“A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transportation.”

Gustavo Petro, the then mayor of the Colombian city of Bogotá, said this nearly ten years ago. Bogotá is known for transforming its chaotic roads by making public transport better and sustainable. While the statement has achieved a legendary status and is often cited to make public transport the default mode of mobility in cities around India, the Bogotá template has not really been implemented.

The last decade has seen massive investments in the transport and mobility infrastructure in many cities but not necessarily to improve or expand public transport. The investments have been on big-budget projects such as roads and flyovers which have done little for public transport. As this[1] study in Bengaluru showed, nearly 60 percent of commuters would choose public transit if buses and metro were more available and accessible. This would be true for other cities too that are now increasingly seeing traffic congestion and rising air pollution.

The default approach to improve mobility in cities has been to build more roads; there has been a staggering 73 percent increase in roads from 2016 to 2022 though this includes national highways too and the total budget for this stood at around Rs 1.4 lakh crore during 2022-23, according to official data.[2] More roads have invariably meant more cars. The passenger vehicle sales in India saw 27 percent growth in 2022-23 and is expected to grow at 6-8 percent this year, according to this report.[3] In 2021, Delhi had the highest road length among metropolitan cities, at over 33,000 kilometres;[4] the total number of vehicles registered in Delhi at the end of last year, according to the Statistical Handbook was nearly 14 million[5]

The burgeoning private vehicles in our cities, both motorised two-wheelers and cars, has meant an unprecedented level of congestion on roads, high levels of emissions, longer travel times, and stressed commuters leading to road rage. The rising emissions have contributed to a rise in air pollution levels with the Air Quality Index in many cities touching ‘poor’ or ‘hazardous’ marks. Improving the quality of life and air in our cities requires governments to seriously think on two fronts: one, reducing private transport by facilitating people to use public modes such as bus, trains, even the metro, and two, building the basic infrastructure needed for pedestrians and cyclists. These are essential also for climate action.

The 2011 Census,[6] though old, shows that 36 percent Indians either walk or cycle to work while 30 percent do not travel given their close proximity to their workplaces. Additionally, 18 percent use public transport and 16 percent use private vehicles – 3 percent use cars and 13 percent two-wheelers. While public transport usage may look robust, its share is declining. According to a study by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), the share of public transport is projected to decrease[7] from 75.7 percent in 2000-01 to 44.7 percent in 2030-31.

The shift away shows in investments too. India invests barely 1.7 percent of its GDP in public transport infrastructure and services compared to, say China, which is at 5.5 percent.[8] People’s preference for private vehicles comes from a combination of factors, including their aspirations to own one, but the lack of an efficient, reliable, comfortable and safe multi-modal public transport network is a major contributor too.

Here’s a city-wise distribution of public and private transport modes. Though most show movement away from public to private modes of transport, a few like Bhubaneswar, Bhopal and Bengaluru show the reverse trend too.

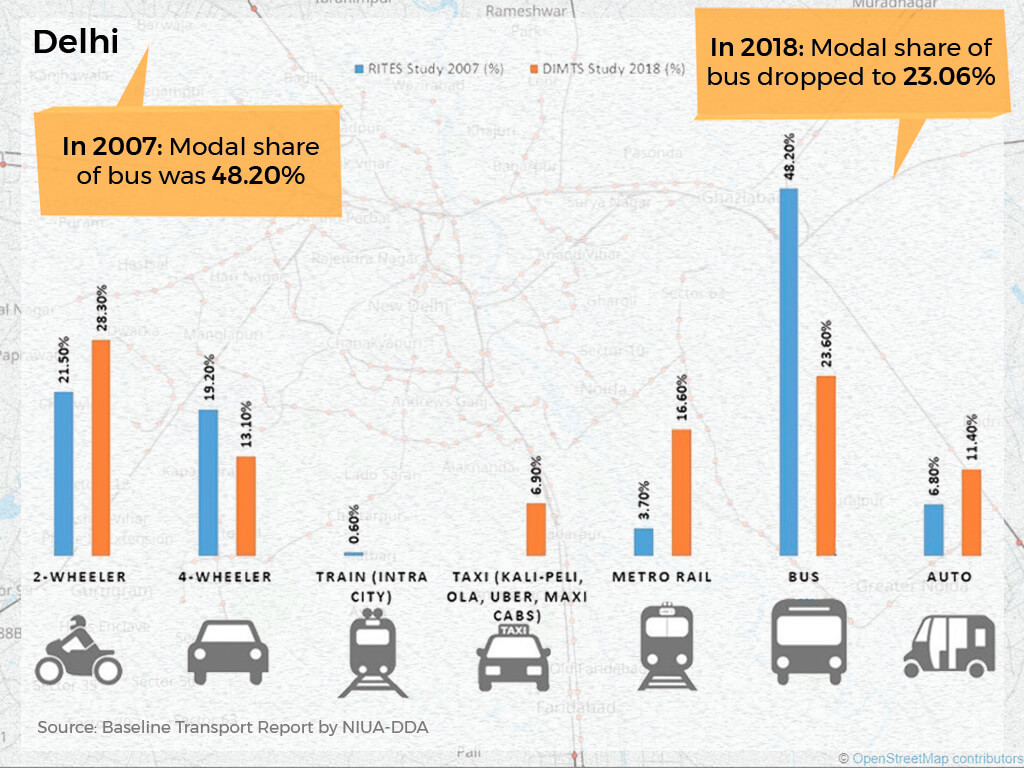

Delhi

The story of Delhi fits perfectly in this shift away from public to private transport. Nearly half its commuters used the bus system, the Delhi Transport Corporation and cluster bus services, in 2007. This dropped to 23 percent by 2018. Some may have shifted to the fast-expanding metro but it scarcely explains the significant drop given that, historically, bus users usually find the metro unaffordable.

