In your long career fighting cases of human rights, you have consistently taken up cases on environment issues. How do you reflect on the link between human rights and environmental issues?

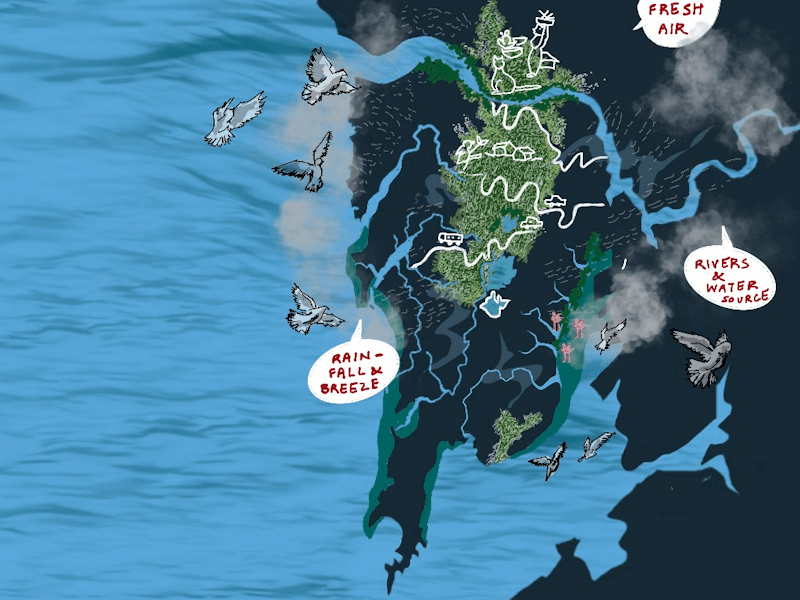

Human rights, for me, always meant a combination of various issues. Ecology or environment was a key aspect because it affected livelihoods and lives of people, whether fisherfolk or Adivasis or city workers. If there’s destruction of the environment, it’s bound to affect everyone. Let’s take pollution. Several cases on pollution against thermal power plants have been filed. One is of the thermal power plant at Bhusaval. This plant operated in violation of all norms and standards of SO2 emissions which affected farmers in the surrounding area, their cultivation reduced, their health suffered. Despite several complaints to various authorities, nothing was done. Farmers and their families continued to suffer while the plant expanded its capacity flouting all possible laws. Several panchnamas have been carried out by government officials examining the damage to the farmers’ lands and quantifying the compensation. Yet, nothing has been done. The farmers have now decided to approach the National Green Tribunal (NGT).

To prevent SO2 emissions, certain devices have to be installed but the Union Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MOEFCC) issued a notification this year which basically exempted power plants from using them.[1] Its circular divided thermal plants into A, B and C categories and roughly 78 percent of cities fall in category C. Clearly, the categorisation was done to exclude a large number of plants. The deadline passed for all categories, there’s no way except to take it to the courts. Every environmental case has had to do with people’s lives and livelihoods.

Housing and pollution are in the courts too. In the rehabilitation of slum dwellers in Mahul, a refinery-dense area of Mumbai, the Bombay High Court had to direct that people there should be relocated and no new families shifted, based on studies of IIT-Bombay as well as the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board. What if this was not litigated?

Yes, of course, this went through various litigations. A large number of refineries, both public and private, are in and around Mahul. They emit highly toxic gases including Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) which are carcinogenic. According to zoning laws, residential complexes should be separated from industrial areas. A company sought permission to construct residential buildings; it wasn’t granted. This was challenged and the court rejected the petition on environmental issues. Several years later, ignoring the Supreme Court order, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation and Maharashtra government provided Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) which enabled builders to bring poor people, basically Project Affected People or slum dwellers, here.

Residents filed an application with the NGT which confirmed the high pollution levels due to which they were suffering from various ailments. It relied upon reports from KEM Hospital, IIT-Bombay, and other public institutions. It also found there were no parameters even to determine the maximum level of release of VOCs and asked MPCB to set them; nothing has been done. So, when the BMC and state government issued notices to people evicted from Tansa pipeline to go to Mahul, the slum dwellers approached the Bombay HC.

It framed the issue: Can you evict people and forcibly make them live in an area that’s detrimental to their health? It decided ‘No’. Several case laws were relied upon, including international, to show that the right to housing is not simply a roof over the head but there must be a healthy and safe environment, assured water supply and electricity, open spaces too. This is not only about individual cases in Mumbai. These can be cited in other cities too.

