It is customary at the end of a year to look back and take stock of the work or progress done and work that did not happen. On cities and urbanisation in India, there is much to be disappointed about. The stocktake is elsewhere in this edition. However, the emphasis at Question of Cities is to look ahead and reimagine an urban India from our perspective on nature, people, and sustainability.

Our belief is that the future lies in nature-based planning and making of cities, that cities should be not just cities for all but especially for the vulnerable, and that we must be watchful of the process of urbanisation. While it is important to get the details right across cities – such as climate action plans, walking infrastructure, affordable public transport and amenities, adequate affordable housing, sustainable building codes, municipal finances and more – it is critical to identify and articulate the trends and ideologies deeply influencing the way cities are being built.

There are three trends that Question of Cities will be critically watching – and reviewing – through 2025. Firstly, the attempts by planners and governments to impose uniformity in every sphere of our lives, across communities, places, and the environment needs scrutiny. It is an attempt to undermine the diversity in our cities, including the diversity of opportunities and choices people make, diversity in the built environment, diversity in how city spaces are claimed and used.

The second trend Question of Cities will be watching is the rapid erosion of public property to facilitate privatisation at the cost of larger public good. This undercuts at the very basis of a dignified urban life and imperils the concept of citizenship. What rights and how many rights can people in cities claim, let alone enforce or enlarge the idea of the Right to the City, if the public domain shrinks over time to allow larger and larger areas or services to be owned or controlled by private entities?

And third is the rampant destruction of natural ecology, the loss of biodiversity, and the climate crisis threatening our health and well-being, most of all of the vulnerable and marginalised communities but of everyone who lives and works in cities. Question of Cities will closely follow various impacts that these inter-connected phenomena have on people, the built form, and the environment. We will document and review the many ideas, events, activities, struggles, interventions, dialogues and writings that offer or practise alternatives to achieve equity, justice, and pluralism, and the way we can renew our relationship with nature for sustainable cities.

This last aspect – how human beings, especially people in power, renew and reinvigorate the human-nature relationship – will be the single-most determinant of the cities of our future. Cities now, we argue, are physical spaces planned and built with deliberation and investment to suit exclusive interests, in the process of which nature or the environment is largely fractured and diminished. This is far from ideal. Cities must be built in nature, with nature. And this must be ingrained in the fields of urban planning, urban design and construction. The era of business-as-usual is past us; cities, built spaces, that disregard nature and remain stubbornly agnostic to climate change are doomed.

Urbanisation, on the other hand, is a larger, more complex and continuous process of development rooted in ideas of freedom and equality, a process that carries the potential to collectively liberate and transform people’s lives, values and aspirations which, in turn, positively transforms the urban space. Jan Gehl, the well-known architect and urban designer, speaks for us when he stated: “First we shape the cities – then they shape us”.

The argument is that this process, which the three prevailing trends influence, needs a close watch – not by us only, or planners and urbanists, but by communities and people in every city. These, besides our regular perspectives, essays, photo and ground stories on natural and built environments, climate change, gender, movements and more are on our Agenda 2025.

Concerns about imposed uniformity

Cities are a melting pot of diverse communities, ways of life, opinions, choices, accesses, rights reflected in the varied and entwined spaces and structures. Yet, new developments in cities or new cities display a cookie-cutter style uniformity in scale, designs and layouts. Also, uniformity in who is included in the shining new spaces and who remains in the margins. This is largely imposed, centralised, by the ruling dispensation. Over time, this has become a subtle but powerful attempt to undermine diversity; it may well deny the idea of cities itself, the extent of their urbanity.

Recent trends of urban development plans and policies have attempted to over-simplify urban complexity with the imposed oneness. Somehow, wrongly, to be one is to be equal, is the popular political call now. This not only undermines the essence of equality but a uniform way of life and built form in a city is a dangerously misplaced way to urbanise. The imposition of uniformity takes various forms.

