Mumbai is unimaginable without its robust suburban rail network and well-connected bus system which, together, ferry nearly 12 million commuters a day.[1] From the railway and bus stations, autorickshaws and taxis, plying by meter unlike in most other cities, take commuters to their destinations; many choose to walk too, especially if the distances are short, shopping along the route. Commuters using the existing metro network follow the same model: get off at the metro station and hail a rickshaw or walk to their workplaces, homes and markets.

This idealistic picture makes it appear like seamless connectivity from point to point for commuters. However, it takes one trip by public transport to see the various gaps, uncertainties, and hazards that plague Mumbai’s commuters every day on the proverbial last mile to their homes, workplaces and other destinations. The last-mile connectivity, by motorised vehicles such as rickshaws and taxis or by self-owned two-wheelers or walking, presents untold daily challenges to millions, often causing delays or putting them in harm’s way as they jostle for space.

The last-mile connectivity is commonly understood in urban planning and design as the connectivity of a main transport network to its ancillary networks which take people to their destinations from transport hubs, or simply the last leg of your commute. Its flipside is the first-mile problem which means commuters face issues reaching transportation hubs; this is less of an issue in Mumbai though the mode of walking has the usual challenges.

The last-mile connectivity can make all the difference between a time-bound comfortable commute and a delayed frazzled one. Taxis and rickshaws randomly turn down rides, they may not be available outside railway and bus stations during demand surge or not take passengers in queues, bus routes that serve as feeder routes from the railway and metro stations have long snaking queues, and walking in Mumbai – except a handful of high-end locations – is like a hurdle race where people have to fight for space on footpaths that exist or simply face hazardous traffic where they do not.

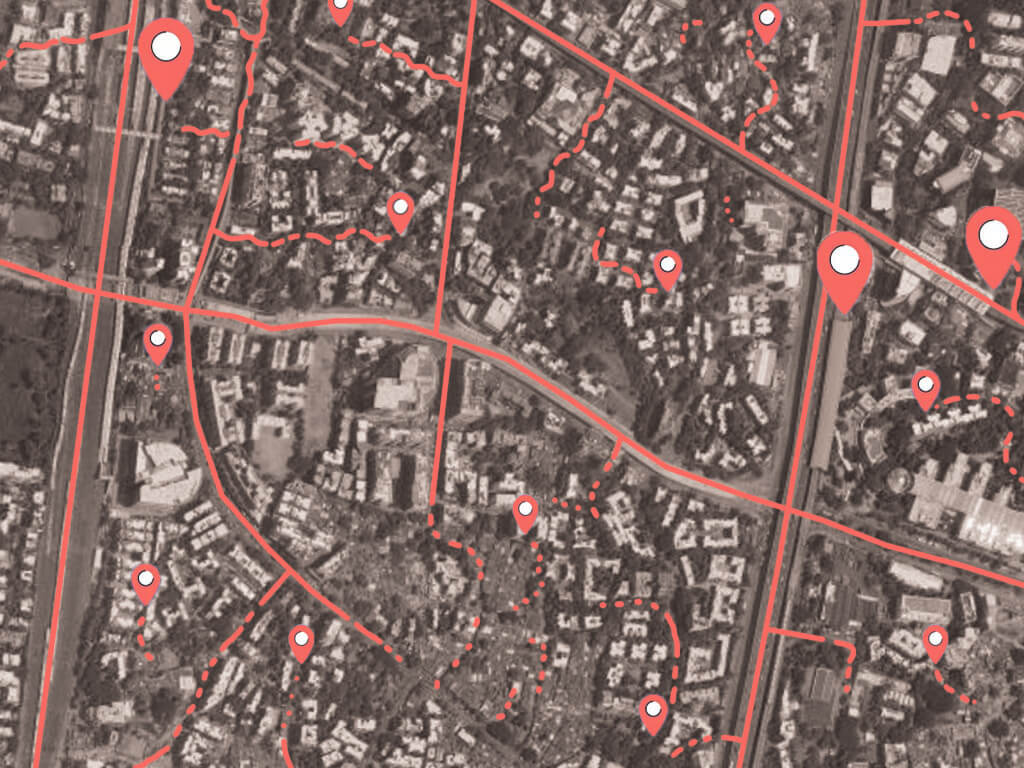

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The last mile can, thus, add endless minutes to an already long tiring commute. For instance, it takes anywhere from 30 to 45 minutes by bus to reach the software and commercial hub SEEPZ from Andheri station, about five kilometres away – more than the time taken to do the north-south 28-kilometre Andheri to Churchgate by train. Also, the lack of last-mile connectivity brings in uncertainty – some days may turn out to be lucky and others, terrible, especially in the monsoon when there is a heavy downpour.