Environmental cases are complex multidimensional ones that touch upon human rights, social equity, and more.

Of course. Let’s take extreme heat. It affects everyone but it’s rarely seen in terms of impact on workers, both indoor and outdoor, for whom it’s about livelihood. Indoor workers are not necessarily safe because there are no parameters for maximum heat in warehouses and factories. In the huge warehouses of e-commerce companies, temperatures can be well over 36 degrees Celsius. Also, there are no humidity specifications; high humidity can make it hotter and lead to heat-related illnesses.

The impact also depends on age, gender, physique, pregnancy in women and so on. But there are no norms in industrial law. Some unions are planning to file a case for setting standards, regular monitoring, provision for health care, and to identify and treat heat-related illnesses. Even in air-conditioned spaces, heavy and physically strenuous workload means high heat stress. Then, there’s outdoor work which is also debilitating but we still don’t have the Heat Index measurement in India and municipal directives asking ‘people to stay indoors’ are of no use to outdoor workers.

There were pilot projects, including by the Government of India, to evolve a Heat Index for the country but it has not led to norms or rules that would make a difference to people.

The Heat Index is crucial because when the temperature shows 35 degrees Celsius, the Heat Index is closer to 39-40 degrees Celsius which is hazardous. In fact, Oxford University recently did a study showing that even 34-36 degrees Celsius is not safe; they recommended 24-26 degrees Celsius and included density of surroundings and other factors. Our meteorological department, I said in this article,[2] takes readings in isolated areas or vacant land. So, on hot days, imagine how intolerable it is in congested areas where the poor are. They suffer the most.

Governments are charting Heat Action Plans but it’s such a fuss. What is the action taken? How do they ensure that the people who suffer the most have protection? In Gujarat and Tamil Nadu, workers groups have demanded that construction workers be given rest periods during afternoons and not be deprived of wages if they cannot work due to heat. These are important but short-term demands. The long-term issues are critical – how is heat measured, what safeguards are mandated to be provided by governments, what are the obligations on employers or companies. Here, the environmental issue touches labour laws too; heat-related illnesses must be categorised as occupational diseases and notified under the Factories Act.

People have to go to the judiciary for relief or, as we see around the country, to get the authorities to do the bare minimum such as not cut trees. But the courts have not been consistent in favour of ecology – they have, for example, directed the protection of mangroves and wetlands but permitted chopping down thousands of trees. How do you see this?

I have a negative sense of the judiciary as conflicting judgments are being given. There are rights and there are laws – environmental laws, pollution laws, forest laws – but I see two problems. One, how the judiciary interprets these laws. When it’s businesses, developers, and those in power, the interpretation favours them. Two, government policy; authorities come to courts and cite government policy which the court says it cannot interfere with. If the policy is against public interest and the environment, it’s important that courts go into that.

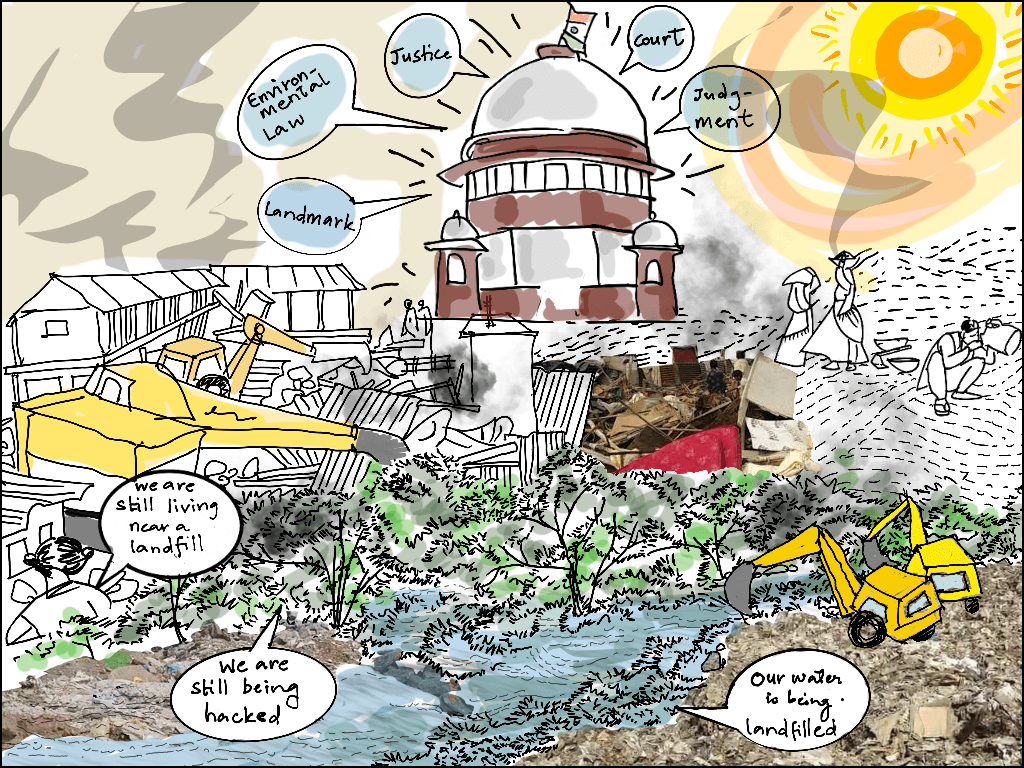

This has happened in the case of the dumping yard in Kanjurmarg which is on a wetland[3] and was polluting the water, the creek, the mangroves, the groundwater and, obviously, the people around. This is on record. The residents and environmentalists have been fighting this case since 2012. This is forest land which means it cannot be used for non-forest purposes – a straightforward case – but it has dragged on. Finally, after 15 years, when it was heard, the High Court held that the Forest Conservation Act had been violated and ruled against a dumping yard there.

The contractor filed an appeal and the order was stayed. The result was that the company continues to dump both hazardous and non-hazardous waste in an ecologically sensitive area adversely affecting the health of thousands of residents. Similarly, in the case of salt pan lands which are affected by inter-tidal waters, the government has allowed residential buildings. With climate change, the lands ought to have been protected. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court threw out the case. The field is now open for builders. These and many such cases have been thrown out where activists painstakingly gathered information about violations.

The other aspect is judicial delays. While the cases drag on, the land and forests are destroyed. Should the courts not see the urgency? Importance is given to tenders and contracts because someone says ‘my crores of rupees are going down the drain’ but forests cut down is not equally urgent. And then, it’s also about which judge hears environmental cases.

Would you say that the courts have been inconsistent on environmental issues? The former Chief Justice DY Chandrachud spoke of the environment as a right but without its interpretation as clean air, clean water and so on, it is abstract. How do you get the courts to interpret this right?

The point is that each judge looks at it differently. That’s why there are such conflicting orders. There are some judges who pass sweeping orders in favour of the environment; they couldn’t care about the consequences. There was Justice Abhay Oka, who came out strongly against post-facto environmental clearances for projects, but an influential party filed a review application which was reopened.

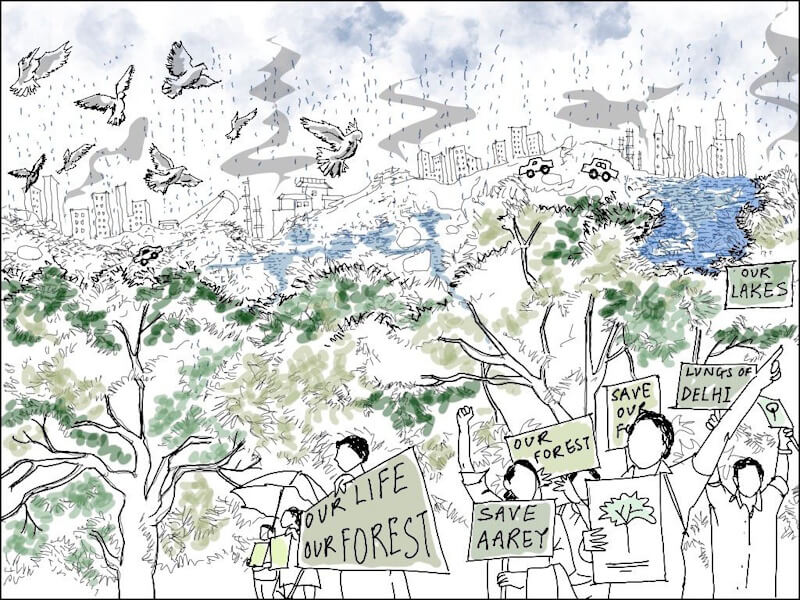

People, even activists, hesitate to go to the courts. You might get an order in favour of the environment but it can be stayed in the higher court and then have an adverse impact on the entire campaign. The legal fight is linked to the agitation on the ground; it cannot be any other way. If people come out, they can get arrested as in the Aarey tree-cutting case in which the state government filed FIRs. This demoralises people as much as the long delays in the court. So, it’s important to align the court cases with the on-ground campaign.

So, is it that the legal battle feeds off, and feeds into, the action on the ground and just taking the legal route may not help the cause?

Yes, I would say that. A good recent example is of the Vadhavan Port[4] project planned in an ecologically sensitive area. The fisherfolk and environmentalists went through the process and finally reached the Bombay High Court which dismissed it. We were back in the Supreme Court which stayed the construction. However, the petition has not yet been listed and petitioners are running around to get the matter heard on an urgent basis while construction might resume any day. The government is going full throttle advertising it, Chief Minister (Devendra) Fadnavis said: “Abhi yeh ho jayega, third Mumbai aayega”. Some locals felt nothing was going to come from fighting, they should accept the compensation offered. Another port is coming up nearby at Murbe. People are very angry with so many ports planned in the region, destroying their land and fishing. At the public hearing on the Environmental Impact Assessment, almost 9,000 people attended and submitted objections, but public hearings are a formality where objections are merely recorded, to be later discarded.

Climate change-related events like intense rainfall and extreme heat, as you point out, are force multipliers of the existing inequalities in society. How do you approach such issues in judicial battles?

One way is by asking for immediate relief in say pollution-related issues, another way is to get the courts to look at the bigger picture. An issue that has been taken up by is the capacity of a city to withstand the building load as the authorities unilaterally increase the buildable area, or Floor Space Index, without regard for carrying capacity. This is the capacity of a city with regard to existing infrastructure like water supply, solid waste management, traffic, flooding, and so on. Some residents of Pune are filing a petition challenging part of the Development Control Rules on this point. The 74th Amendment of the Constitution devolves power to local bodies but, for entire Maharashtra excluding certain towns and cities, a two-member committee appointed by the state government has usurped this power. Also, Development Plans for cities must be specific because each city has its own peculiarities, there can’t be one framework for all.

Somehow, the old binary of development-versus-environment persists among governments and the industry. All that people say is they want this forest or this river as the web of life; they are not anti-development. How critical will the role of the courts become as this battle becomes fierce?

It will be critical, definitely. In the Nagar judgment, the court did a balancing act about open spaces and slum development.[5] The battle between environment and development is a continuing one with the balance tilted in favour of what is perceived as “development”. There are conflicting judgments on what is understood as development. Then, there’s another aspect where people have to go to the courts because the authorities themselves brazenly violate law.

In Mumbai’s Khar Danda, for example, the fisherfolk had their traditional fish drying plots which were shown in the Development Plan too, but the Slum Rehabilitation Authority passed an order declaring a part of it as slum land and giving a bonanza to a builder. A petition was filed challenging the proposal to alter the fish drying area to housing. The Urban Development Department, after much delay, filed a notification which had rejected this substantial modification in 2022, but no steps were taken to protect the plot till 2025. The builder has, by force and with the help of the police, encroached on the fish drying plot. In yet another case, a Pune-based planner filed a petition for floodplain demarcation. Though the state Water Resources Department filed an affidavit that the demarcation was wrongly done, the Pune Municipal Corporation has been opposing everything the petitioner recommends. The court constituted a committee and sought a report within a specified time. The report has not yet been submitted but, without proper demarcation, construction is happening at breakneck speed.

Do you see the judiciary being influenced by the ecological crisis at all?

They are influenced. Pictures go a long way, of say the floods and landslides in Uttarakhand, but it’s equally important that people speak up. Ultimately, it’s a campaign in the courts. It also depends on the judges. In so many cases, orders are not implemented, and the affected parties have to file contempt of court cases. So, every ecological battle becomes an ongoing one in the courts.

The judiciary does need to be sensitised, educated, because the government is blatantly violating the law. Many of the environment laws are either being amended in a regressive manner or withdrawn. For example, the Forest Conservation Act[6] is being amended to dilute the meaning of “forests” and, thereby, undoing the definition of forests in the Godavarman case. The Bombay HC has extended this to include forests which grow subsequently. In Jaipur too, the Dol ka Badh is not notified but is a forest. The government strategy has been to issue circulars which nullify the stringent aspects of environmental laws and expedite permission in ‘national interest’ or ‘ease of doing business.’ So, people are forced to go to courts.

Is this a losing battle?

No, I would not say that.

Are there wins?

Yes, if people come together for protection of their rights by being vigilant and ensuring that public authorities perform their duties.