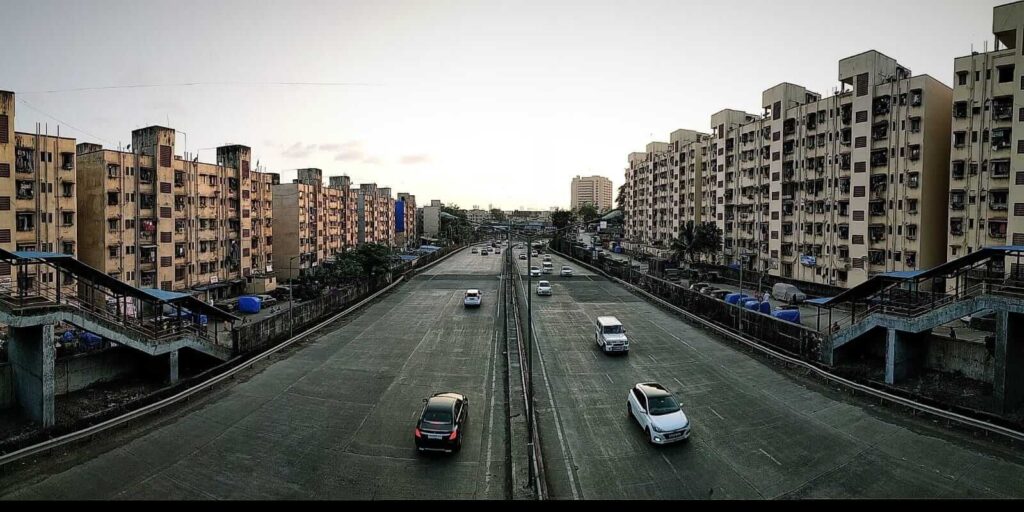

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Mumbai’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) model is an excellent example. Irrespective of the socio-economic dynamics on the ground, work done by slum dwellers, their needs and aspirations, the SRA prescribes a uniform housing-building mode. Mumbai’s landscape is increasingly defined by a uniform building typology—standardised, repetitive and rigid.[1] Across India’s large cities, the commons now include a carefully ‘constructed’ and barricaded garden with standardised spaces for walking or jogging and the garden shut for the better part of the day. Bengaluru’s citizens mobilised a movement to have these opened during intensely hot summer afternoons this year.[2] These manicured and highly controlled gardens capture open spaces but offer no unrestricted space or fluidity of use as maidans do.

Gurugram, as most new cities, has copy-paste building complexes, all attempting to showcase a uniformly warped sense of modernity. ‘Tall buildings, industrial or commercial estates, retail parks, new transport systems and business districts’ are some of the features of uniformity that do not take into account diverse local geography, culture and conditions, according to this study.[3] The Maharashtra government, in 2017, sought to bring uniformity of Development Plans of all cities in the state disregarding the unique character and special circumstances of each but it had to be shelved.[4]

Imposing uniformity in the urban space is the essence of neo-liberal politics that assures and actively facilitates the free-market approach to development. For the powers-that-be, achieving uniformity means greater authority, control, production monopoly, limited access, and an upper-class-oriented model designed to exclude the vast majority of people from access to basic services in a city, including formal housing and amenities. The SRA model, for instance, creates a landscape that’s homegenised, curbs people’s rights of participation in decisions that affect their lives, and restricts the city to one standard model promoted by private entities for ease of production and maximisation of profit. Urbanisation, and the larger public good, are completely ignored.

The juggernaut of privatisation

Cities have been, and are being, rapidly privatised. In the name of development, public land and resources are being gifted away, either free or at nominal prices, to private entities and, especially a handful of conglomerates, in housing, amenities, transport, and open spaces. Natural areas too are not spared. Gated complexes to private cities, they are all around us. Such a city, Sarah Moser, an associate professor of geography at McGill University who has extensively studied the global new city movement, termed “a kind of like a giant mall”.[5]

The privatisation trend may have begun in the previous decade but it has gathered momentum in the past few years. As the redoubtable journal Economic and Political Weekly pointed out in its editorial in March 2010: “The call for public-private partnerships was taken up ahead of the 2010-11 Union Budget by one of India’s largest real estate developers, who argued that the state should leave the tasks of ‘conceptualisation and execution’ of urban development to private players. Nor is the paradigm of private cities merely a demand on paper.”[6]

Photo: Raghav Gupta

Successive governments have rolled out policies that covertly destruct and deplete public property, thereby colonising a city in a new avatar. Public parks like Bengaluru’s Cubbon Park are displaying this trend. Park authorities recently disrupted a silent public reading[7] and demanded that people take permission. What’s the point of a public space if people cannot come together without official letters?