The Delhi-NCR has 390 kms of metro lines and a combined fleet of 7,200 buses of the DTC and cluster services.[9] The DTC saw an average daily passenger ridership of 15.62 lakh in 2021-22[10] but the ridership has been declining.[11] Back in 2011, Delhi’s motor vehicle number exceeded that of Chennai, Kolkata, Lucknow and Mumbai.[12]

The Delhi Metro, which started in 2002, has spanned to almost 390 kilometres. While more equitable and climate-friendly than private vehicles, it is inaccessible and/or unaffordable for large sections of working people. Despite the metro, Delhi has seen a modal shift away from public transport. The union Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs stated in a report[13]: “If focus is not given to public transport and non-motorised modes at this stage, then more people will shift to private vehicles, thereby further adding to congestion. The Metro Rail services shall provide some relief in shifting people from private vehicles to public transport. However, it has been seen in the past that due to poor quality of buses/ trams/ non-motorised transport, people have shifted from buses to metro for short trips or opted to continue with their cars and 2-wheelers due to overcrowding on Metro. This trend needs to be reversed by improving bus services, so that car-users may also use the metro comfortably instead of their private vehicles.”

Sustainability in transport, given Delhi’s highly polluted air, is an important factor. A research paper,[14] published in October 2023, stated: “In a city like Delhi, having unplanned urbanisation and unparalleled growth in motorisation, there is a need for increased focus on sustainable use of mass transit systems like metro rails and bus transportation. For transportation to be sustainable, it is equally important to understand the social, economic and environmental sustainability of each of these sub-systems.”

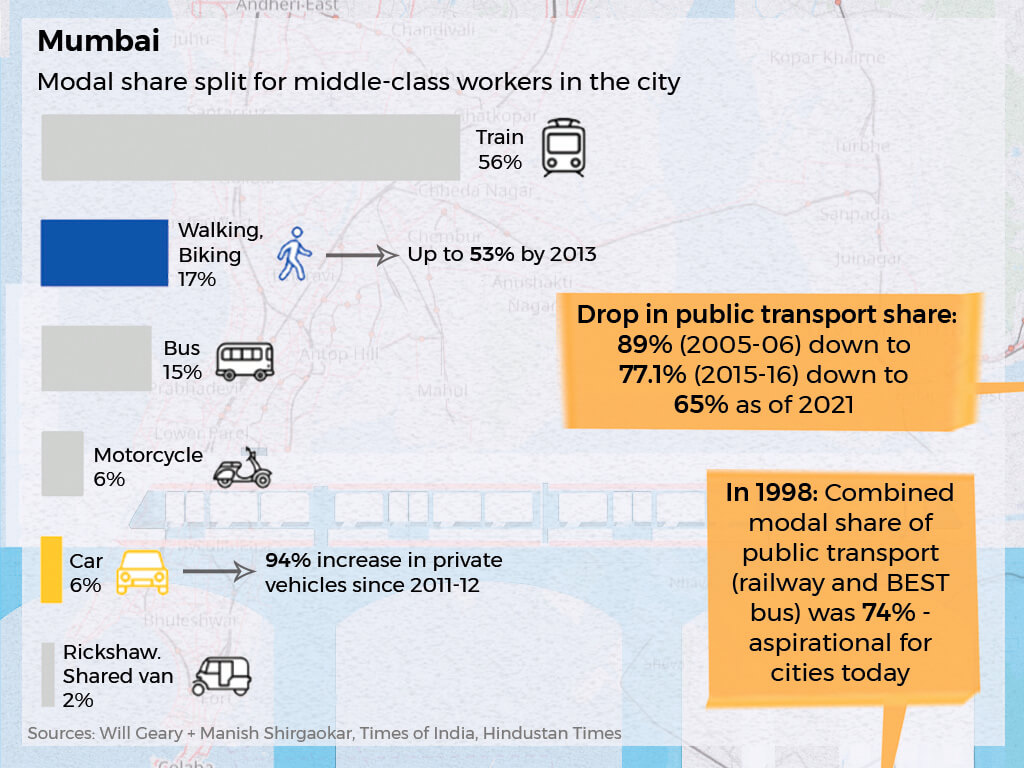

Mumbai

Although Mumbai has more than 18 million people, it has fewer registered motor vehicles than Delhi, Bengaluru and Chennai given that its road length has been near-constant at around 2,200 kilometres. The addition has been through mega projects such as the Coastal Road and Mumbai Trans Harbour Link. Mumbaikars massively depend on its age-old 450-kilometre suburban rail network and local BEST bus system, which cumulatively see ridership of nearly 13 million every day.

