The mercury inches up, the days get longer and warmer, and mango pyramids line roads and shops everywhere. New school books and uniforms are purchased for the next academic year. Schools shut down and holidays commenced. In the 1990s, summers were about friends who came knocking on doors, pocket money spent on cold drinks, unstructured and unbridled play, sometimes indoors but primarily outdoors. Street tournaments took on great seriousness in every nook and cranny of the city, windows were broken, trees were conquered, fruits stolen, and knees and elbows bruised.

What do summer holidays and school breaks look like for adolescents in 2025 in Bhubaneswar? Nothing like in the 1990s or the decades before that. Adolescents find themselves barricaded or squeezed out of what once were natural play spaces, priced out of activities that once were affordable. Listen to these voices.

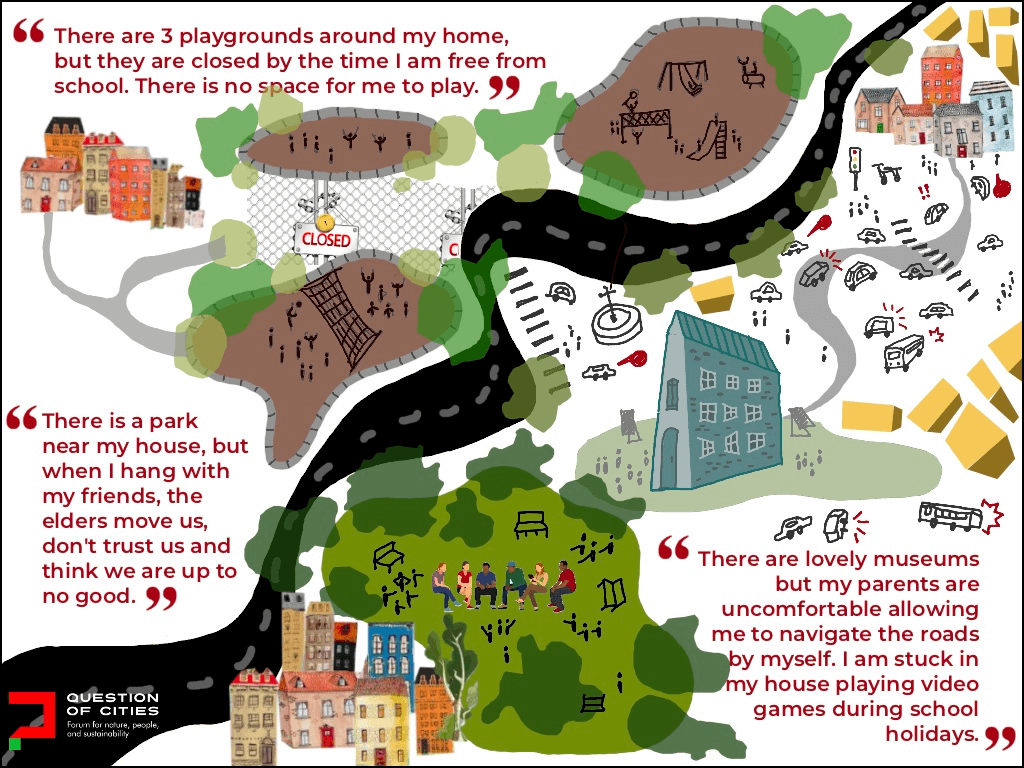

“There are three playgrounds around my home, but they are closed by the time I am free. There is no space for me to play,” says a 13-year-old. “There is a park near my house but when I hang out with my friends, the grandfathers and grandmoms move us, the aunties don’t trust us, and the uncles think we are up to no good. The gym and play equipment don’t work for us. So where do we go,” asks a 15-year-old. “There are lovely museums and parks but they are inaccessible by bus and my parents need the car. They are uncomfortable with me navigating the roads on my cycle or in an auto. I am stuck in my house playing video games during school holidays,” laments a 17-year-old.