Despite its critical importance to the daily commute of millions, the last-mile connectivity has not been a major deliberative issue on the agenda of transport planners and policy makers, and hardly receives attention in the mainstream media. This is exacerbated by two factors. One, the large spaces used as holding areas for two-wheeler parking and rickshaw stands outside the suburban railway stations have been steadily shrinking over the years, pushing these users onto the streets which usually creates massive logjams every morning and evening.

Two, the spaces outside the main transport modes such as the railways, metro and long-distance buses have been designed and built more for private vehicles which want clear roads to whizz by; there are virtually no holding areas outside even the newly-constructed metro stations with several bridges dropping off commuters on arterial roads and highways. The odd rickshaw or taxi parked at these points play hard to run the last-mile ride to destinations that people request. The last-mile connectivity matters a great deal in Mumbai because nearly 65 percent of the city’s population uses public transport and depends on the last-mile connectors to reach their destinations.[2]

Increasingly, BEST buses are being turned into feeder routes from railway stations but it has not helped last-mile connectivity. The network’s reduced fleet and out-sourcing to private contractors have meant longer wait times, smaller buses, overcrowding and a general drop in quality[3] The average speed of buses dropped from 16 to 9 kilometres per hour between 2008 and 2018 too.[4]

This coupled with the lack of regulation of rickshaws and taxis, and the non-provision of space at metro station or footpaths has considerably added to the average commute time for most Mumbaikars. On an average, this can be an astounding 2:20 hours a day leading to frustration and exhaustion.[5]

To map the shortcomings and challenges of the last-mile connectivity, a team of QoC reporter-writers teamed up with Walking Project’s representative and journeyed to a handful of locations, including the city’s new-fangled corporate hub Bandra Kurla Complex.

Each location we chose had its own set of problems. Shining a light on them at the granular level, we hope, will get the authorities moving to fix the all-important last-mile connectivity.

Photo: Vedant Mhatre

Bandra Kurla Complex

Developed from the marshes, the Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) is Mumbai’s hottest address for corporate headquarters and high-end residential complexes. The area lies to the east of Bandra railway station and to the west of Kurla railway station. BKC has also emerged as a sought-after cultural and entertainment destination. All this means that people flow to and from BKC is varied but last through the day and night.

From Bandra East, it could take anywhere from 11 minutes to 25 minutes to reach parts of the sprawling area. At the foot of the railway overbridge in Bandra east, where Anant Kanetkar Marg starts, rickshaws scream, soliciting commuters: “Diamond BKC! One BKC! BKC! BKC One! BKC!” There is an apology for a bus stop, a short distance away with routes terminating in BKC. A rickshaw ride will typically take 10-20 minutes and cost Rs 30 to Rs 50. Buses leave every few minutes and a ride costs Rs 6. Getting to the bus stop requires considerable deft manoeuvres through the thronging rickshaws. The dust is suffocating, noise is deafening, and the stench overpowering it all.

There used to be a skywalk here, more than a kilometre long, connecting Bandra station with BKC. Though built with great flourish for pedestrians at Rs 14 crore,[6] it was taken down to facilitate flyovers to the BKC in the last few years. Walking to BKC takes 35 minutes on a good non-rainy day but it means negotiating roads and traffic given the lack of footpaths on the Kanetkar Marg till the main crossing at the Western Express Highway, after which footpaths as broad as a road skirt around buildings of the BKC.

The investment in and attention to footpaths could not be more stark in the less well-off parts near the station and in upmarket BKC. The difference in walkability is like night and day. On the Kanetkar Marg, shops and locals spill onto the street, cooking and washing are done on the streetside, hawkers vie for space, footpaths are disjointed and uneven, and heaps of garbage are common. Imagine walking to and from work here every day. In BKC, footpaths are a dream to walk on.

Getting to BKC by bus, we found, was cost-effective at Rs 6 for an air-conditioned bus ticket but it was exhausting to wait in the harsh sun and humidity next to the stench from the Mithi river. We first walked some distance from the station to the MMRDA bus stop and then boarded the 310 AC double-decker to Diamond Market on BMC Road. It took us 12 minutes from Bharat Nagar bus stop to Diamond Market bus stop on the mainroad outside BKC, it would take as much or more time during the evening peak hours.