However, the modal share of public transport has steadily declined. Based on government data and private statistical agencies, the Mumbai Vikas Samiti report showed that it declined from 89.1 percent in 2005-06 to 77.1 percent of daily passenger trips ten years later.[15] Sociologist and public transport activist Hussain Indorewala showed that the combined share of public transport had declined from 74 percent in 1998 while the share of private transport had increased from 13 percent to 27 percent between 1998 and 2018.[16]

Mumbai has seen an alarming growth in the number of cars and motorised two-wheelers in the last decade with nearly 1.3 million cars and 2.7 million two-wheelers in 2023, according to the state Economic Survey.[17] This is explained as the result of population growth, rising discretionary incomes, and suburbanisation.[18]

Mumbai has prioritised cars. Since 1999, as many as 60 flyovers and several high-speed freeways have been built to “ease congestion” including the Bandra-Worli Sea Link, Eastern Freeway, Jogeshwari-Vikhroli Link Road (JVLR) and Santacruz-Chembur Link Road (SCLR), but the city has no dedicated bus lanes, no regulations against roadside parking on arterial roads, and lacks basic provisions for pedestrians like footpaths and speed limits, showed a report.[19]

While some investment has been made in the railway lines, an independent survey in 2017 showed that 98 percent of the railway stations “pose a high risk or are dangerous” for persons with disabilities, senior citizens, and “lack basic structures such as ramps and escalators”.[20]

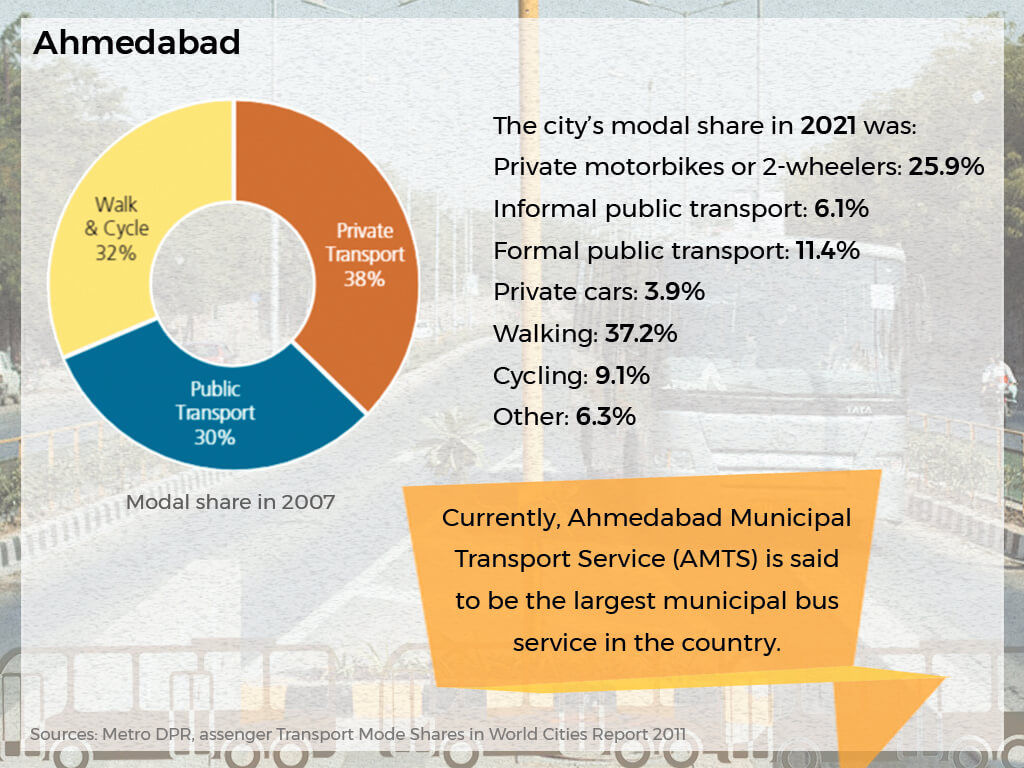

Ahmedabad

With a population of 8 million, Ahmedabad has 55 cars for every 1,000 people. In the last decade, the city got a Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS) and a metro. Ahmedabad Municipal Transport Service (AMTS) is said to be the largest municipal bus service in the country.

Only around 21 percent of people in Ahmedabad use the public transport system with about 0.9 million passengers taking the Ahmedabad Municipal Transport Service buses and 0.15 million using BRTS.[21] Meanwhile, the city has seen a spurt in the ownership and use of private vehicles, especially motorised two-wheelers.

Ahmedabad’s metro started operations in 2022 and it carries 75,000 to 90,000 passengers a day. However, this has not greatly aided the cause of public transport use. The networks together cater to only 6.4 lakh commuters every day – a 22 percent drop compared to the 2009 ridership figures.[22] One of the fastest expanding cities of India has been increasingly relying on private transport modes.

Chennai

The capital city of Tamil Nadu used to preen about its wide bus network with nearly half the city’s commuters using it till recently. However, bus ridership has been falling. The modal split of the 1970-80s which saw only a tiny three percent private vehicle use saw a massive shift in later decades with a near-equal share of 30 percent each in public and private modes by 2010. The train ridership decreased from 12 per cent in 1970 to five per cent in 2008.

“This decline in public transit ridership can be due to the decline in quality of service or the overuse of facilities which has combinedly led to the increase of private vehicle ownership. Non-motorised transport users declined drastically from 42 per cent in 1970 to 28 per cent in 2014,” stated this analysis.[22]

Run by the Chennai Metropolitan Transport Corporation, the bus network is still the most affordable and accessible transport mode for millions in the city. The Zero-Ticket Bus Travel scheme for women, launched in 2021, has contributed to the increase in ridership. The need for public transport has not diminished. India’s first Ease of Moving Index in 2018 found that 75 percent of Chennai’s people prefer public transport with buses as the main mode of transport in the city.

