings.

The impact of density across different geographies of the city, including on people’s health and productivity, now raise serious questions about density and equality, or land use equality. Even so, potential TOD places have been identified as railway stations at Bandra, Dadar, Mumbai CST, and the soon-to-be-operational Navi Mumbai International Airport.[20] The state government has proposed an amendment to Mumbai’s Development Plan 2034 to accommodate TOD along the underground Metro 3 route. If this comes to pass, builders will get additional FSI to develop projects within 500 metres of the metro line and connect them with vestibules.[21]

Photo: Pixels

Delhi has a Master Plan though it is yet to be notified. It was tweaked in 2013 to ease height restrictions of buildings and permit developers to build more swanky high-rises.[22] Despite the city’s plan being unclear, Delhi’s TOD policy was notified in 2015 and revised in 2019.[23]

The Delhi Development Authority’s first TOD project at Karkardooma is likely to be completed by 2026 and will include high-rise residential complexes, commercial and office spaces, and public utilities in one place with easy access to multi-modal public transport[24] cementing high density as the norm. Dwarka ISBT, Aerocity ISBT, and Jewar International Airport are among the areas identified as offering high TOD potential.[25]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Kolkata has seen haphazard urbanisation over the years with parts of the city touched by the density and TOD agendas. “Transit-Oriented Development is a long-term development strategy to increase metropolitan regions’ quality of life. The Metro Rail Transit System (MRTS) is an integral part of the TOD plan and significantly impacts urban development. It is a crucial transformation parameter that influences the overall urban structure,” says the research paper, Rapid Transit-Oriented Morphological Transformations in Indian Cities: A Case of Kolkata Metro.[26] The New Town authorities have allowed a 10 percent increase in the Floor Area Ratio (FAR) for small plots measuring up to 3.3 cottahs (one cottah is 720 square feet in West Bengal) so that the square feet of the homes constructed on them can go up.[27]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

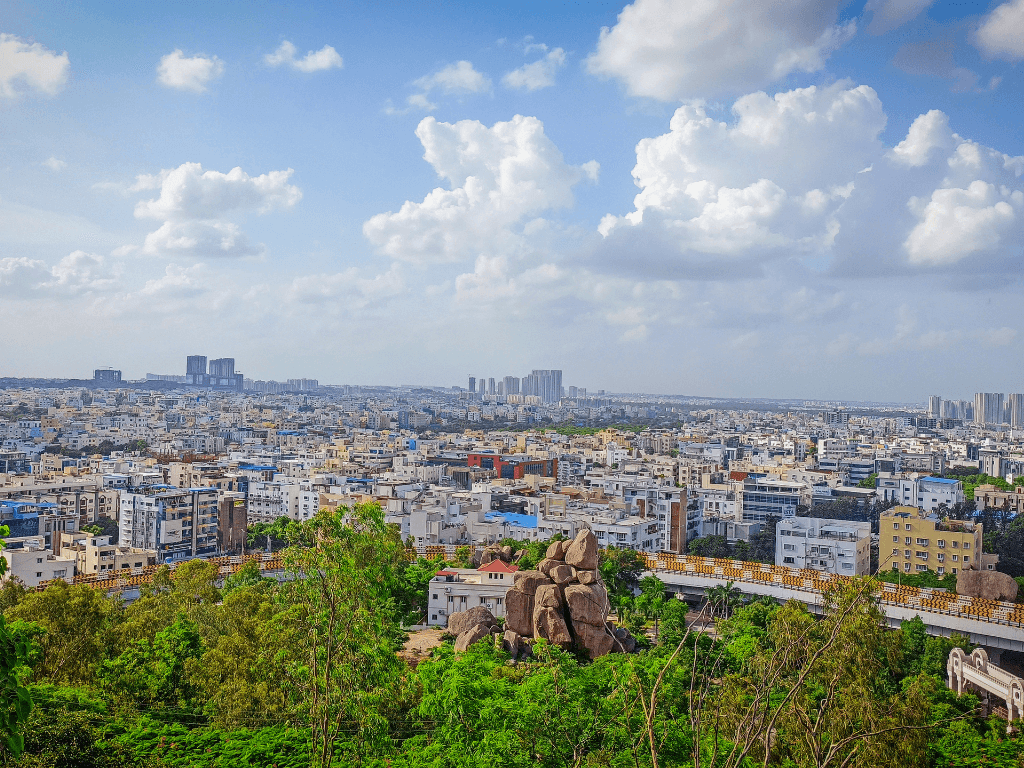

Hyderabad, with a high population density of 18,161 people per square kilometre,[28] is the only city in India to offer unlimited FSI norm which has led to the city’s rapid vertical growth. “Most cities with extremely tall buildings — like Mumbai or even New York — have a strong public transport system. This is important as, otherwise, they can build tremendous pressure on its road network, even choke it, owing to very high density. Unfortunately, in Hyderabad, where these structures are coming up, public transport networks are missing and that’s a serious concern,” said architect Srinivas Murthy.[29] The stresses of high density are showing already including in the once-serene Banjara Hills and Jubilee Hills which now sport congested high-rises and malls.[30] There have been calls to pause and bring in policies to address the haphazard growth.[31]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Chennai, where the rapid urbanisation of peri-urban areas has meant massive changes in land use patterns as farmlands were converted into residential areas, is perhaps a case study on the other side of high density growth. Modelling Urban Sprawl Using Remotely Sensed Data: A Case Study of Chennai City, Tamilnadu, published in 2017, found that urban areas increased by 70 percent in Chennai between 1991 and 2016. “The study demonstrates how the increase in urban built-up areas have eaten up most of the city’s ‘bare land’. Valuable vegetation and agricultural lands have also been lost. Almost all the coastline of the region was covered by urban settlements by 2016 – an alarming rate of conversion of the mangrove forest area. This vegetation provides important ecosystem services, such as protection from Tsunami, cyclones, and other ecological disasters,” writes Stockholm Resilience Centre.[32] In June this year, an Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) study recommended a shift in urban planning to prioritise the needs of the poor and take into account labour patterns, real-time shifts in migration, capital flows but suggested TOD models and Floor Area Ratio (FAR) incentives to ensure affordable housing, and maximise the benefits of metro and bus infrastructure.[33]

Cover Photo: Wikimedia Commons