Climate change has been affecting livelihoods, threatening a range of human rights including those to life, water and sanitation, food, health, and housing. There were 573 extreme weather, climate and water-related events in India leading to the death of 1.38 lakh people between 1970 and 2021, according to the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD).

In the first nine months of last year, the country experienced extreme weather events almost every day or had extreme weather on 86 percent of the days, a report by the independent think tank Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) showed.[1] The “State of India’s Environment 2022” report states that India is the fourth most affected country in the world by climate change-induced migration and estimates that 45 million people will be forced to migrate from their homes by 2050 due to climate disasters.[2]

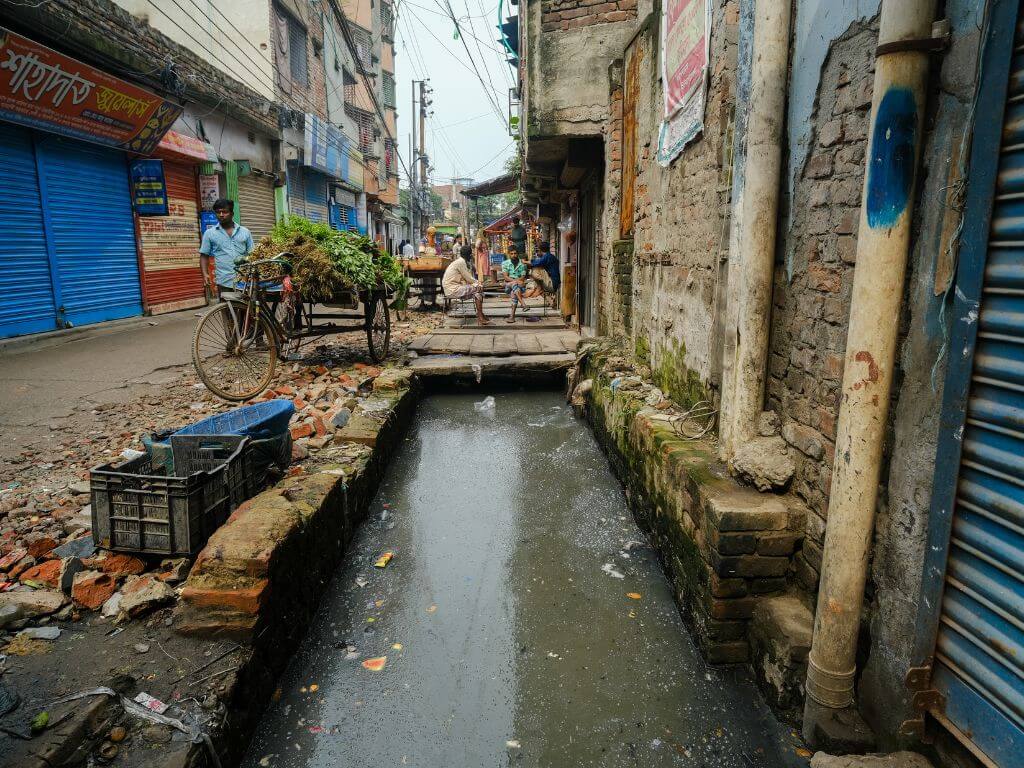

As climate change disproportionately affects vulnerable and marginalised communities, threatening their lives and destabilising livelihoods, the need to recognise that climate action has to include rights was never greater than it is today. Climate adaptation and mitigation efforts without a strong lens on rights and justice built in may further destabilise the vulnerable people. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres remarked: “Climate change is happening now and to all of us. No country or community is immune. And, as is always the case, the poor and vulnerable are the first to suffer and the worst hit.”[3]

Climate justice, not merely climate action, becomes important. It urges fair and equal environmental decision-making. Countries that became wealthy through unrestricted climate pollution have the greatest responsibility to not only stop global warming, but also to help other countries adapt to climate change and “develop economically with non-polluting technologies”. Climate justice mandates that, within countries and cities, the vulnerable receive the financial support and have access to robust infrastructure needed to combat climate impacts.[4]

In South Asia, home to a vast population of poor and migrating populations, climate justice is particularly relevant. “Climate justice acknowledges that certain groups are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change and seeks to address these inequalities within all climate action…Climate justice requires climate solutions grounded in human rights, equality and non-discrimination and the participation of those most-affected. This must include accountability for polluters, redress for victims, and protection of the vulnerable in all prevention, response, mitigation and remedial measures.[5]

There is a gender angle too. In Pakistan, “the UN estimates that 80 percent of the people displaced by climate change are women. Last year’s devastating floods alone left almost 650,000 pregnant Pakistani women deprived of access to healthcare, forced to give birth under the open sky. The relentless floods also left eight million girls and women without access to basic menstrual hygiene products and toilets to manage their period. As gender-based violence exacerbates in the wake of climate crises, girls are increasingly being traded off into child marriages in return for food amidst climate-induced starvation across the world. Climate change, then, is not just an environmental phenomenon, it is a social injustice crisis that aggravates already existing injustices in communities. It is for this reason that any discussion on climate action is tokenistic in nature and futile in structure, unless it addresses the plight of women in climate crises.”[6]

Photo: Rajib Dhar

Principles of climate justice

A report by the Mary Robinson Foundation, named after the pioneering woman who was president of Ireland and then served as the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy on Climate Change and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, offers a framework for climate justice. She called climate justice “a man-made problem with a feminist solution”. Some of the cornerstones of the framework are:

1. Respect and protect human rights

The international rights framework provides a reservoir of legal imperatives to frame morally appropriate responses to climate change, rooted in equality and justice. The idea of human rights points societies towards internationally agreed values around which common action can be negotiated and then acted upon. The guarantee of basic rights rooted in respect for the dignity of the person which is at the core of this approach makes it an indispensable foundation for action on climate justice.