Chennai’s 54-km metro, started in 2015, carries 2.66 lakh a day and shows an increase in passenger count. Over recent years, the city has also seen a rise in motorised two-wheelers. A study by the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) found that Chennai has the highest number of two-wheelers among all metro cities.[23]

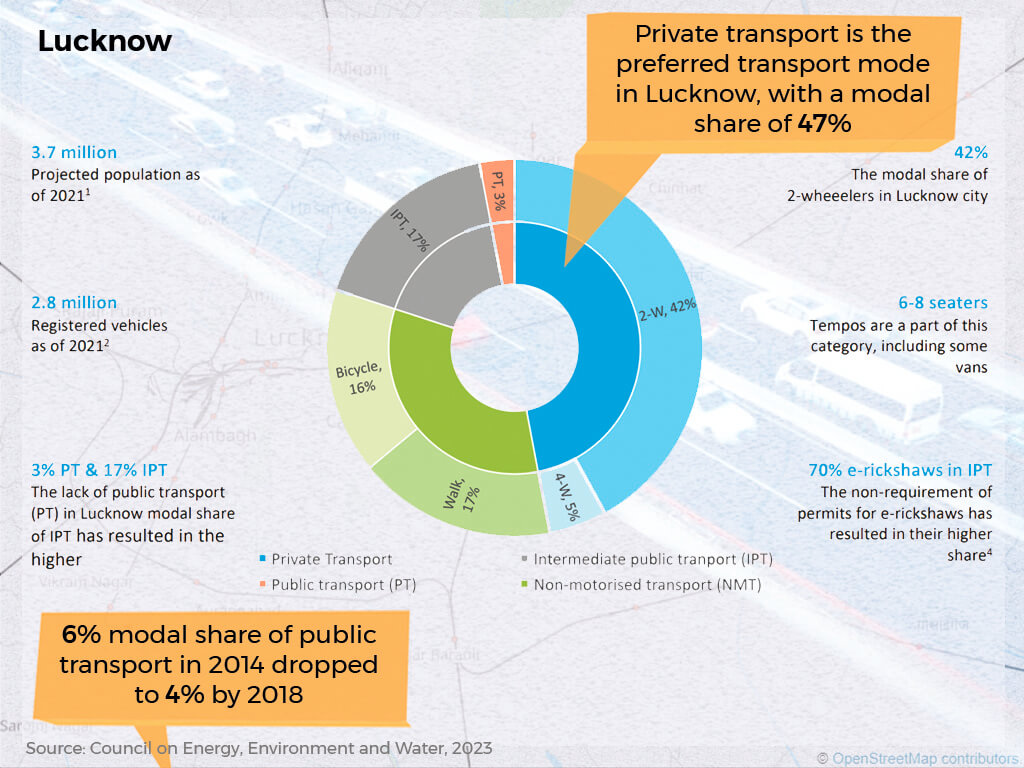

Lucknow

Lucknow is representative of India’s smaller but expanding cities where public transport is sort of insignificant. In 2014, the modal share of public transport in Lucknow was 6 percent while that of two-wheelers was 62.7 percent. Inadequate and ill-maintained public transport options has meant a fall in its usage from an already measly 6 to 4 percent in 2018 while nearly half of all commuter trips are made by private vehicles or intermediate transport options such as tempos.

In the last few years, Lucknow has added more private vehicles on roads and is now second only to Delhi in terms of low vehicle registration cost which encourages people to buy cars adding to the pollution load and worsening parking problems. Public transport continue to be low, hovering around 5-10 percent.[24]

Metro services in the city started in 2017 and, in December 2023, the network had its highest ridership of 22.77 lakhs surpassing the previous highest ridership of 22.08 lakhs in August 2023.[25] The private buses (and a few public ones) auto-rickshaws and vikrams (6-8 seater shared basis taxis) operate on fixed routes.

