Asad Laljee, cultural curator and CEO of Avid Learning[1], Mumbai

“This year, I read two books that helped me look at Mumbai in new ways. I keep returning to Mumbai, as a subject, not just because it is home, but because it keeps changing and always asks to be understood afresh. At Avid Learning, we continue to explore the many facets of the city through our flagship series, including Multipolis Mumbai and Uncovering Urban Legacies, and these two books added to the ongoing learning.

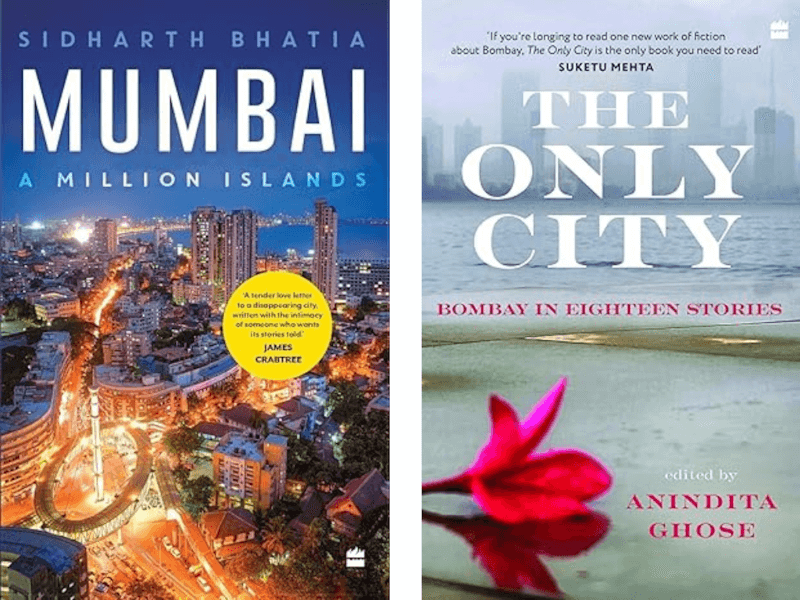

“The Only City: Bombay in Eighteen Stories, edited by Anindita Ghose, shows Mumbai through a set of varied voices. The stories move across the city geographically and socially, from the more familiar neighbourhoods to its hidden corners, with Mumbai standing out as the heart of the book. Sidharth Bhatia’s Mumbai: A Million Islands, on the other hand, offers a very different perspective. It examines how the city is changing physically and socially. It feels like an important reminder of what the city is losing, even as it continues to grow. One uses fiction to show the emotional and human side of the city, while the other looks at the structural changes that shape how we live.

“If I were to write a book on cities, I would put on my arts administrator and cultural catalyst hat and focus on how the arts and culture transform urban life, both culturally and economically. Globally and in India, the creative and cultural sector’s growing contribution to the GDP shows that culture is also an economic engine, a core part of how cities function and grow. My book would explore this connection between culture and the city. It would look at how creative ecosystems shape the identity of a place, support livelihoods, and build stronger communities. It would bring together stories of artists, cultural organisations, neighbourhood cultural hubs, and the everyday creative practices that give a city its character. Mumbai, again, would naturally be an anchor but the book would also draw from other Indian cities too.”

Apoorva Saini, researcher and co-curator of Cities in Fiction[2], a database of literary landscapes, Bengaluru