2. Support the right to development

The vast gulf in resources between rich and poor, evident in the gap between countries in the North and South and also within many countries (both North and South) is the deepest injustice of our age. Climate change both highlights and exacerbates this gulf in equality. It also provides the world with an opportunity. Climate change highlights our true interdependence and must lead to a new and respectful paradigm of sustainable development, based on the urgent need to scale up and transfer green technologies and to support low carbon climate resilient strategies for the poorest so that they become part of the combined effort in mitigation and adaptation.

3. Share benefits and burdens equitably

The benefits and burdens associated with climate change and its resolution must be fairly allocated. This involves acceptance of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities in relation to reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Those who have most responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions and most capacity to act must cut emissions first.[7]

The IPCC reports

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has so far published two instalments of its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). While the first report, released in September 2021, unequivocally attributed extreme weather events to climate change, the one released in February 2022 laid bare that inequality makes certain communities and countries more vulnerable to climate change impacts. In this report, the IPCC for the first time authoritatively stated that climate justice now needs to be at the centre of global policy-making.

The report, ‘Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability’ compiled by 270 authors from 67 countries, incorporating research from over 34,000 scientific papers, identifies 127 risks to natural and human systems and notes that nearly half the global population now lives in settings that are “highly vulnerable to climate change.” However, climate change disproportionately affects marginalised groups, amplifying inequalities and undermining sustainable development across all regions, it states with “high confidence”.

“The poor typically have low carbon footprints but are disproportionately affected by adverse consequences of climate change,” it states, adding that they lack access to adaptation options. The report identifies that the most vulnerable regions are located in Global South — East, Central and West Africa, South Asia, Micronesia and in Central America – which reel from high levels of poverty, inadequate access to basic services like water and sanitation, gender inequalities and poor governance.

The report states: “In this regard, specific attention ought to be paid to how responses to climate change exacerbates inequalities within societies and creates tensions between different groups — typically between those who are able to protect themselves from climate change impacts and those who do not have sufficient resources and/or are not prioritised in the responses to climate change.”[8]

Photo: Dipen Dhungana

Climate Change and Conflict Resolution in South Asia’s Highlands

The report highlights how South Asia’s northern highlands have the potential to spur regional dispute resolution mechanisms through concerted joint-climate action. While initial US studies showed water scarcity as a threat capable of causing intrastate conflicts along ethnic lines, recent reports showed concerns about states using transboundary river basins as “leverage over their neighbours to preserve their water interests.” Caution has been sounded about “medium risk” of cross-border water tensions and conflicts through 2030 while “high risk” is predicted through to 2040. Pakistan, India, and Afghanistan have been identified as highly vulnerable countries of concern.

There is a dire need to prioritise climate preservation efforts as rising sea levels, climate refugees, and water wars are expected to put additional demands on US diplomatic, economic, humanitarian, and military leadership. The preservation of mega glacier bodies and sustainability of the highlands is crucial to contain floods, sea rise, climate migrants, and direct confrontations over water, states the report.[9]

The case for reparations

This paper examines the human rights dimensions of the problem, placing it within a climate justice context. The critical question considered is this: What role should high-income countries undertake in meeting their obligation to not only significantly reduce and mitigate their current emissions of greenhouse gases but also to make reparations for the harm their emissions, both historically and at present, have inflicted on low- and middle-income countries.

This paper also identifies which parties are most responsible for the current global climate crisis, both historically and currently, and should therefore fund the largest proportion of climate-related reparations. “Climate change will make women’s responsibility for gathering water, food, and fuel for their households in poor countries more difficult. Because the lives of indigenous people are so closely tied to the natural environment, they are likely to suffer both disproportionate physical loss and a sense of spiritual loss and a lack of well-being. People who will be particularly susceptible to the health consequences of climate change also consist of many of the vulnerable groups of concern to the human rights community: those who are poor, members of minority groups, older people, people with chronic diseases and disabilities, and workers exposed to extreme heat,” the paper points out.

Moreover, individuals from these communities will lack the resources to adapt to and cushion the blows from climate change. “There is thus concern that the intranational socioeconomic disparities between affluent and disadvantaged groups due to the impacts of climate change may enter into a self-reinforcing vicious circle, whereby the initial inequality will result in disadvantaged groups suffering disproportionately, leading to greater subsequent inequality,” it states.[10]

Photo: Zofeen T Ebrahim

‘Climate justice in India’

Edited by Prakash Kashwan, the book Climate Justice in India covers a wide range of topics starting from energy democracy, the intersectionality of access to drinking water, agroecology and women’s land rights to national and state climate plans, urban policy, caste justice and environmental and climate social movements, and has a collection of insightful and well-researched articles by scholars and professors.

Collectively, the writings raise the primary question of unequal effects of climate change and of climate action, with the goal of bringing this into ongoing scholarly and policy debates on climate change in India. They call for moving beyond the existing debates about international versus domestic climate justice to examine the complex ways in which international and subnational policies, programs, and resource mobilisations intersect to shape the outcomes of climate action and climate justice.

An analysis-based chapter by Eric Chu and Kavya Michael shows that despite Indian leaders identifying local development priorities as the main entry point for urban climate mitigation and adaptation, market actors often assume control of these opportunities, leading to the exclusion of much of India’s urban population. “The lower-middle class and income-poor urban residents that are often substantively excluded from urban climate plans also fuel India’s vast informal urban economies. Part of this exclusion has to do with the centralisation of decision-making within urban local government bodies, as elected ward representatives and residents are rarely consulted in urban policy-making.”[11]

Cover photo: Saqlain Rizve