In June this year, the Kolkata Municipal Corporation undertook a massive drive to remove vendors from the city’s streets and pavements, including Salt Lake, Gariahat, Bolpur, English Bazar. This was ostensibly because the “illegal encroachments” made movement difficult for pedestrians and vehicles.[1] As the issue turned controversial, chief minister Mamata Banerjee halted the action and asked vendors to clear these areas themselves.[2]

During the tension, Banerjee put her finger on the pulse of this vexed issue. “They (officials) allow hawkers and then remove them with bulldozers,” she said, remembering that a survey, needed as per law, was not done. But it has been pending for ten years. This saga not only violated the rights of the poor but the language – “cleaning up dirty people” – too insulted them.[3] With the rule of 2.5 percent of population allowed street vending, the 15-million city of Kolkata can have 3,75,000 vendors. To remove the rest, there has to be a legal process.

This story is repeated in cities across India. A cityscape is nothing without its street vendors, hawkers and other informal workers occupying its visible public places and it is accepted that cities would not function without their presence. Yet, authorities view them as violators, its municipal system tags them all as encroachers, and people see them only as annoying obstructions on footpaths.

This should not have been the situation ten years after the Street Vendors Act was brought into force with great fanfare. What has changed? What changes have they been able to influence in cities that need their services but not them? There are an estimated four crore [4] [5] vendors in India’s cities. The vendors, given the average family size of five, support nearly 20 crore Indians.

How many vendors are unlicensed would be clear only after surveys, as specified in Chapter 2, Section 3 (sub-section 3) of the Act, are done. Regardless of that, evictions and confiscation of their goods continue.[6] [7]

Worse, they are justified by large sections of the media and the public.

The evictions underscore the point that drafting laws does not, by itself, ensure change on the ground though the Street Vendors Act was needed to push for change. For substantive change to happen on this complex issue, unions that show collective bargaining power, sustained campaigns, and responsive administration are needed. Bhubaneswar shows how a city can make hawkers a part of its urban fabric by building vending zones and kiosks for hawkers.[8] though only 329 vendors exist, as per the BMC website. This did not happen without a strong organisation of vendors.

Complex and long-standing issues of hawkers and vendors in city spaces cannot be addressed without coalitions and unions which, since 2000, has been the National Hawkers Federation (NHF). In the initial years, the federation campaigned for a national law to protect hawkers’ rights; that they had a right to spaces in cities needed clear articulation even for the hawkers themselves. After the 2014 law, the focus of the NHF has been to ensure that street vendors are able to assert their rights which includes their right to work in the allotted space.

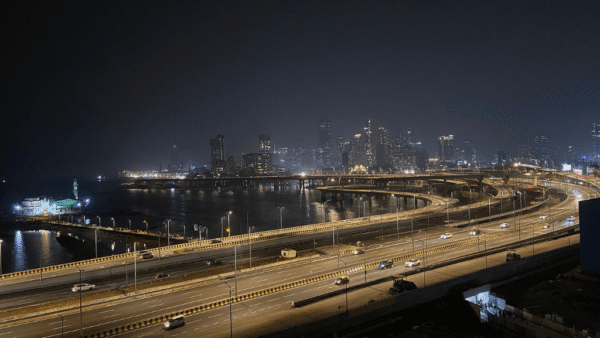

Photo: Nikeita Saraf

Changes through law implementation

The ‘Street Vendors Act, 2014, Protection of Livelihood and Regulation’[9] assures protection of livelihood for hawkers but this has not happened. Evictions are frequent and continue as if the law did not exist. Despite the Act stating that hawkers cannot be evicted at night, there are several instances of municipalities confiscating carts at odd hours, keeping us in the NHF on duty 24×7 to intervene and remind the authorities about this law. Our intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic ensured that the Ministry for Housing and Urban Affairs issued an order against police harassment in May 2021 (see order below).

The fundamental change vendors and the NHF would like to see is widespread awareness of this Act, an end to regular evictions of even the licensed hawkers, and the inclusion of hawkers-vendors in processes of urban planning and governance.

In Vadodara, as in the rest of Gujarat that I am familiar with, only about 40 percent of the vendors have been issued the certificate of vending, or colloquially called licence, but even they are not protected from eviction. The others do not know how to be part of the legitimate process though they serve important needs. Money is involved for the administration. If a vendor is picked up as illegal, he has to unofficially pay around Rs 2,000 to have his cart and goods released. Vadodara Municipal Corporation accepts there are about 11,000 vendors in the city and it charges from Rs 500 to Rs 3,000 as fee.

Whether in Vadodara or other cities, licence and documentation has no value during evictions; municipal authorities spare no one. The licensed ones get their stalls and goods released later while the unlicensed ones have a hard time. Of these, a few manage to get receipts from authorities and are better off than those who have no documentation at all. Without documents, vendors suffer when cases are in court. Only when surveys are done as per the law and Town Vending Committees start functioning can the true picture of licensed-unlicensed be revealed.