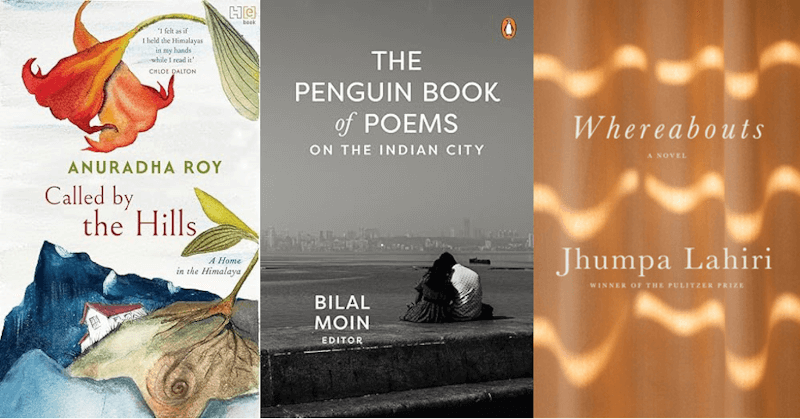

“I just finished reading Called by the Hills, by Anuradha Roy. It’s a memoir/diary about her life in Ranikhet, and how she and her husband built a home for themselves in the majestic Himalayas. The book gives a first-hand account of what it takes to cohabit with the wild nature, pre-internet rhythms of the Kamouni life, mountain dogs and the two devastating Covid lockdowns, our love for the soil and why it makes humans happy. It is a beautiful reflection on the author’s choice to live a slow life (despite its many challenges and oddities) and how it shaped her. The book comes with Roy’s remarkably soft illustrations of the community and landscapes around their abode, which undoubtedly carry the same warmth and care with which she writes about her life in the mountains.

“The second book is The Penguin Book of Poems on the Indian City, a fascinating anthology of 375 poems with 37 Indian cities, 264 poets, and 90 translators working across 20 languages. The scale and scope of the book is cross-temporal, cross-linguistic, and archival in nature – hence the wide spine. The contributors include classical, distinguished, rediscovered, and even first-time published poets.

Last month, for an interview, I spoke with the editor of the book, Bilal Moin. He shared how the Indian city, by virtue of its density and diversity, offers perhaps the closest thing to a national cross-section, his definition of a city poem, poetry that tickles the five senses, why the anthology includes lyrics by rock bands, ‘un-becoming’ as a necessary poetic sensibility of contemporary Indian poets, and the rediscovery of some forgotten poems.

“I have a third title – Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahri. Set in an unnamed European city (perhaps Rome), this is a ‘woman in the city’ novel. The protagonist is an academic, flaneur, and the perfect recluse. She takes us to the streets, markets, bookstores, houses, and institutes that make up her world. She makes us meet her friends. She opens up to the readers about things she struggles to express, or chooses to keep to herself otherwise. She shows us who she is, what makes her disquiet, and that she will be fine regardless of the ways of the world. As a reader, you are compelled into her world, one chapter at a time. It’s a hauntingly mournful yet comforting book.

“As for the second question, I would perhaps write about the microcosms of houses, bastis, mohallas, or high-rise buildings. This reminds me of Madhumalti, a serialised-fiction set in my hometown, Alwar in Rajasthan. I wrote it in Hindi around 2018-19, and the story was about the everyday angst and conflicts of the members of a joint-family living in the old parts of the city. The ‘Cities in Fiction’ project too came to me from a similar fascination of how people and their stories are formed by places and vise-versa. You can read it here.”

Nakul Heble, WIPRO Foundation Urban Ecology Team, Bengaluru[3]

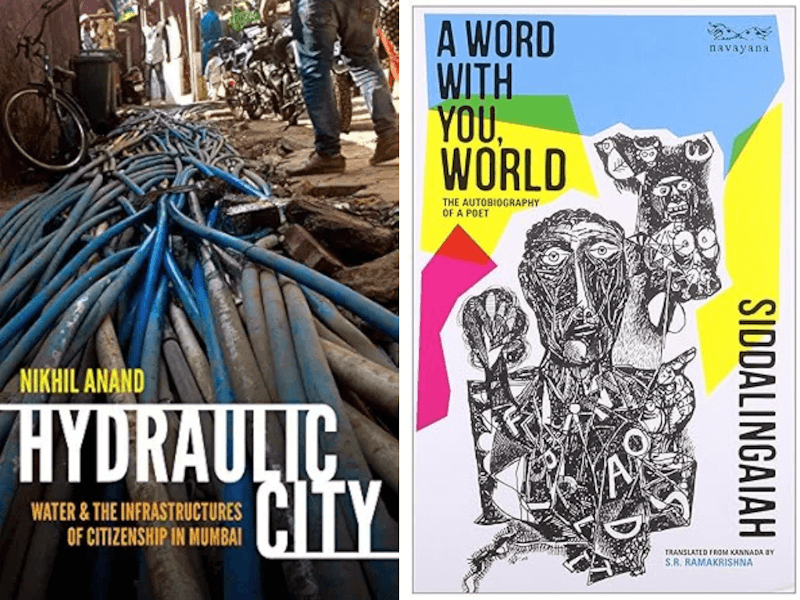

“Two books come to mind that are mostly rereads — Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai by Nikhil Anand, and A Word With you, World, by Siddalingaiah.

“Each year, I go back to reading parts of Hydraulic City, with a fresh set of eyes. The book is a story of Mumbai, its people and their relationship with water, seen through an anthropological lens. It balances academic rigour with simple and relatable narratives and lays bare the everyday struggles of water access. Anand’s work is as relevant today as it was in 2017 when he wrote it, perhaps more people living in the urban margins from tier II and III cities are still waiting their turn to become ‘hydraulic citizens’.

“While I did not live in Siddalingaiah’s Bangalore of the 70s and 80s, his autobiography (translated from Kannada to English) showed me the Bangalore not many have written about. Describing Tamil and Telugu settler colonies of Okalipuram, Srirampuram and other localities surrounding factories and mills of the city, Siddalingaiah took me on a journey through streets that I have myself lived in but never really knew the history of. Dalit hostels and their benefactors, old restaurants (some still standing), educational institutions and Dalit politics are all woven over a city’s fabric that has now begun to fray as it gets rebuilt over and over again.

“If I were to write a book on cities, I would put together a set of stories of how Bengaluru became the pub capital of India. I would hunt down the first few brave entrepreneurs who set up pubs in the central business district back in the 80s to the fast-paced 90s and early 2000s, and tell a story of how they collectively shaped this past of the city’s culture.”

Nidhi Batra, Founder and Director of Sehreeti Foundation, New Delhi[4]

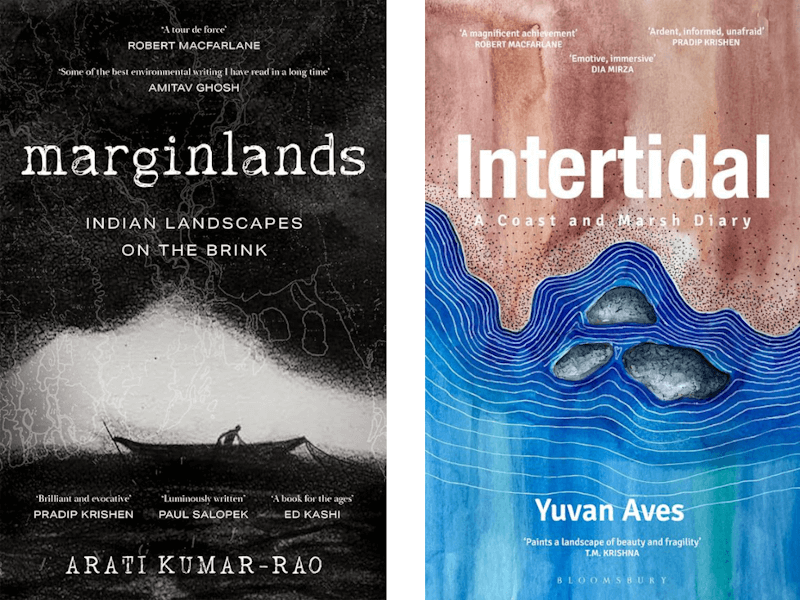

“Arati Kumar-Rao’s Marginlands: Indian Landscapes on the Brink is a powerful and deeply observational book that takes the reader across India’s marginal landscapes — places ignored, misunderstood, or written off by mainstream development narratives. The book weaves storytelling, environmental history, and field observations to reveal how these landscapes and their people sustain and express deep ecological knowledge.

What struck me most is how the book brings alive the knowledge of the commons, the ways in which communities have historically understood, managed, and lived with water, soil, forests, and seasonal cycles. Kumar-Rao’s writing makes visible the patterns we so frequently overlook, highlighting the fragility of these ecologies and the wisdom at risk of being lost as modern planning and policy ignore context-specific knowledge. For an urban practitioner, Marginlands reminds that urban development cannot be disentangled from ecological and cultural landscapes beyond the city’s formal borders.

“Yuvan Aves’s Intertidal: A Coast and Marsh Diary is quite different in form but equally profound. Rooted in two years of careful observation of the coastal and marsh landscapes where land meets sea, this book reads like a diary of slow attention to tides, birds, frogs, worms, and the shifting interplay of human and non-human life. What makes Intertidal resonant for me is its personal and reflective journey. Instead of big theories or sweeping arguments, Aves invites us to slow down, to listen and sense the rhythms of the natural world. Through his immersive observations, he dissolves the binaries between self and world, human and more-than-human, reminding us that cities are not separate from the larger ecologies they inhabit. The intertidal zone becomes a metaphor as well as a physical space. It’s a book about connectedness and kinship, not just with landscapes, but with the processes that sustain them.

“Both Marginlands and Intertidal have shaped how I think about my work in urban contexts by:

- Highlighting interconnectedness and kinship — not just between people and built environments, but with land, water, and the more-than-human world.

- Bringing attention to margins — whether geographical margins, knowledge margins, or perceptual margins that planning processes too often ignore.

- Valuing slow knowledge — the kind that comes from long-term observation, practice, and lived experience, rather than quick metrics or top-down interventions.

Taken together, these books have deepened my sense that urban practice needs to engage with ecological sensibilities and listening practices — not as add-ons, but as core to how we plan, design, and care for places and people.”

Sabah Khan, rights activist and founder of Parcham Collective, Mumbra[5]

“It occurred to me now that I haven’t ever thought of picking books on cities. But I think one book I would love to recommend is something I got as a gift. It’s a lovely book written by Deepa Balsavar titled Nani‘s Walk to the Park. It’s a beautifully illustrated book for children, encouraging them to become more aware of their surroundings and also enjoy the city.

“The book is about a child exploring their neighbourhood with their nani (grandmother). It takes you around a lane of treasures (marketplace), a lane of happiness (where friends live), a lane of mischief (where children play), and many other such lanes. It’s a recognition of all that makes a city vibrant and alive. Something that planners and those who make the city should remember.”

Ranjona Banerji, veteran journalist, Dehradun

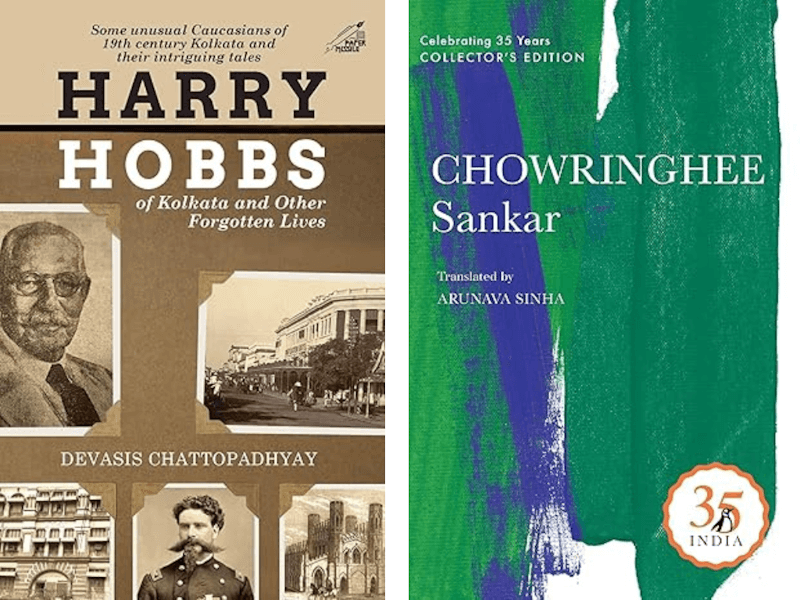

“The most intriguing book I read on cities this year is about a city I went to college in – not in the bricks and mortar sort of way but the ethos, ideas and contributions which make an urban conglomeration. The correct title of Harry Hobbs of Kolkata and Other Forgotten Lives by Devasis Chattopadhyay would be ‘Harry Hobbs of Calcutta.’ Politics and national and ethnic identities, reclaiming of ideas and spaces, have changed the names of our cities but, undoubtedly, the imperial presence in Calcutta, as the capital of India, and then the Bengal Presidency, and now West Bengal, is never far away from the city’s surface. Chattopadhyay does not discuss the usual suspects – Hastings, Macaulay, Curzon, Canning – instead, you have the vital everyday people.

“A city is its past as much as its roads. The second book is a collection of stories about Calcutta that introduces us to the lost people, but whose contributions still reverberate. For instance, Hobbs told his stories to the famous Bengali novelist, Mani Sankar Mukherjee, who put some into his book Chaurangi, which was made into a popular Uttam Kumar starrer, Chowringhee.

“If I were to write a book about cities, where would I go? I have considered this many times, especially about Bombay or Mumbai, because I grew up and worked there but I did not choose to grow old there. Today, in Dehradun, I fight against rampant urbanisation in an attempt to save as much of our natural environment as possible. Humans will congregate, we embrace creativity and chaos. Those of us lucky enough to travel, admire the planned cities of Europe, but Indian cities are often organic, higgledy-piggledy, with vestiges of planning ideas littering the madness. You just need to look at Delhi’s Connaught Place to see how the most efficient and artistic plan can disintegrate into crazy vibrancy. So all these would be in my book: The hopes of people, the lay of the land, the dreams of what could be, and the nightmare of what is.”

Divya Ravindranath, researcher, assistant professor at Indian Institute of Human Settlements, and co-curator of Cities in Fiction, Bengaluru

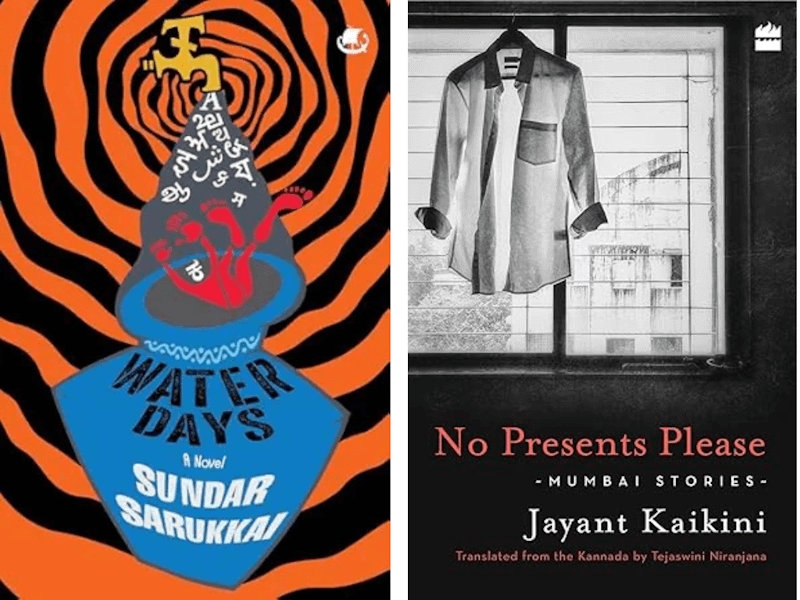

“Sundar Sarukkai’s novel Water Days was immensely enjoyable. The book is set in the 1990s, in a bustling neighbourhood called Mathikere Extension, where the death of a young woman sets off cascading speculations. The neighbourhood (like the cover of the book) has an eclectic cast of characters that speak a mix of Kannada, Malayalam, Telugu, Tamil, and Hindi. Sarukkai does a wonderful job of blending these languages seamlessly — you register and hear the differences in tonality. It is a wonderful reminder that Bangalore’s cosmopolitanism precedes and exceeds contemporary imageries of a global city. Sarukkai is an exceptionally versatile writer, an academic and a philosopher. I have read his scholarly work which is dense and deeply illuminating. I love that his novel carries a certain lightness and humour that gently dramatises the textures of everyday life.

“Another book I have read more than once is Jayant Kaikini’s No Presents Please (translated by Tejaswini Niranjana). I returned to it earlier this year while preparing for ‘Cities in Fiction’ workshop with university students. The book imagines Bombay/Mumbai in ways that English-language writing on the city rarely does. Kaikini’s city is not about over-represented landmarks or popular imagination of the city. It unfolds in the deeper edges of the suburbs. His stories are bewildering, yet if you know the city, you know the absurdness of characters, the speed of life, the unexpected events, the scale is all real. The rhythm is so unique that when I read his writing, I picture my Telugu-speaking parents narrating episodes from their own arrival in the city 40 years ago.”

Srestha Chatterjee, Gender Walks expert, Founding Director of Urban Re-Visioning, Kolkata

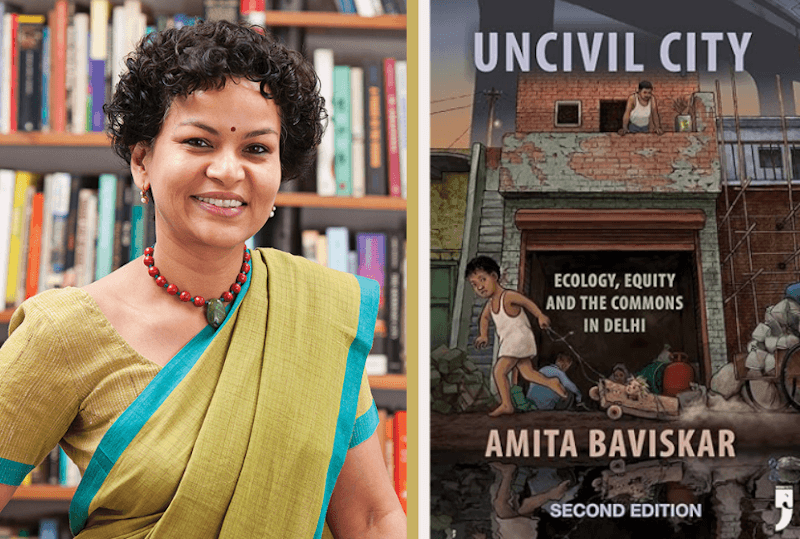

“I read the book Uncivil City by Amita Baviskar and I was impressed because of this one concept that I learned from it named ‘bourgeois environmentalism’, the classist perspective that is supposed to cleanse the essence of a city by removing the undeserving sections of the society who make cities or spaces more uncivil. It was a fresh take on the right to ecologically-balanced urban development and enhanced my own view on building inclusive practices around city-making and reimagining development.

“If I could write a book on cities, it would represent the work that I intend to practise through Gender Community Walks, to really learn about the social dimension of enjoying spaces, how people interact and observe, what are the daily rhythms of life around cities, and how perceptions around city making needs to change through alteration of practices within the private sphere. A city has to change from its skeleton and to do that we really need to alter the way our minds are built. We might be able to build a better picture of the city if we know how to blend imagination, needs, habits and care within the framework of development and urban rejuvenation.”

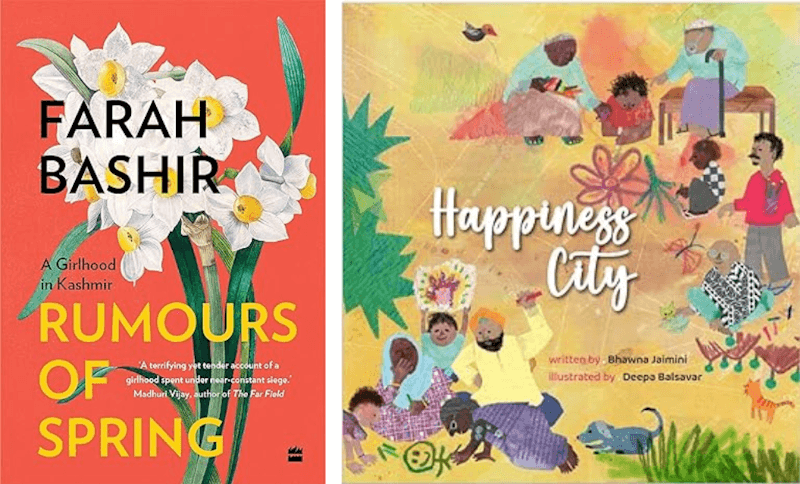

Bhawna Jaimini, architect and founder of Centre for Urban Commons, Bhuj

“I associate cities with happenstance. Everywhere we look, there exists a possibility, a randomness that permeates or rather lurks at every turn and corner. It is this attribute of cities that I have always taken for granted. This year, I read Farah Bashir’s Rumours of Spring, a memoir of the author’s adolescent years in the 1990s in war-torn Srinagar, where every marker of normalcy was upended. The everyday rhythms that we can predict – children going to school in uniforms, newspaper vendors at railway stations, the smell of rotting fruits, vegetables and flowers — all hinge upon a precarious set of civil liberties and systems that can fall apart any moment. One day, you come back from school and realise that you can no longer open your windows. In one of the chapters, Bashir recalls a night of debilitating menstrual cramps but she couldn’t leave her room to ask for help because the wooden house would creak and any unwelcome sounds would invite bullets piercing whatever was left of their lives under siege. No city is too far from Srinagar.

“I have written a book called Happiness City, which is a children’s book about how a city doesn’t need expertise but kindness and care to flourish. My next book will be about a child and a cat navigating through the concrete-scape of a city. I want to show how brazenly insensitive, cruel, and indifferent planning decisions impact the everyday of the most vulnerable. The book is not going to change anything but it might help me protect my own humanity and hope from getting buried under M20-grade concrete they can’t stop pouring over us.”

Hussain Indorewala, academic researcher and activist

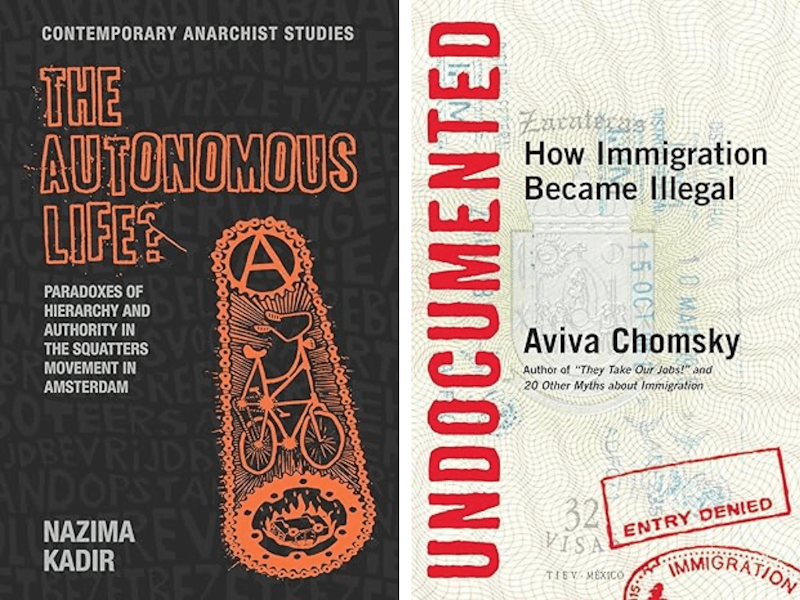

“I don’t find it very helpful to classify books as ‘city’ books and I rarely read books from cover to cover. But there are books I’ve consulted this past year to gain insights about urban affairs. Nazima Kadir’s book The Autonomous Life? Paradoxes of Hierarchy and Authority in the Squatters Movement in Amsterdam (2016) is excellent for activists and scholars, both for its subject matter as well as for demonstrating what good ethnography is about. The author spent three years living as a squatter herself, by which time she could identify the gulf between how people talk about their lives and how they actually live it. It is an unromantic, analytical view of a political movement with which she sympathised but was still able to describe with critical detachment.

“Another interesting book is immigrant rights activist Aviva Chomsky’s Undocumented: How Immigration Became Illegal which provides a historical account of the political construction of illegality and citizenship. In the American context, she explains how the lack of citizenship is a tool of maintaining a dual labour market to make workers more exploitable. Robert Fitch’s The Assassination of New York is an excellent resource for those interested in understanding the role of finance, insurance and real estate in shaping cities. Although written in 1993, the book provides context to understand why cost of living and affordability became the decisive factor in the recent elections in New York.

“Since I live in Mumbai, and write frequently on urban policy and planning issues, I would consider writing more extensively on the real-estate driven transformation of the city.”

Cover photo: Fauwaz Khan