Housing sector movements in Mumbai like Nivara Hakk in pre-1991 liberalisation era, comprised people’s protests to government offices and elected representatives;[8] in the post-liberalisation decades, the few protests that take place, or memorandums of demands, have been to offices of real estate entities and builders’ offices tasked with ‘development’ work. Politically, there has been a shift from people demanding their rights to negotiating benefits or frills from builders.

The rapid decline of democratic values and ethos, under which ironically privatisation flourished has been normalised. We are at a point where even when swathes of public land are transferred, free of cost, to private developers, the protests are not at the scale or intensity that influence change.

Photo: QoC File

There’s no Alt Eco

The privatise-and-construct-more development has come at the cost of disrupting and destructing the balance in nature. Government agencies think nothing of permitting private entities to tear into the ground and go deep down, often four-five floors below earth, to construct buildings that are opaque mono-blocks of glass and concrete, without any ground space for trees or rainwater percolation. The advertisements of ‘homes in the sky’ or ‘infinity pools on exclusive terrace’ do not say the real cost, the environmental cost, of such fancy constructions.

How deep is really deep beyond which nature will begin to backlash? How is the rising sea level in Mumbai and other coastal cities, or the increasing impacts of climate crisis — cyclonic winds, floods, rising temperatures, heat island effects – that affects all cities factored into constructions? Where are the urban forests and how are tree covers being protected? How many ridges can be hived off to make more buildings? This should be a no-brainer but it needs to be repeated – without nature, cities cannot be. In fact, going forward, cities must be planned and designed in alignment with nature.

The discussions and books and movements about nature in cities must now begin to reflect on the ground. Climate change impacts every aspect of urban life every year – millions of outdoor workers suffer (or die) in intense heat,[9] lakhs of poor households are threatened by urban floods,[10] millions including children battle health setbacks from respiratory issues to reproductive problems in women as a result of air pollution. Scientists at the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES),[11] have called for “fundamental and transformative shifts” in how people interact with the natural world.

Building more by destroying nature – trees, forests, hills, rivers, lakes – will exacerbate the extreme weather impacts. This is critical because estimates are India’s urban spaces will have nearly 700 million by 2050. The urbanisation so far has extracted a heavy price of wetlands. India lost “nearly one-third of its natural wetlands to urbanisation, agricultural expansion and pollution” over four decades till 2014, a study by non-government organisation Wetlands International South Asia (WISA) found in 2020.[12] Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Bengaluru have lost the maximum wetlands – from 50 to 70 percent – due to nature-damaging urbanisation.[13]

The Right to the City, a movement which must be mobilised and given momentum, will be limited if it does not include the right to the environment, clean air and water. Drawing up climate action plans, heat action and flood plans, is no longer enough as they seek to minimise the climate impact after destroying nature’s balance. A more sagacious way should be to build cities in nature, keeping ecology at the centre of urban planning and construction. The nature-people relationship, segregated over time, must be renewed or repaired. The new transformative approach, the IPBES report stated, “must be based on four fundamental principles—equity and justice, pluralism and inclusion, respectful and reciprocal human-nature relationships, and adaptive learning and action,” as environmental journalist Amitabh Sinha pointed out.[14]

This, at the minimum, is the Question of Cities’ agenda for 2025.

PK Das is an urban planner, architect and activist with more than four decades of experience. He has been working to establish a close relationship between his discipline, urban ecology and people through a participatory planning process. He has received numerous awards including LSE Urban Age award and the prestigious Jane Jacobs International Medal for his work in revitalising open spaces in Mumbai, rehabilitating slums and initiating participatory planning process. He is the founder of Question of Cities.

Cover photo: Jashvitha Dhagey