Tell us about your work. How did it address the impact of density on health in the slum rehabilitation areas you studied?

This is a complicated question. The question of density cannot be looked at in isolation. When it comes to health, density has to be seen in tandem with built form design, light and ventilation, per capita infrastructure and open space, and issues such as long-run maintenance of the buildings. I will explain this in the context of our TB study, Association between architectural parameters and burden of tuberculosis in three resettlement colonies of M-East Ward, Mumbai, India, published in 2020.[2]

Let me give the background. Dr. Ravikant Singh, founder of Doctors for You Foundation, and his team were working in Mumbai’s M-East (civic) ward area, administering the DOTS programme for TB. They realised that some housing colonies had a higher burden of TB compared to others. It piqued their interest. They prepared a proposal, got funded by the Mumbai Metropolitan Region – Environment Improvement Society (a wing of the MMRDA), and brought together a study team which comprised doctors, architects from IIT-Bombay, and I as the planner.

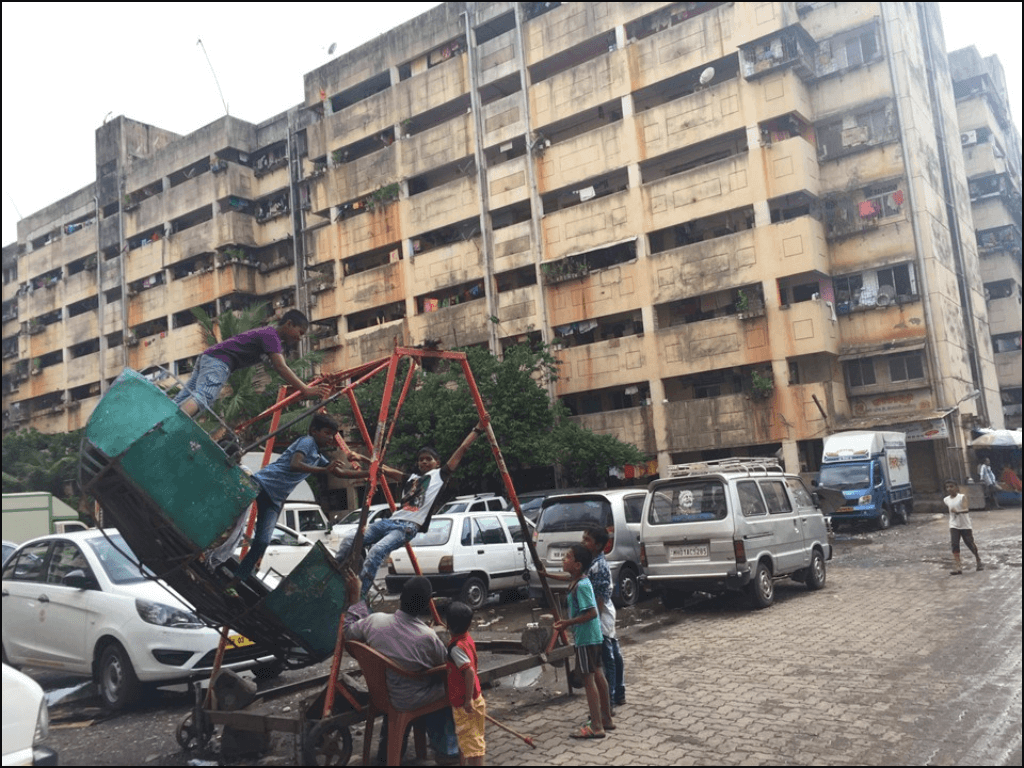

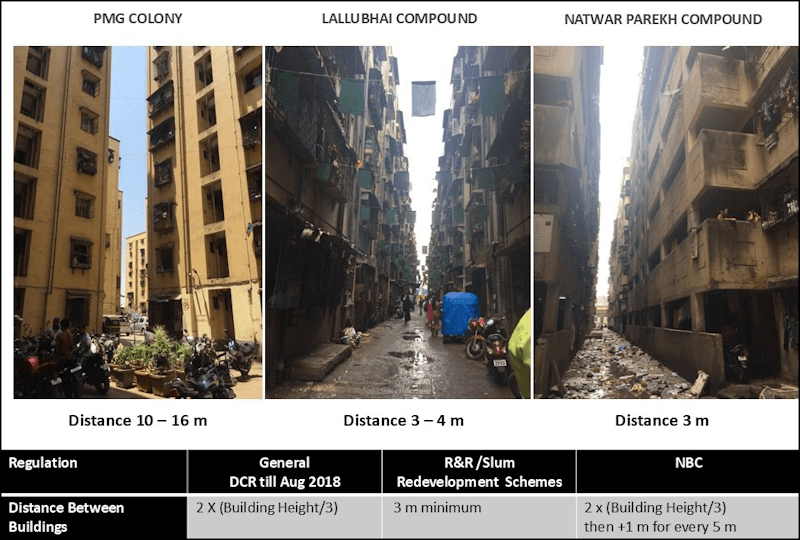

We documented that Natwar Parekh Compound and Lallubhai Compound housing colonies had a higher burden of TB (8–10 percent households) than the Prime Minister’s Grant (PMG) colony which had 1 percent of households despite similar socio-economic profiles of people. Our study showed that the majority got TB after they moved into these colonies. The doctors had a hunch that TB had something to do with the built form and this association was established through the study. Although all three colonies were dense, the open space and light and ventilation conditions in both Natwar Parekh and Lallubhai Compound were way worse than in PMG Colony.

The IIT-B team precisely captured this through daylight autonomy, sky-view factor, and similar data – hence I would not like to single out density as a singular factor. The question is: Was this just bad architecture by ill-informed architects? No, these buildings were mandated to be built badly; it’s to do with the economics of redevelopment.

How were these buildings mandated to be built badly?

There are design mandates that architects follow—the National Building Code on optimum light intensity, ventilation, fire safety and so on are used as a guideline to develop a city’s Development Control Regulations (DCR) which is statutory. The DCRs tweak the NBC guidelines to the cities particularities. They provide mandates for distance between buildings, building heights, window size, open space, and so on. These norms originate from particular histories of contagion in our cities.

For example, the Bombay plague of 1896 brought attention to the light and ventilation within the native city, the suburban colonies that were built in its wake adopted the 63.5-degree rule to allow houses get adequate light and ventilation, later this translated to the H/3 rule. This means if a building is 24 metres (H), there should be 8 metres (H/3) around it for sunlight to come in; two 24-metre buildings should have 16 metres between them. Eventually regulations were also crafted for sizes of window in different climatic zones, amount of open space requirements, and of course number of units per hectare, which influences the density of a place.