During the walk across the old Kalanagar area, the tactile guidelines meant for guiding the visually impaired were within inches of obstacles; the overhanging branches of trees hanging low could injure even the able-bodied.

While BKC may have state-of-the-art infrastructure within the precinct, it is still a difficult destination to reach for the lakhs who use public transport to reach their workplaces here; only the car users have it smooth.

Our team also mapped the last-mile connectivity from Kurla. Central BKC is approximately 2.5 kilometres from Kurla station along the arterial Lal Bahadur Shastri Marg that’s always congested and without adequate footpaths. The gleaming towers of the BKC are visible across the Mithi river from here. A walk across the Mithi’s banks could cut the journey from 25 to 15 minutes. The relatively new BKC-Chunabhatti connector flyover can speed up the last-mile connectivity but it is barred for two-wheelers and no space has been provided for pedestrians – as always uncounted in road design.

Leaving BKC during the evening rush hour is like fighting against the tide – one bus after another whizzes past filled tightly like a sardine can, rickshaws merrily refuse or charge non-metered rates which the authorities do not regulate, walking is a challenge given the lack of adequate infrastructure. From 5pm to 7pm, there are ‘ladies special’ buses from BKC to Bandra station every 15 minutes but they do not stop at all bus stops and have no signage to indicate to women commuters.

From designated stops across BKC, share rickshaws charge Rs 30 per seat, making a cool Rs 90- Rs 100 for a ride that should cost Rs 36 only. Rickshaws plying long distances to Juhu, Andheri, and Borivali in Mumbai’s western suburbs and Kurla, Ghatkopar, Mulund in the central suburbs, quote exorbitantly high flat rates, refusing to go by the meter. The Regional Transport Office and Mumbai’s Traffic Police cannot be unaware of this brazen flouting of regulations which place a burden on money and time on harried commuters; there has been no lasting or visible crackdown.

After office hours, BKC commute becomes harder as the area becomes deserted, unlike a mixed-use area, and rickshaws take advantage of this. The number of buses whittle down too and the wait for a bus can seem quite lonely or hazardous especially for women, at the unshaded stops. Tired and want to sit? There is no street furniture here. Restaurants and coffee shops are exorbitantly priced, squeezing out options for the low-end executives and the working class.

The last-mile connectivity to BKC, from Bandra and Kurla, can be quite nightmarish. It is a haven for those commuting in private cars, though.

Wadala to housing colonies

Wadala Road station on the Harbour Line of the Central Railway caters to the eastern neighbourhoods along Mumbai’s natural harbour. Once a truck terminal and site of industrial estates interspersed with bungalows, Wadala is now the gateway to a stream of highrises that are somewhat incongruently called “Upper Cuffe Parade” to suggest south Mumbai sophistication, not suburbanism. Wadala is also the railhead for large lower-middle class and government employee colonies in Antop Hill, Pratiksha Nagar which has a major bus depot, and on the east, the massive settlement of Sangam Nagar. Lakhs of people going to work and returning home would be beset by issues of the last-mile connectivity from the station.

The station’s two entry-exits after two flights of stairs are narrow. Opening out to main roads, the last-mile connectivity in Wadala west and east differs; the latter, as it usually is, shows neglect and lack of planning. The exit here leads you on to an 800-metre skywalk – a pedestrian walkway above a busy road but often occupied by hawkers and homeless people. The entire stretch was lined with trash of various kinds including red paan stains that have become synonymous with boundary walls.

The skywalk is undignified to use during the day given its commuter-unfriendly design and poor maintenance. We stepped on broken tiles, skirted around hawkers and waited for people to pass, as we looked for any signage that could help us orient ourselves – but none were present. We were also blinded by the grey metal sheets that separate the skywalk from the buildings along it. We ultimately resorted to using Google Maps but still found it difficult to orient ourselves.

Though it was a pleasant winter afternoon, we felt claustrophobic on the skywalk. There were hardly any sections with sides open to view, allowing air in and giving us visibility. It dropped us near the dilapidated Bombay Port Trust housing colony’s ground which felt like an oasis. We stood reflecting on the state of the skywalk and felt relatively fresh air wash over us. It was a good Air Quality Index Day for Mumbai, averaging around 75 and underscored, once again, the importance of public transport in reducing emissions.[7]

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

At the exit of the skywalk were whimsically parked two-wheelers and incessant honking, but no footpath. The nearby intersection of three main roads meant pedestrians risked their lives and limbs to cross it in order to reach the station or the skywalk. