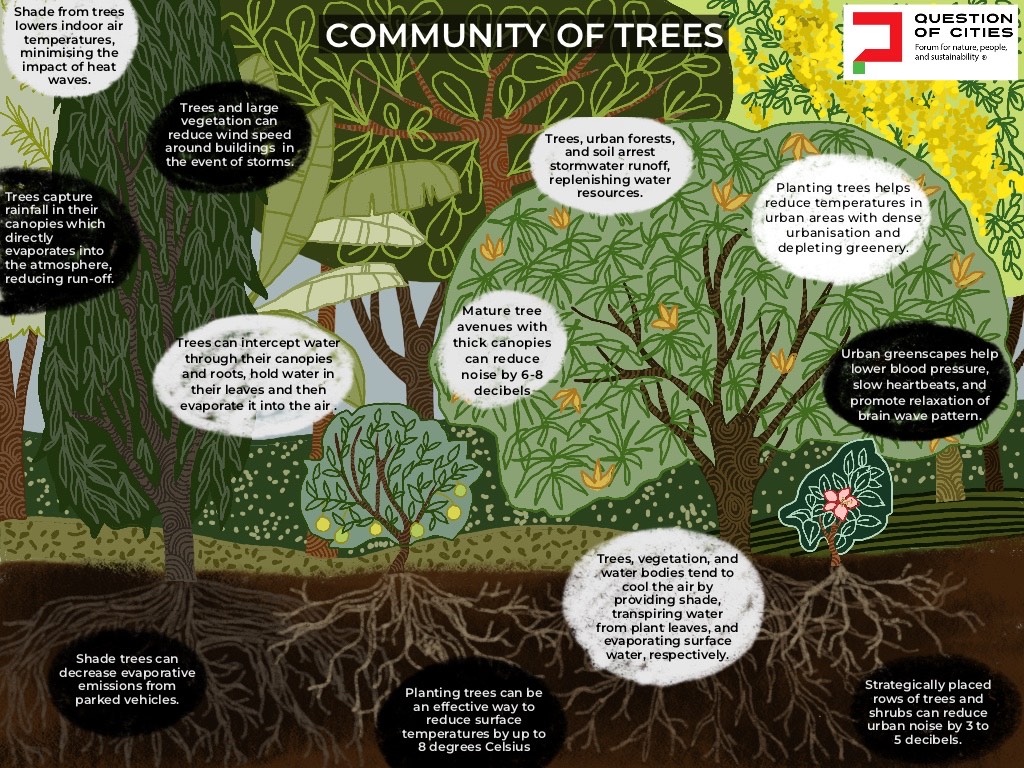

“These are not merely trees, these are entire tree ecosystems, like our families, that will be uprooted. Imagine if your entire clan is destroyed.” These words were said with great passion by an environmentalist to a large group assembled to protest the planned hacking down of more than 2,140 trees in Mumbai’s Aarey forest[1] to accommodate a metro car shed. The environmentalist was not being hyperbolic or emotional. Trees, even in cities, grow and thrive in clusters, in communities or families as it were, creating and sustaining ecosystems that are fascinating to watch besides being useful to people.

Eventually, of course, these marked trees were demolished in the dark cover of the night when activists and environmentalists were not around, the car shed was constructed, and the Metro 3 line has been partially operational for the last three months. The photographs of then-and-now of that stretch of Aarey[2] are stark, the green replaced by the brown and grey, the natural traded for the constructed. This is not to suggest that the metro line should not have been built – that’s another tale – but that the car shed need not have been located in that expanse of green, at a cost paid by communities of trees. Do the roughly 20,000 daily riders on the underground metro spare a thought for these lost communities and families? Does Mumbai care?

Writing at the time, Rashida Atthar, social scientist and naturalist, described it thus: “In the Aarey forest, if we consider the major species found in large number at the car shed site like Bombax Ceiba – Katesavar – 357 in number — the tree interacts with biotic factors like the birds and insects, with other trees around for pollination, and the fungi and other organisms that are associated with its roots. The non-living or the abiotic factors in the environment include sunlight, wind, rain, rocks, soil type, temperature, concentration of oxygen, and other gases to which the tree will be exposed during its lifetime.”[3]

In the moist deciduous forests that Mumbai has, she added, “trees like Katesavar (Red silk cotton tree), Asan Bridelia Retusa, Dhawda, Anogeissus latifolia, and other species shed their leaves with varying duration. Summer sees some plants flowering and fruiting. Monsoon transforms the forest in its very first showers. Herbs and wild flowers of various hues and colours sprout and fade away only to be replaced by more fascinating ones. The forest comes alive and the streams provide rich marine life.”

The worth and value of an individual old Baobab, Coconut, Banyan, Neem, Peepal and tens of other species are known to those who see them as life-sustaining ecosystems. A single tree is history too as the khirni tree is, estimated at nearly 600 years old, from the time of emperor Feroze Shah Tughlak, at the dargahs in Chirag Delhi and Mehrauli.[4] The Delhi government, 2016, recognised 16 ancient trees as the city’s “natural heritage” – individual trees that have seen generations come and go.[5]

Mumbai, it’s hard to believe now, was once termed the “land of trees” in The Rise of Bombay; in The Gazetteer of Bombay City and Islands published in 1909, M.S Edwards describes the “palm-groves and tamarind-trees, “groves and orchards of ack-trees, brabs, ber-trees and plantains, creek of the fig trees, grove of bhendi with some delight, as the Mumbai Tree Project pointed out.[6]

If one tree holds pure joy and enchantment, besides performing a host of functions for other life forms, then a community of trees is a veritable green party; chop one or a few, and the entire cluster is affected.

Photo: Vaishali Saraf

A social network

The idea that trees, in cities just like in dense rural forests, build a community of their own, as a survival mechanism or a natural information channel, is a powerful one. A single tree, regardless of the species, is important but its power to make a difference to the climate around or provide ecosystem services to people and other life forms comes from being in a community. There are more lifeforms and more connections, pathways, in the soil than we can allow ourselves to imagine.

This has been powerfully brought out by forester and author Peter Wohlleben in his book The Hidden Life of Trees – What They Feel, How They Communicate: “If you look at roadside embankments, you might be able to see how trees connect with each other through their root systems…Scientists in the Harz mountains in Germany have discovered that this really is a case of interdependence and most individual trees of the same species growing in the same stand are connected to each other through their root systems. It appears that nutrient exchange and helping neighbours in times of need is the rule.”

Roots create what looks like a social network, he writes and then asks why trees are such social beings sharing food with their own and, sometimes, even with competitors. “The reasons are the same as for human communities – there are advantages to working together. A tree is not a forest. On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. It is at the mercy of wind and weather. But together, many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores a great deal of water, and generates a great deal of humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old. To get to this point, the community must remain intact no matter what…every tree is a member of this community.”

That community of trees is kept nourished by roots extending towards one another, unseen above the soil, creating a network of capillaries much like in the human body. Trees huddle together, if we look closely, often nurturing smaller plants and shrubs in their canopy. “We now have a much greater understanding of forests and the fungal networks that connect trees. Through intricate mycelial webs, fungi and trees redistribute and share nutrients and water, and send almost instant recognition and warning signals to each other,” wrote David Suzuki, the acclaimed Canadian academic, broadcaster, and environmental activist.[7]

A beech forest is more productive when the trees are packed together with a clear increase in biomass, above all wood, is proof of the health of the forest throng, Wohlleben cites from research conducted in Lubeck, north Germany. He adds: “When trees grow together, nutrients and water can be optimally divided among them all so that each tree can grow into the best tree it can be. If you ‘help’ individual trees by getting rid of their supposed competition, the remaining trees are bereft. They send messages out to their neighbours but in vain.”

This is how cities must see urban forests – not a tree planted here and there amidst the grey concrete but as life-sustaining ecosystems complete in themselves that stand quite miraculously amidst the dense construction around them. Mumbai has 18 such urban forests, as identified in a survey conducted by the environmental non-profit Vanashakti.[8] Every city must urgently recognise and protect the remaining urban forests across its expanse – for the forests and for people.

Native neighbours

The community or family approach to trees is key to the realisation that naturally-occurring species in cities, or trees native to the area and soil, should be preferred over trees imported from other ecosystems, climates, and soils. Or even trees that may belong to another part of the world but are planted for ornamental purposes or to tick off boxes under tree planting exercises routinely undertaken by municipal agencies and tree authorities. This study[9] showed that trees “significantly cluster” by species and “introduced species significantly homogenise tree communities across cities while naturally occurring trees (“native” trees) comprise 0.51–87.4% (median = 45.6%) of city tree populations.”

In Mumbai, not only did the green cover decline by a whopping 42.5 percent in only 30 years (1988-2018), according to a study published in 2020, in the peer-reviewed Springer Nature journal,[10] but the species of trees have undergone changes too. “Mumbai has 318 species of trees, nearly 50 percent of which are exotic,” observed well-known botanists Marselin Almeida and Naresh Chaturvedi, in their landmark report for Bombay Natural History Society and MMR-Environment Improvement Society, in 2005.[11]

These include Banyan (Ficus benghalensis), Neem (Azadirachta Indica), Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Mango (Mangifera indica), Coconut (Cocos nucifera), Indian Rosewood (Dalbergia sissoo), Laburnum (Cassia fistula), Jamun (Syzygium cumini), Rain Tree (Samanea saman), Indian Almond (Terminalia catappa), Indian Gooseberry (Emblica ribes), and, of course, the Flame-of-the-Forest (Butea monosperma) that covers parts of Mumbai in bursts of colour between February and April. Gulmohar, often seen as indigenous to Mumbai, is not so but has become a part of the city’s green canopy.

The forest department of Delhi identified 78 native species including Amaltas (Cassia fistula), Ashok (Polyalthia longifolia) and (Polyalthia pendula), Bael Patra (Aegle marmelos), Imli (Tamarindus indica), Indian Coral (Erythrina variegata), Israeli Babool (Acacia tortilis), Karonda (Carissa karonda), Katahal (Artocarpus integrifolia), Maharukh (Ailanthus excelsa), Makkhan Katora (Ficus benghalensis var. Krishnae), Putranjiva (Drypetes roxburghii), Sagwan (Tectona grandis), Sonjna (Moringa oleifera)[12]

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Among Bengaluru’s common trees, about one in every four, is the humble Pongam (Pongamia pinnata) and the next most commonly found is Swietenia Mahagoni or ‘false mahagony’. A total of 233 native species and nearly 2,86,000 trees were enumerated across the city in November 2024.[13] Only the IIT campus in Chennai has recorded 42 native species of trees including Neem (Azaridachta indica), Mango (Mangifera indica), Mast Tree, Madras Ashoka or Debdaru (Polyalthia longifolia), Tree of Sorrow (Nytanthes arbor-tristis), Jamun (Syzigium cumini), Indian Gooseberry (Emblica officinalis), Indian Siris, Vaagai (Albizia lebbeck), Sandalwood (Santalum album), Katira Gum Tree (Sterculia urens), Sita-Asok (Saraka indica, Saraka asoka).[14]

“Native trees, as the name suggests, are the flora indigenous to a specific region or ecosystem. They have evolved over centuries, adapting to the local climate, soil, and wildlife. These are the true guardians of biodiversity, supporting a rich tapestry of life forms. The impact of native trees on local biodiversity is profound. Studies have shown that, on average, planting native trees can increase local biodiversity by up to 30 percent because native trees have developed intricate relationships with local wildlife, providing them with food, shelter, and breeding grounds,” explains the Polish-based One More Tree Foundation.[15]

Colonisation brought many exotic trees such as Gulmohar, Rain trees, Tabebuyas, African tulips into the country and plantation drives in India’s cities have been using such non-native species. The benchmarks for selection seem more administrative than arborist – the mandatory Tree Authority in a municipal corporation may have experts but civic decisions go by how little maintenance is required, how easily trees lend themselves to plantation drives, how fast they grow to make an area green. These may or may not be compatible with local soil and native plant species which, in turn, could lead to degradation of the soil in that area, withering or dying of some species and so on.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Most of the exotic species are planted to beautify the place. Once we introduce them, it will take at least three to four years to get acclimatised. Eventually, they became invasive,” says Dr ES Santhosh Kumar, senior technical officer at Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute, Thiruvananthapuram. “If we choose to plant the native species, then we are also inviting the dependent fauna to the area. This is passive way of biological conservation, biodiversity conservation.” Since the introduction of Prosopis juliflora, more than 50 percent of the Banni grasslands[16] in Kutch district of Gujarat have been transformed into a woody vegetation-dominated landscape.[17]

Urban biodiversity and ecosystems, then, are far more intricate and complex than just planting a handful of good-looking trees. Native plants have a large role to play in sustaining and rejuvenating local biodiversity. Creating such habitats – for trees, plants, shrubs, even weeds, animals, birds, insects, and other life forms – is like an intricate architecture in itself. Like building a family, a community, with interdependent relations and networks.

Do human societies resemble the tree communities or is it the other way round? Perhaps, the two feed off each other. After all, as town planner, sociologist and biologist Sir Patrick Geddes said: ‘By leaves we live”.

Cover illustration: Nikeita Saraf