We realised that the PMG Colony was built with general regulations and applied the H/3 rule. However the other two colonies were built with SRA regulations which relaxed the distance between two 24-metre tall buildings to 3 metres between them, which is why these buildings are so tightly packed. What is the logic behind this? As we know, the SRA is based on a cross-subsidy model. Slums that are usually one-two storey tall are re-housed into tall rehabilitation buildings and the rest of the land is opened up for market development. The developer gets prime land for free and, in exchange, develops the rehabilitation housing. The regulations do not fix the amount of land to be used for rehabilitation housing.

Now, governments want to provide the largest number of houses to the poor, displaced, project affected people. Developers want to use minimum land for this housing and keep the maximum for market development. By reducing the distance between SRA buildings, decreasing open space, increasing unit density, the norms seek to build the largest number of units in the least amount of land. These relaxed norms may make the SRA scheme viable but it also exacerbates the incidence of TB.

You say that density is not the only factor in TB in the SRA buildings; light and ventilation are too. But is the lack of light and ventilation itself not an outcome of density?

Let’s take a moment to understand “unit density”and its relationship to building type. A tall building with a small footprint (ground cover), larger plot open space, can have a density that is similar to a squat building with a very large footprint. If designed right, there is a higher probability of light and ventilation being better in the taller building than the squat building with the same density. But we don’t like going very tall in the case of low-income housing because that leads to higher maintenance burdens on the inhabitants. So, we balance and optimise these factors.

Now let’s come to the example of the three buildings in our study. Firstly, the “net unit density” is high for all three buildings. The NBC Code says that low-income housing should have 500 dwelling units per gross hectare as maximum density (gross hectare takes into consideration open space, etc). Mumbai’s DCR requires 650 dwelling units per net hectare as minimum density-–already worse than the NBC norms.

The PMG Colony has some 900 dwelling units per net hectare while the Natwar Parekh and Lallubhai Compound are at approximately 1,100 dwelling units per net hectare. Yes, the two are denser than PMG Colony but PMG Colony also qualifies as high density housing. The difference is that it is better designed with adequate distances between buildings, and surrounded by roads that allow better light and ventilation. In other words, at neighbourhood level, its gross density is lower.

How do these factors affect women and other genders not just in terms of TB but other issues?

The study notes that females of reproductive age group are specifically affected by TB. But I haven’t studied this spatially in detail. It requires a different set of methods to establish this scientifically, but I did see, in these buildings, as in our society, that women spent more time at home and had lesser access to open space. Logically, I could say that people who remained indoors with those suffering from TB had higher susceptibility to the disease. This includes – women, the elderly, and children.

The study showed that the quality of the built environment matters to the incidence of TB. What else can we take away from it?

For a scientific paper, it is essential to have measurable terms such as the sky-view and daylight factors but these are also visible to the naked eye. When you are in that space, you can see there’s no light, you are uncomfortable. Architects do study what makes comfortable form for different climates. With the advent of new modelling technologies this can be taken a step further to understand if the new building typologies being developed for denser living provide adequate light and ventilation. This can inform our norms, going forward. But norms cannot be arbitrarily relaxed for one group of people, especially the vulnerable people, and upheld for others just for the sake of financial feasibility. What’s good for a person in a regular housing colony is good for a person in a SRA colony.

How did the study help in governments or authorities addressing the issue?

At that time, the new DCR was being formulated in the wake of the Development Plan 2034. When suggestions and objections were invited, we made a plea that the SRA buildings should not have different regulations and argued for healthy uniform regulations. I think the study raised awareness because people had not thought about built form and disease this way, but the problem was not sufficiently addressed. There was a change in the distance between buildings from 3 metres to 6 metres but the building height also changed from 24 to 36 metres. So, proportionately, it didn’t make much difference. Also, these relaxations and changes are made arbitrarily without much scientific analysis which makes me uncomfortable.

Density norms or building norms are laid down by governments. What specifically do you want to see governments do in Mumbai or elsewhere?

Remove the minimum unit density of 650 per net hectare. Work backwards from the examples of good light and ventilation buildings that are not more than 8 storeys tall, have a unit size of 300-400 square feet to understand what could be a good unit density per hectare for affordable housing in Mumbai, and establish a maximum unit density at net and gross levels. I am not saying it has to be the NBC standard but it has to be substantiated through analysis. Secondly, understand that low-income buildings have a higher number of people per unit and if we are creating affordable low-income housing, there must be infrastructure and open space to support it in some way. The maximum density norm allows me to hold the state accountable for a certain degree of infrastructure provision. This is why I find it useful.

What are your recommendations to improve the livability of the SRA buildings?

For the existing buildings, I suggest retrofitting. Add artificial ventilators, make outdoor spaces in the area better so that people can spend more time outside. I don’t recommend pulling down these buildings because I don’t know what fate awaits inhabitants if this action is taken. They put so much trust in us, gave data, and if the result is their buildings pulled down without better houses in return, it is wrong and unethical on our part. That’s why I say retrofit but that’s not an ideal solution. That’s the conundrum. As a planner, my plea is ‘don’t build like this’. It traps people in bad built forms.

How would you reflect on the climate crisis and high density living for the vulnerable people? What’s the way forward?

We have trapped vulnerable populations in housing that is extremely inadequate to withstand climatic challenges of the coming years. As my friend Lubaina Rangwala articulated, this is a kind of infrastructure lock-in – a word usually reserved for large infrastructure projects. There is no green open space in these colonies or even in their neighbourhoods. Heat Island effect from asphalt and concrete makes it unbearable in summer. People can’t afford air-conditioning and related electricity bills, they already have lights on even during the day to compensate for the lack of sunlight. Can you imagine living here for the next 40 years? That is usually the estimated life of concrete SRA buildings.

I remember Dr. Ravikant Singh was asked once in a conference, isn’t this better than a slum. He quipped: “Slum main cholera hota hai, yahan TB hota hai”. I understand this. I wouldn’t undermine the importance of the attached toilet in these buildings and the benefits it brings. But shouldn’t formal, legal, state-provided housing aim for a better future for its residents than to have them pick between diseases?!

The way Mumbai is growing, do planners want to build better to bridge the divide between the better-off and the poor?

I feel that urban planning, as a profession, has fallen into a place where we work within a set of constraints; what’s around us is the product of those constraints. This is basically the government pulling out of building affordable housing and telling builders to give free housing through the cross-subsidy model. How many of these constraints are artificial and how many real, is the question. When Mumbai’s municipal corporation, which has thousands of crores in deposits and the money to build the coastal road to serve 7 percent of the population that has cars, says there’s no money for urban housing, it is unbelievable. Does it have to be dense housing? I think so. Does it have to be this dense? No. Outside Mumbai, cross-subsidised slum redevelopment is not a concept yet. This is entirely a Mumbai story, a horror story.

All photos: Namrata Kapoor