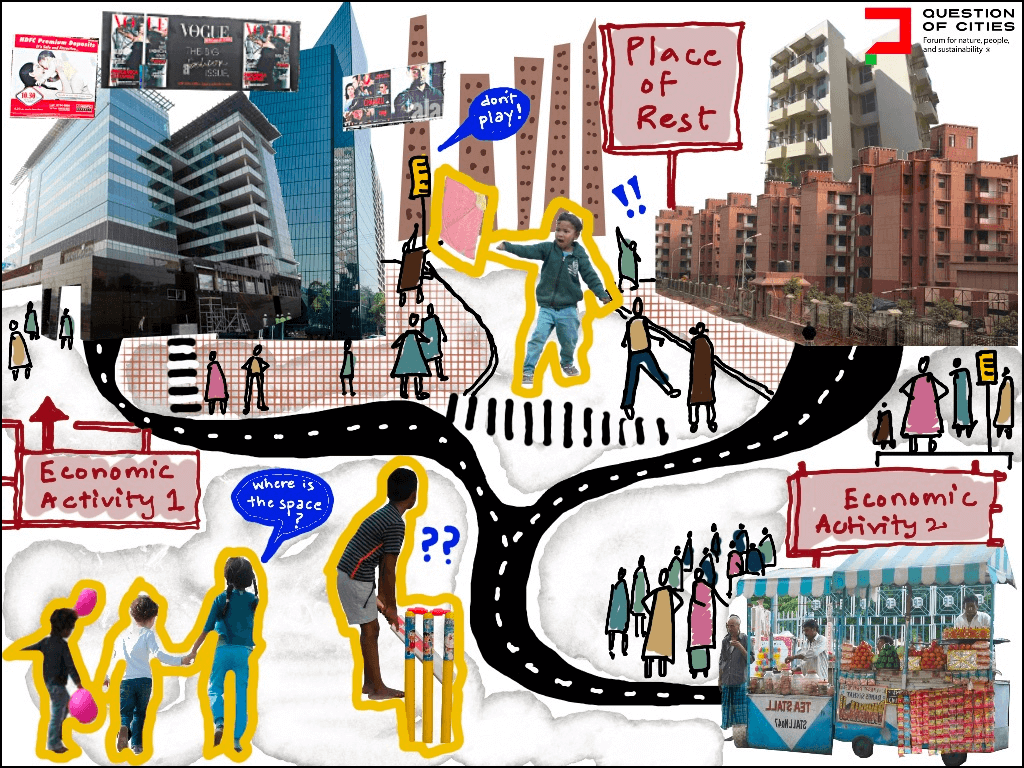

Urban spaces are currently spaces of adult hegemony, as the illustrations by Nikeita Saraf show. They are designed to facilitate the economic capacity of the adults, moving them from one space of economic activity to another space of economic activity before they rest and recuperate at their homes. What about them, they who will inherit this city, who are neither a vote bank nor income earners now, but call it home? What about those whose socio-cognitive and physical development is determined by the environmental cues from the city and its design?

How does the city cater to their needs? City planners and makers rarely pause to ask this question of themselves.

Right to play as a fundamental right

“Now and then, it is good to pause in our pursuit of happiness and just be happy,” remarked Guilame Apollinare[1]. Our built environment hardly allows us spaces and moments to pause in this pursuit and just be happy. Or for children and adolescents to just play to learn about life, to discover themselves, make connections.

The idea of play is rooted in choice, in freedom, in agency. It could be structured or an unstructured exploration of space, time and the self. In either, it is something “freely chosen, personally directed, and intrinsically motivated,”[2] drawing from the environment around, and essential for cognitive, physical and psycho-social development in children. Play helps decompression, stress-relief, and emotional regulation in adults too. Play is how humans wire and rewire the brain to allow its creative and unbridled expression.

Fundamental to the idea of play is agency and choice. Space and the built environment have a lot to do with how children and adolescents play. This underpinning of “freedom of choice and agency” is why the right to play has been recognised as a fundamental human right, enshrined in Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1980). Like many such statutes, it has remained on paper even as cities in India, including Bhubaneswar, get busy with development.

Play takes on many forms-–attunement play where new connections are established between people or between people and places, creative play where imagination is used to transcend the current state, social play where connections with others are built, guided play where one takes on structures and roles guided by others, and independent play. In every form, the underpinning idea is to suspend the cares of the day-to-day world and use the opportunity for physical, cognitive, sensorial and intellectual development, social connection, and well-being. A study of urban public open spaces in Denmark[3] identified that just the passive experience of watching children play creates a pleasant multi-sensorial experience for adults that helps shape a positive view of life.

Urban spaces and play

In the urban context, safe, supportive, stimulating social environments that support play as the foundation of healthy physical development can – and must – be built. These do not come about naturally like the trees and open spaces we used to play in; they have to be deliberately planned, designed and constructed. The way cities are designed today is suited neither for a growing and aging population nor for the needs of children and adolescents.

As urban landscapes and microclimates change drastically, outdoor urban environments which include streets, plazas, market places are becoming increasingly inhospitable to children and adolescents. We have moved away from the template of cities that incorporated playfulness in their form and shape with chowks and plazas, winding streets, porous front and back yards, and other spaces where play was possible. Increasingly, play areas are designated and, worse, kept locked under the supervision of security guards.

When cities moved away from shared spaces where children and adolescents hung out on walls and under trees, we moved away from playfulness and freedom too. We acknowledged only the constraints of everyday life, we built spaces that prioritised cars and individual transport systems, eroding even the people-to-people connection that happens in public transport.

India’s cities are fast resembling the world where nearly half of the world’s parents have no time to play with their children[4] and a little more than half of the children[5] play outdoors for less than an hour a day. Recognising this, UNICEF launched the Child Friendly City Initiative (CFCI) in 2018 and included the right to family time, play and leisure as key components of its framework. In the same year, Bhubaneswar launched a partnership with Urban95 to promote well-being for children. Central to the concept is providing “accessible, safe and inclusive public spaces” and designing experiences at “95 centimetres” which is the average height of a 3-year-old.

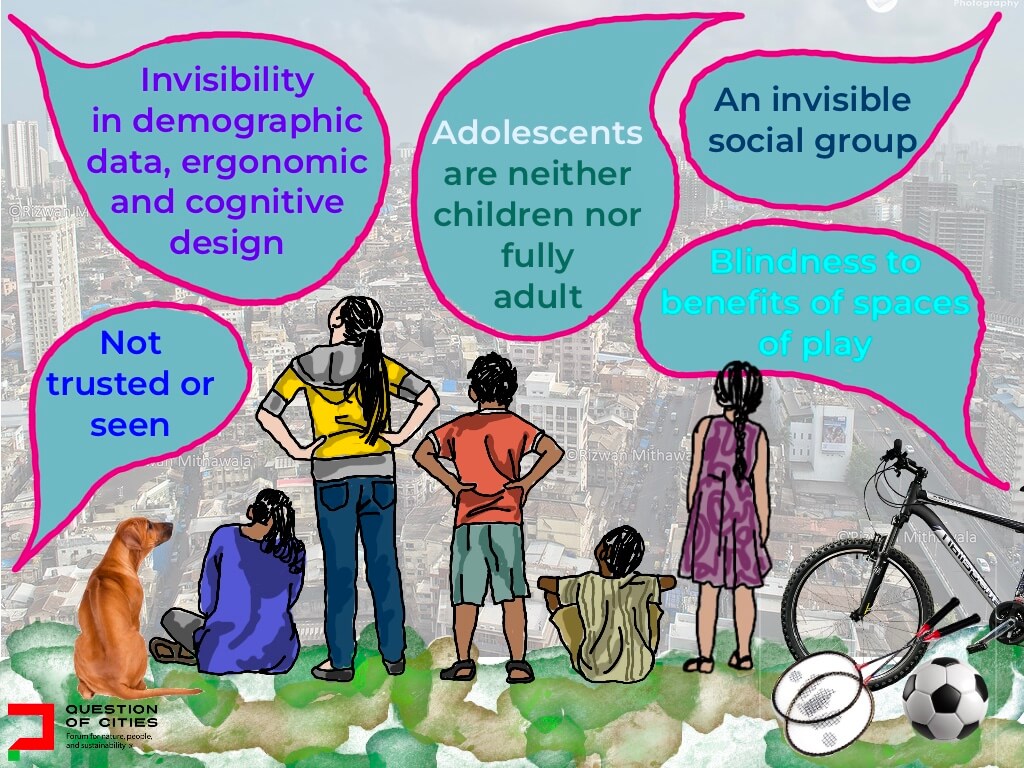

Adolescents, the invisible group

Adolescence is a period of rapid physical, cognitive and psycho-social growth. However, in the idea of play, adolescents or those between 10 and 19 years tend to get left out. An article in the American Journal of Play[6] highlights the decline of play as one of the primary reasons for rise in depression and a declining mental health of adolescents. The need for play and playfulness in adolescents is different from that of children and adults, but adolescents are an invisible social group when it comes to designing cities and spaces.

This socio-cultural invisibility extends to ergonomic and cognitive design, in spatial planning and the design of open spaces for play and recreation. Adolescence is as much a socio-cultural construct as a physical and development construct. Very little has been done even the world over to recognise and research adolescents as a unique social group, especially with respect to play. The earliest intersection of urban environment and young people was Kevin Lynch’s research in 1977.[7]

The next leap came nearly two decades later, by a UNESCO reinstatement of his research. The Covid-19 pandemic brought this to the forefront again.

According to the World Health Organization[8], one in every six humans worldwide is currently an adolescent. India is home to the largest adolescent population in the world—253 million.[9]

Overlaid with factors of caste and gender, the vulnerabilities increase. Adolescence is anyway a period of intense vulnerability. At their age, play becomes essential for inter-personal interaction, socio-cultural learning, building autonomy, and forming healthy behaviours. Their play spaces are also the primary point of entry to explore their cities and environments. Not paying attention has cost us dearly already.

A 2024 Ireland study found that adolescents “clearly stand out as under-resourced or under-facilitated” with adolescent girls more underserved than boys in the allocation of play spaces.[10] Adolescents playact socio-cultural connections, even communicate with adults through play. As they stand on the threshold between childhood and adulthood, the lack of provision of spaces is pushing them into devices which experts say leave them “connected, but alone”. Many adolescents in low-income families are forced to also shoulder adult burdens. Which spaces in our cities just allow them to be, to loiter, to understand the world on their terms?

Children’s play spaces are too childish for them, adult fun spaces (mostly private) do not welcome them. If they have to learn to navigate their environments, autonomy, decision making, build a sense of identity and a sense of belonging, what in our cities or city-making supports this? Very little. Our built environments must encourage their free play and independent mobility, allow them to anchor themselves but also build connections to others.

Bhubaneswar’s first steps

Research by the Real Play Coalition[11] and the Resilient Cities Network highlights the potential that play offers to unlock broader socio-economic and environmental benefits.[12] A network of interconnected play spaces or intermediate spaces from household to building and neighbourhood level to the city level can be built to offer adolescents agency, power and engagement. How good it would be if these could be reconfigured from existing ones with meaningful participation from them?

The recent Bhubaneswar Municipal Corporations programme, as a part of the Safe Vibrant and Healthy Public Spaces project, is the first step. Adolescents from varied walks of life were familiarised and empowered to understand public spaces, then assess them through a structured and actionable framework. The results were then translated co-creatively into two tactical interventions as proof of concept of how adolescent-led reconfiguration of public spaces would be.

This took the form of a ‘model adolescent hub’ in front of Rajdhani College and ‘Sensephere’ at Bhima Bhoi Street where sensorial cues were included to facilitate independent mobility for persons with varied abilities. As adolescents took the lead in designing environments for their needs, there emerged a mechanism for meaningful, participatory and inclusive development of public spaces that met their needs-–and the spaces became inclusive.

These initiatives provide a beacon of hope that an equitable and playful city, designed by adolescents alongside the usual stakeholders – development authorities, community and political leaders – are possible. They are an opportunity to create spaces where play becomes an integral part of daily life and open opportunities for new forms of interactions, expansion of techno-physical innovations, and forge deeper connections between people and places.

If we all have “the power of choice in determining who we ultimately become,”[13] as motivational speaker Chris Gardner remarked, then adolescents in our cities must have that opportunity too – and we city-makers have to provide it for them.

Virajitha Chimalapati, a conservation architect and an oral historian by training, is currently pursuing her PhD at the University of York. Based in Cuttack, Odisha, she researches the role of culture in co-creative, inclusive and equitable climate policy operationalisation, and is a Senior Research Analyst in World Resources Institute, India. She is passionate about systems thinking and framework/process-led solution formulation for co-creating inclusive urban environments.