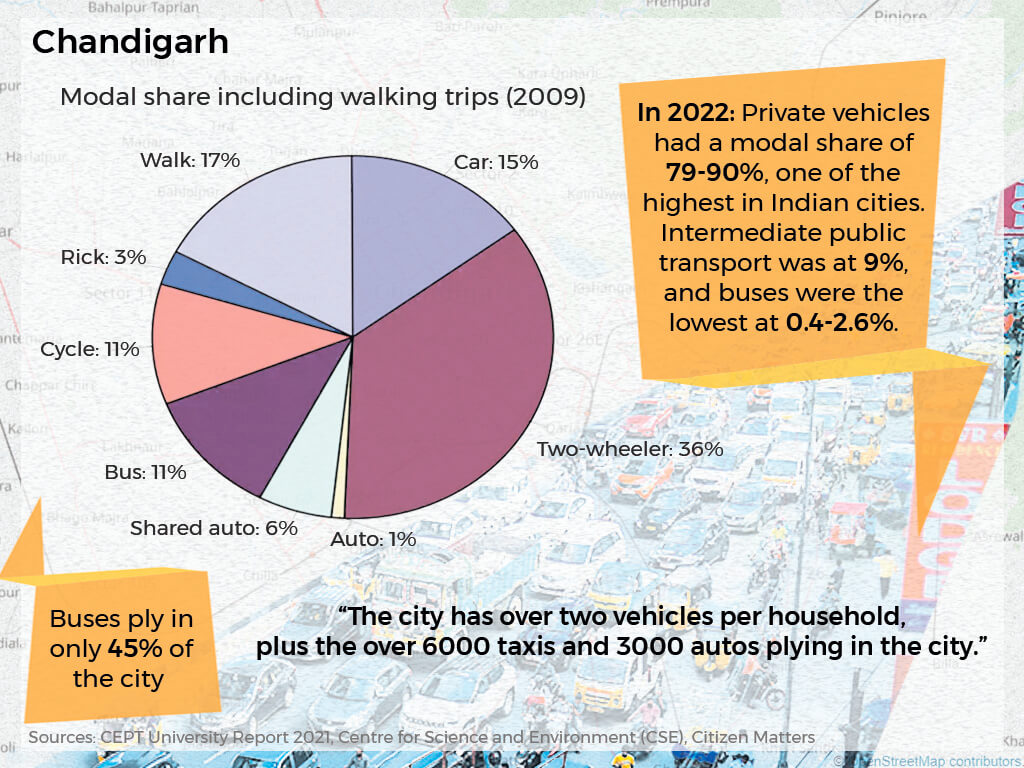

Chandigarh

One of the first planned cities of independent India, Chandigarh is a model for how public transport should not be ignored by planners. Private vehicles have a modal share of 79-90 percent while buses ferry less than one percent and Intermediate Public Transport nine percent of commuters, according to a RITES (Rail India Technical and Economic Services) Report 2022.[26]

A report by CEPT University in 2021 pointed out that only 11 percent of Chandigarh’s population use the bus service and that buses ply in only 45 percent of the city. This forces the growth of private vehicles.[27] In fact, rather than creating infrastructure for public transport, recent concretisation has led to an unfortunate merging of cycling tracks with roads, thus discouraging cyclists.

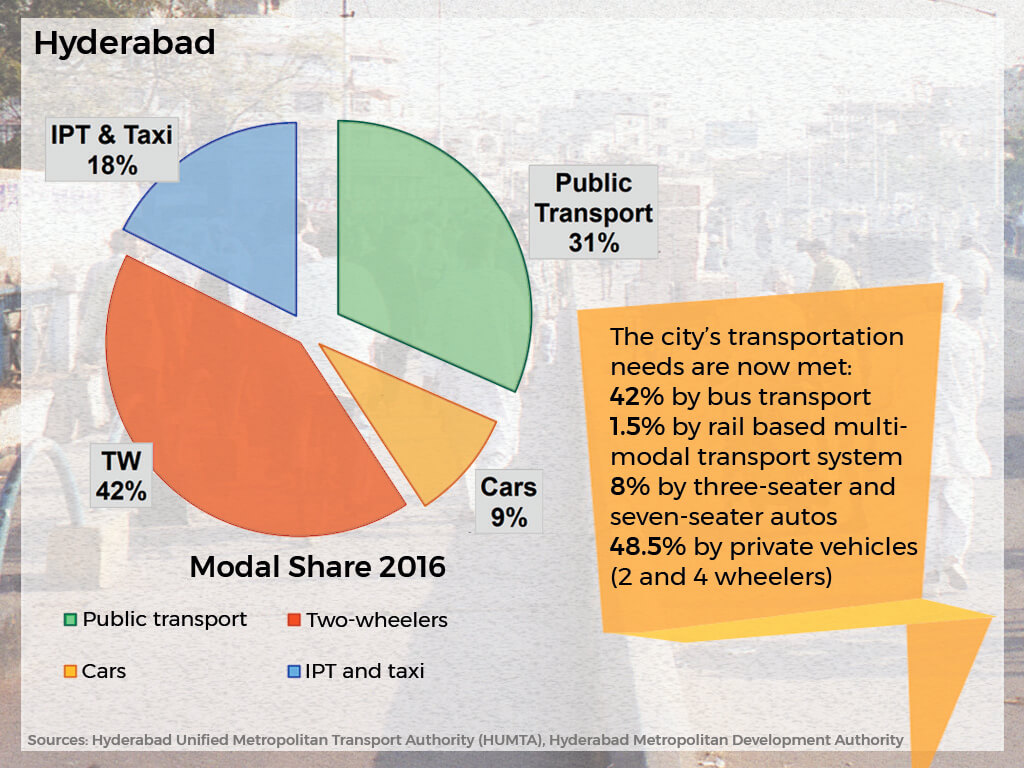

Hyderabad

Hyderabad has seen a drop in the share of buses from 64.3 percent in 1988 to 34.5 percent in 2018 while, in the same period, the modal share of personal vehicles increased from 28.8 percent to 47.8 percent.[28] The city’s transport needs are largely met by bus, three and seven seater autos (8 percent) and private vehicles (2 and 4 wheelers).[29]

After the launch of the free bus scheme last year, the Telangana State Road Transport Corporation (TSRTC) saw a sharp rise in the occupancy ratio. Greater Hyderabad which had an occupancy ratio of 67 percent, now has 87-90 percent occupancy ratio[30] but the network needs improvements, say analysts. The Hyderabad metro, launched in 2017, has seen a steady rise in ridership with the daily number touching nearly 5.47 lakh last September but the proportional percentage is still low.

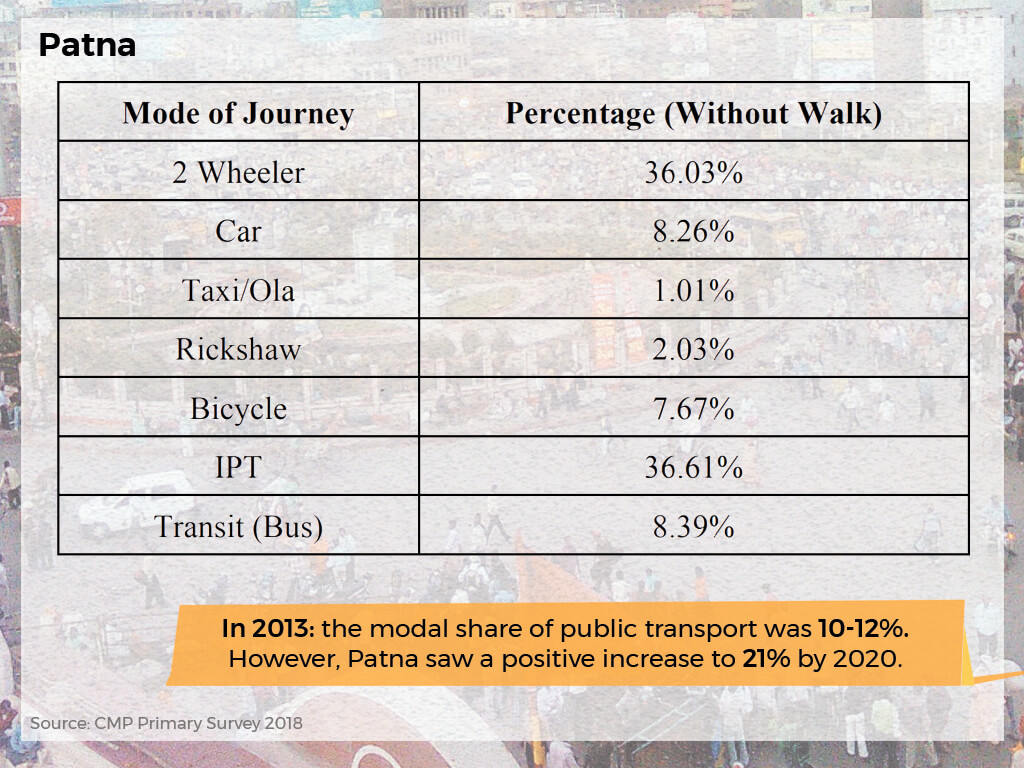

Patna

Bihar’s capital recorded 21 percent modal share of public transport in 2020, a definite increase from 10-12 percent in 2013 but the share of private vehicles (cars and motorised two-wheelers) is still at a staggering 44 percent. Buses form only a small part of the city’s multi-modal network – less than 9 percent.[31]

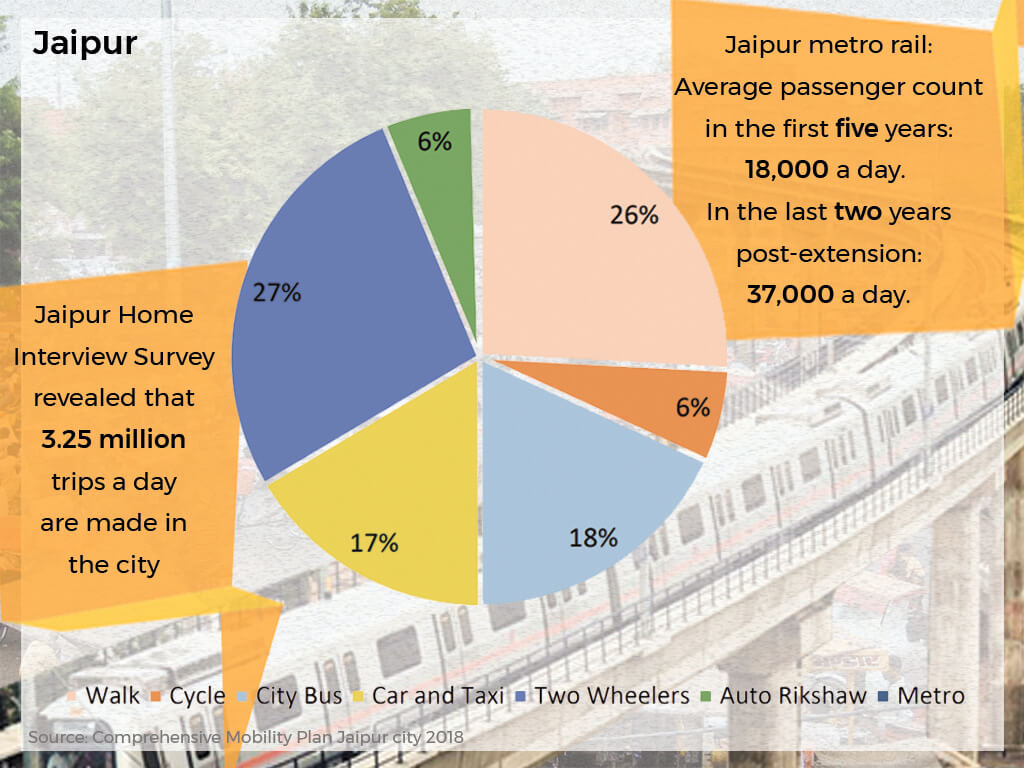

Jaipur

The pink city has autos, buses and eco-friendly CNG rickshaws but residents depend on their private vehicles to travel every day. The bus network, in 2019, catered to about 1.6 million people, about half of the city’s population, while the new metro catered to only about seven percent of commuters.[32]

The bus network, shared between the government and private operators, is not the preferred mode except by those who cannot afford other modes.[33]

The move towards public transport

In the India story of declining share of public transport, a few cities like Bengaluru, Bhubaneswar and Bhopal have shown an upward trend in the use of buses and rail networks. In some, this rise has been driven by the metro. However, experts say that the metro is merely mass transit but not a public transport mode given its selective route mapping and fares which make it unaffordable for the masses.

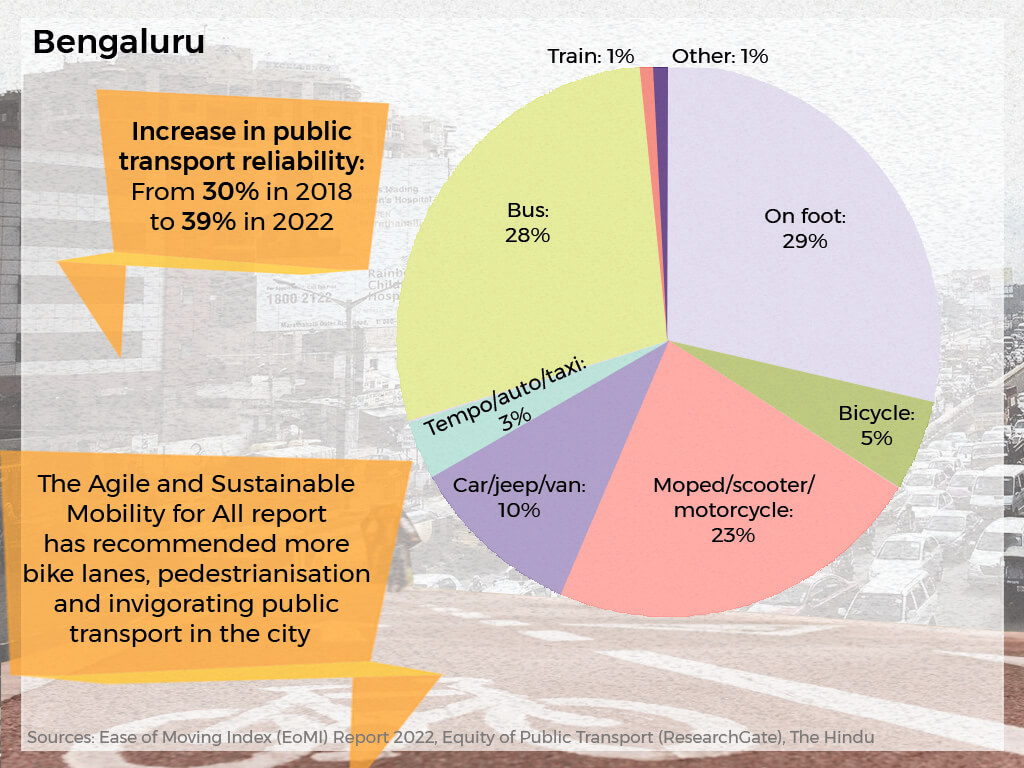

Bengaluru

Bengaluru is both a good and bad news story on transport. While its share of public transport usage has seen a rise in recent years – from 30 to 39 percent, according to the Ease of Moving Index India report 2022 – the numbers of private vehicles has also shown a surge leading to the infamous traffic jams in the city.[34]

In 2023, the Karnataka government introduced Shakti Scheme, free travel for women, which also spiked the public transport users.[35] Nearly 84 percent of households have motor vehicles — about 20 percent have one car and 60 percent of households have at least one scooter or motorcycle.[36] Ashish Verma, mobility expert and convenor of IISc Sustainable Transportation Lab, said, “Metro networks in the core area are required to decongest the traffic. A suburban rail network and robust bus transport are better options to link satellite towns. Building a suburban rail network or making optimal utilisation of the existing rail network with a better integration is (more) cost-effective than building a metro network.”[37]

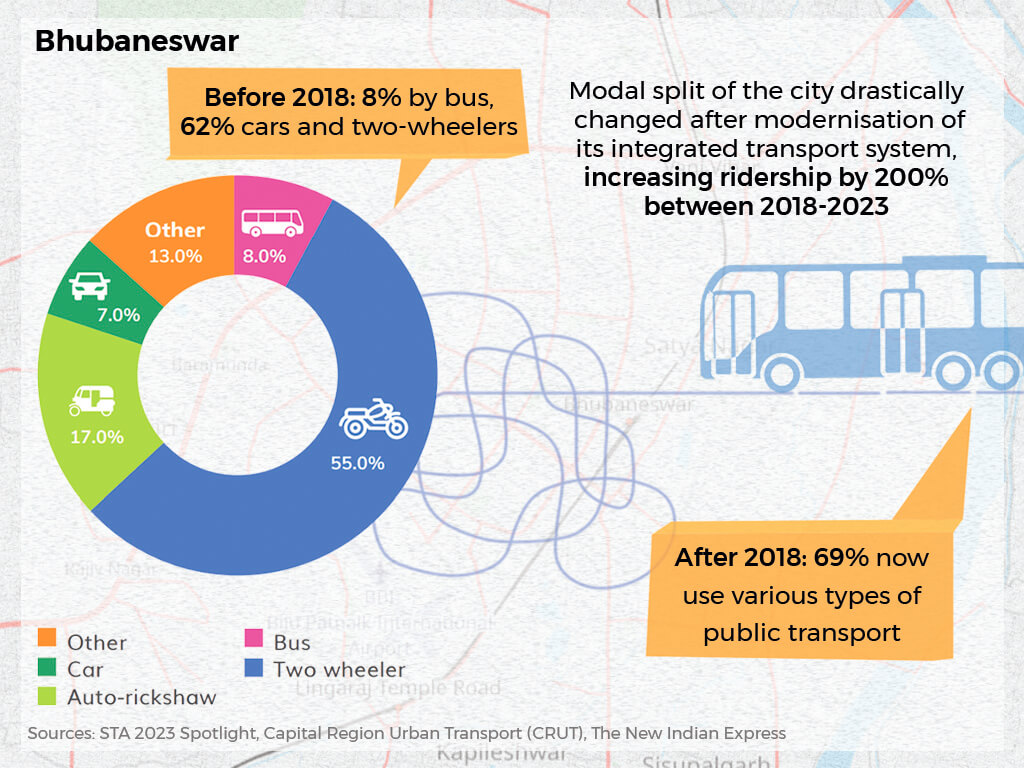

Bhubaneswar

Odisha’s capital and largest city, Bhubaneswar, reorganised the public transport services with the Mo Bus leading the way in 2018. With real-time technology like live tracking, travel planner and e-ticketing in the Mo Bus, and an e-rickshaw system ‘Mo e-Ride’ introduced as a last-mile feeder service to Mo Bus, the modal share of public transport has risen. Around 57 percent use the Mo Bus and its ridership increased by nearly 200 percent in five years. [38]

The system has also turned out to be inclusive and climate-friendly. Nearly 40 percent of Mo Bus conductors are women and 100 percent of Mo E-Ride drivers are women, transgender people, and people from disadvantaged communities.[39] The Mo Bus fleet is electric; coupled with Mo E-Ride, it is estimated to reduce air pollution by 30 to 50 percent. “These electric buses and rickshaws are helping reduce transport-related emissions, improve air quality, lower noise pollution, and enhance the comfort of commuters, further establishing public transport as a more attractive alternative to driving.”[40]

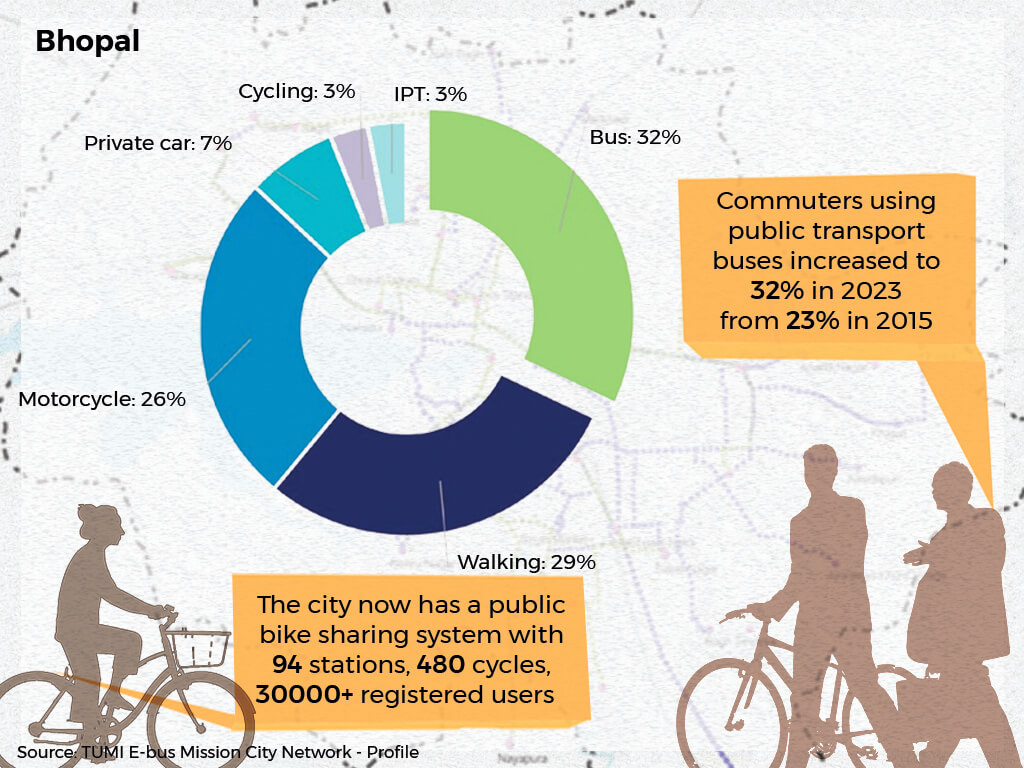

Bhopal

The capital of Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal, has typically a large section of pedestrians with walk trips being nearly 30 percent of all trips. However, the share of bus trips in the multi-modal network has seen a rise too given the augmentation of the fleet of low-floor buses and 40 CNG buses run by Bhopal City Link Limited (BCLL). However, its 24-kilometre Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), inaugurated 10 years ago, is being dismantled due to poor response.

Bhopal’s public bike-sharing system with 94 stations, 480 cycles and more than 30,000 users has made this an attractive and climate-friendly mode for many. The city administration is also on the metro bandwagon but Siddharth Rokade, associate professor at MANIT, says it is “very expensive and time-consuming…the best option remains to strengthen public transport. People see grade separator as a solution, but this solution is temporary. That is why I say that public transport is the best solution to tackle the issue of increasing vehicles”.[41]

It’s a long way and a more concerted effort is needed for India to achieve a robust and integrated public transport system like Bogotá’s.

Shobha Surin, currently based in Bhubaneswar, is a journalist with 20 years of experience in newsrooms in Mumbai. An Associate Editor at Question of Cities, she is concerned about Climate Change and is learning about sustainable development.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.