Therefore, the implementation of the Street Vendors Act is critical to changing the situation on the ground and its narrative in the public. In fact, we want governments to form monitoring committees to examine the status of the law’s implementation so far and amend the Act to include a penalty for the authorities that enforce it illegally or incorrectly against vendors as a tool of harassment.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Include hawkers in city planning

The community includes urban street vendors, rural street vendors, and railway vendors but the Act, surprisingly, excludes rural and railway vendors. The NHF demands that they be recognised and protected too even if special rules have to be formulated. Our estimates are about 80 lakh vendors on the railway network and railway streets.

There are at least 2 to 2.5 crore vendors across urban India which includes towns. Obviously, they are in large numbers and more visible in metropolitan cities. Cities and towns must dedicate space for vendors in return for a fee which, naturally, recognises them as legitimate. In courts, however, local authorities justify action against even these vendors as the standard operating procedure. This runs contrary to the Act and has to be sorted out.

Equally important is the active participation and involvement, through statutory means, of vendors in the urban planning and governance mechanisms. Development Plans or Master Plans for cities and towns are drawn up as if street vendors do not exist but the need of the hour is that the formal planning process recognises this informality in cities and towns – and provides adequate spaces for them which are earmarked. Kolkata has now begun the process of providing them spaces; Mumbai’s market spaces are inadequate or non-feasible.

Planning still does not take vendors into the process though the Act provides for it. Each city or town is meant to have a Town Vending Committee in which vendors will be 40 percent of the members elected by the community and 10 percent would be NGOs working on the issue. The representation of vendors at the planning stage is important for both the community as well as the city.

To prepare vendors for this, local leaders have been identified and national conferences have been held. We have also taught them how to shoot videos of evictions but it takes a lot for vendors to stand up to the authorities; it’s easier if NHF volunteers are around. My experience is that every time we have a tripartite meeting with vendors and government departments or local authorities, our presence becomes a morale booster for the vendors.

People rely on street vendors for their essentials but also see them as encroachers, dismissing their rights. How many people know about the Street Vendors Act? Their perspective will change when vendors are treated as legitimate constituents of a city, equal claimants of space, and unlicensed vendors are regulated. But who decides which vendors are unlicensed when the Act, specifying this, has not been implemented? The onus is on the authorities to provide space for both vendors and pedestrians rather than set them up against one another. The pedestrian versus street vendors is a manufactured narrative.

India’s cities cannot copy the western model of planning with zero street vendors; the Global South has to approach it differently. The fact is that bazaars and street vending have existed in the oldest of societies across India, contributing to their growth and prosperity. From goods-specific markets to weekly and night markets, they formed a part of a city’s socio-cultural fabric and heritage; they existed when malls did not. For decades, street vendors have offered people, especially the working classes and migrants, access to affordable food. What will be the impact if these vendors are barred?

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Vendors battle climate change

Street vendors are among the most susceptible to the vagaries of climate change Issues of climate change loom large on the very existence of hawkers.[10] As the past few years have shown, people working outdoors such as vendors face extremely high heat, suffer from bitter cold and highly polluted air, and are forced to brave the frequent flooding after heavy rainfall. Rarely does their plight make it to the climate change negotiations and climate mitigation steps taken in cities.

One of the key focus areas of the NHF has been to get the central government and policy makers to recognise that farmers and street vendors are among the first to be hit by climate change-triggered extreme weather events. We got ourselves a seat last year at the international climate summit COP28 in Dubai to draw attention. So, a beginning was made but a lot needs to change in the way cities are built to ensure that vendors are provided during the extreme weather events. Simple measures such as early warning systems and safe shelters can make a big change to how they face these events.

Large corporations also shift their blame to vendors in the climate mitigation actions. Street vendors were made scapegoats and fined for using plastic carry bags as in Guwahati [11] or Delhi.[12] The ban on single use plastic since July 2022 has deeply impacted vendors.[13] [14] Why was a ban not brought on the production of plastic instead and manufacturers clamped down on? We also advocate a move away from plastic bags but it is unacceptable that street vendors are penalised for using them while the rest of the plastic food-chain continues as it is.

The government has proposed the ‘100 Food Streets’ initiative across India[15] These should be plastic-free and have washing centres. The NHF has suggested a model, in partnership with an European organisation,[16] for washing cutlery in a hygienic way, with no-wash areas at food stalls, which can also generate employment.

Cities lack public toilets and the brunt of this is borne by street vendors, especially women. Vendors would also find it convenient to have storage space near their vending areas rather than cart everything from their homes daily. Ranchi has put this in place where a street textile vending zone has separate godowns under every stall. This also means that the vending zone has been a part of the city’s plan. This is possible in other cities too.

The essence of a city lies in its people; the interdependent relationship is a crucial part of this narrative. In no city does it have to be vendors versus pedestrians or vendors versus authorities; this needs to change.

Jay Vyas, besides working as a website consultant, is an activist with the National Hawker Federation which has been instrumental in shaping India’s street vendor legislation. He now leverages its presence in every state of India to advocate for the rights and livelihoods of street vendors. He provides tech support to Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey