“Record breaking temperatures”

“Hottest summer ever”

And such headlines show how the mainstream media reports peak heat wave cycles in India. The emphasis on the here-and-now misses critical nuances of the heat narrative – how the marginal groups are impacted and what can be done about it. High temperatures and heat waves do not impact everyone in the same way or equally, nor does everyone have equal access to measures to cooling.

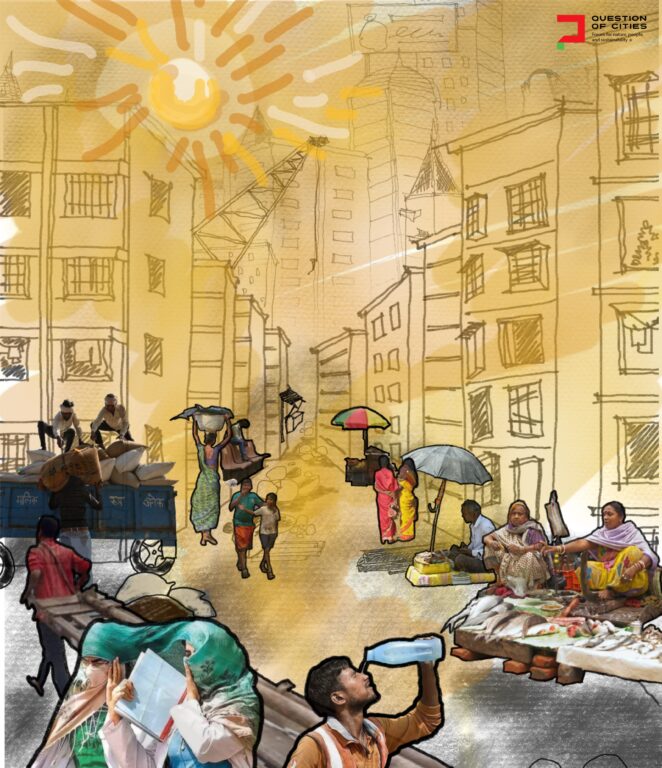

The most impacted groups are, of course, people working in the informal sectors of the economy, farmers, fisher folk, gig workers, and daily wage workers involved in construction and so on. The other blind spot in the mainstream heat narrative is a person’s vulnerability and their position in the social structure which, besides class, includes caste, gender, and disability. Each of these intersections influences the impact of heat waves on individuals and their ability to work or live comfortably in the gruelling months.

Women are among the particularly vulnerable groups. In the socio-cultural context, women are still the primary care-givers in households, they use more public transport than men, they make more chain-trips (many activities combined together) often on foot, women in the informal sector do not have adequate public restrooms and dedicated shelters, and women spend long hours indoors in poorly-ventilated homes near gas stoves or wood fires. Heat waves exacerbate the existing gender inequalities.

The gendered impact of heat is beginning to be acknowledged but we propose a feminist lens to understand and address the issues that arise from heat waves, a lens of care and well-being.

What does a feminist lens mean?

It means centering well-being and care in solutions, going beyond physical health and infrastructure. It involves awareness, resources and practices of care as part of climate adaptation. This is hardly seen now. The work on heat should not repeat the mistakes of climate and health campaigns in India, specifically air quality, where after years of resource and policy changes the gendered burden of air pollution is hardly tackled.[1] While critical work has happened on indoor air quality like access to clean cooking fuels[2], an overall feminist approach is largely missing. Here lies the opportunity to create more grounded, holistic and long term climate campaigns on heat. This is what we aim to work towards with similar groups.

Practices of care include transfer of traditional indigenous knowledge in nutritional health, adapted to a region and season, or the creation of common kitchen gardens amongst Adivasi women in Bhimashankar Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra.[3] Yet another example is that of self-help groups though they are inadequately funded. Such practices of care are irreplaceable, especially when it is about women and female-bodied persons and more so in indigenous, Adivasi and Dalit communities. The public health system should be held accountable for their well-being, especially in the context of cities, but it is not even geared to cope with heat-related ailments.

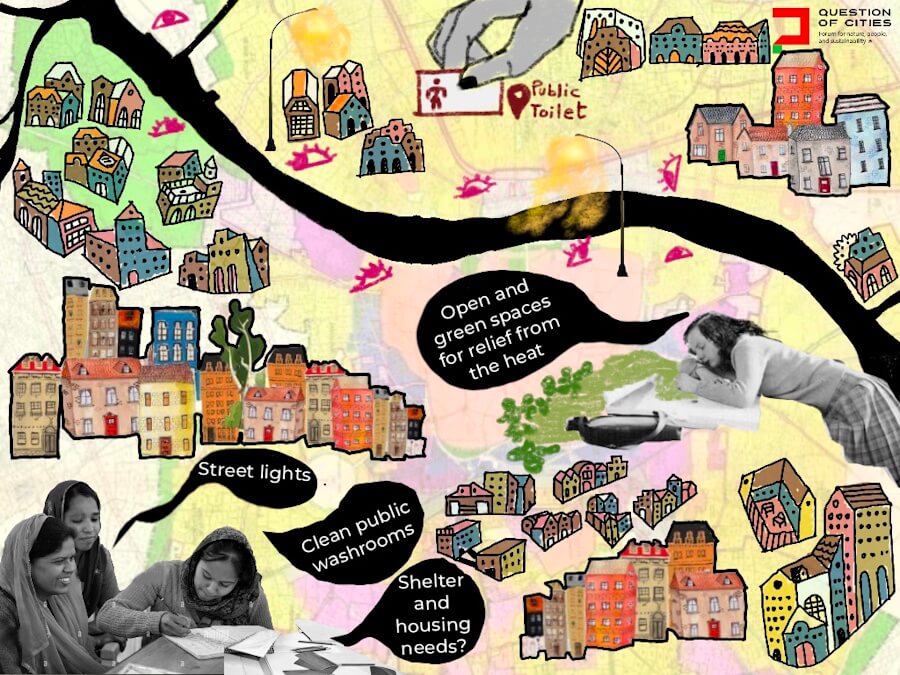

While much has been said about technology and solutions, we need to understand what women want as practical realities. In the summer of 2022, we began to unpack the adverse impacts of heat stress on our emotional, psychological, and physical being — and that’s how the Heatwave Action Coalition (HAC) came together. HAC is a citizen, science-based, feminist collective asking critical questions on extreme heat, seeking solutions together, and influencing public narratives on heat and gender. We ran a small survey. Though limited to about 100 women in urban spaces, it showed what would help them combat heat.

One of the big outcomes was women’s need for state subsidies. Most working-class women spoke about subsidies for electricity bills because households consume more power in the hot months. At the technical level, the need of the hour is affordable cooling systems. Secondly, they want subsidised treatment for ailments directly and indirectly linked to heat – not merely for urgent heat-stroke care in hospitals but overall treatment for heat stress and heat exhaustion.

Thirdly, they expressed the urgent need from public and private healthcare professionals to understand their bodies better and how heat stress complicates their comorbidities. This holds true for female-bodied persons and trans persons too who find it difficult to get the required medical attention. Both state and non-state players in healthcare need to step up. A clear example is training the staff at Primary Health Centres to listen, understand, and provide nuanced care to women and other genders. A bottom-up approach should also be included as a mandate with private companies which employ women and trans persons.

Overall, women want on-the-go clinics, kiosks, care centres in offices or clusters of offices offering heat mitigation measures. Even having heat centres in clinics in commercial complexes and office spaces would be a step forward but the more public these facilities, the better. The underlying approach is – or should be – of care and well-being rather than providing infrastructure only. And this should be driven by a rights-based and justice-oriented framework rather than a women-as-beneficiaries approach.

Why focus on women and other genders

A solid reason for proposing the framework is the impact of extreme heat on women. Pregnant women face a higher risk of gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and hospitalisation.[4] Heat exposure during pregnancy also increases the likelihood of stillbirth, low birth weight, and preterm birth.[5] Additionally, extreme heat has been linked to a higher risk of gender-based violence, further endangering women and girls.[6]

When exposed to heat stress, menstrual women may experience disruptions in their hormonal balance which can lead to heavier bleeding, irregular periods, and increased pain.[7] Women’s and men’s bodies are not similar, of course, which emphasises the need to address heat impacts from a gendered lens.

Even the minimal gender and heat discourse we have misses the health and well-being of trans, non-binary, queer and female-bodied persons. Also missing is their access to existing health policies and schemes which exacerbates their existing disadvantage. For example, can a trans or queer person walk into the neighbourhood clinic and expect to receive treatment for heat-related illnesses with ease? Hence, it becomes non-negotiable to talk and push for more heat-related work led by these communities.

Cooling as indicator of care and well-being

One of the first stories of heat stress we heard was about women farmers and fisherwomen underscoring how critical the right to cooling is. It is no more a luxury; it is part of the fundamental right to life. Therefore, the access to cooling matters. “As the mercury rises, access to cooling no longer remains a privilege, it becomes a fundamental right,” Dr Chandra Sekhar Pemmasani, Minister of State for Rural Development and Communications, acknowledged at a recent event.

Heat is not just a climate issue; it is a human and health crisis. But its translation on the ground needs a large multi-stakeholder and feminist approach. This presents us with a problem but also an opportunity. Will India merely follow the Global North on how it went about cooling, or will it invest in people and ideas that make cooling accessible, equitable, and critical? Cooling has to reach women; it cannot remain a privilege in the climate crisis.

In 2021, fisherwomen at Mumbai’s Sassoon Docks narrated a shorter selling time of fish due to the high spoilage caused by rising temperatures. Sitting in the fish markets was difficult due to the heat and the higher expenses on storing ice for fresh fish hurt small-vendor budgets. Fewer customers came to the markets; the demand was in the evenings instead of daytime, or they could switch selling door-to-door services which meant more labour, costs, and still battling heat.

Another example is of women farmers owning less than two acres of land. In Maharashtra’s Marathwada region, they have had to either switch from primary crops to resilient cash crops with lower risks of post-harvest spoilage like sugarcane and cotton or adopt multi-cropping and farming models they would traditionally not follow. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reported, in 2022[8], an annual loss of 40 percent of fresh fruits and vegetables worth USD 8.3 billion in India, most of it due to heat. The switch from food crops to cash crops directly impacts the nutrition and food security for families, especially women.

Cooling is linked with economics and livelihoods, but has to be recognised as key to the health, wellbeing, and productivity of people too. India is characterised by rising per capita income and rapid urbanisation which leads to a rise in the demand for cooling but has a low penetration of cooling devices if we discount air-conditioners in cities. Access to cooling is uneven with women and other genders.

A quick glance at the Urban Heat Island (UHI) index shows the problems. It is the lop-sided land use, over-concretisation of cities, lack of parks, green covers and water bodies. Yet, conversations and decisions leave out women; women are rarely found at the highest levels of decision-making. Extreme heat is no different. If more women from affected groups have the opportunity to decide on the gender-heat issue in urban planning, inclusive city design, housing and shelter needs, extreme heat would be addressed with a gender-sensitive lens.

The current focus is mostly from the lens of economic loss or productivity loss. This is important for business but it is not enough for society; a holistic and gendered approach is missing from this narrative. The need is to recognise that extreme heat is a slow-burner climate event. Unlike other extreme events, heat waves do not come in a specific time capsule but build over time and unleash in episodes. The body is pushed to its limits and quickly impacts a person’s emotional state. Currently, heat waves are not recognised as a national disaster which creates issues for funding programmes under State Disaster Mitigation Fund and National Disaster Mitigation Fund.

Plans and more plans. But what’s next?

Most of urban governance and public health discourse de-links extreme heat stress and its gendered impact. The one-size-fits-all approach and argument in the public health system and climate action plans is limiting and inadequate for women. Though Heat Action Plans (HAPs) have been getting attention lately, they rarely represent the unequal impact on women and other genders, or respond to their needs.

Through HAC, we noticed how the conversation on heat is technical and focuses on action plans which do not have enough funding.[9] Additionally, they do not have a needs assessment for the most impacted groups. Beena Johnson, general secretary of the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights, was on point when she told the media that “the Heat Action Plans formulated at state, city and district levels do not take the impact on vulnerable caste groups into account,”[10]

At HAC, one of our focus points is to look at solutions to climate events like heat with different lenses from the usual – lenses of gender and marginalisation. HAC joined forces with the Amazon India Workers Association in writing to the Haryana government protesting the inhuman treatment of workers at the company’s Manesar unit where they were not even allowed toilet breaks. HAC has, organically, attracted women and queer people on the issue from the creative arts, policy, law, research, IT and many streams.

Our next steps will focus on public accountability of heat, by gathering data through means of Right to Information and other formal written submissions, collaborating with stakeholder groups of labour, women, and the youth where we can amplify messages and mindfully co-create interventions on heat impacts. We are also building an open resource and knowledge centre online, which includes webinars with experts on heat from Telangana, Tamil Nadu, and potentially Maharashtra.

HAC wants to foreground the gender-heat intersection in conversations, in public discourse (like this essay), in policy evaluations, in action-taken reviews not because it is the only one but because it deserves all the attention possible. We want to propagate the idea of placing people’s well-being at the centre of heat mitigation measures, rather than only providing infrastructure or technical measures, both by state and non-state organisations – the well-being of women and other genders, of society itself.

Sarita Fernandes is a climate policy expert that focuses her work on the intersections of climate change with land use, gender and food.

Ruhie Kumar is an independent climate campaigner focusing on impactful climate narratives which are rooted in empathy, care and action.

HAC is volunteer run, a group of interested, curious and caring minds and hearts who are exhausted by the state of things, but we are also finding the spark together to channelise our anger, rage and sometimes helplessness into something meaningful, where the end goal is justice and care for all.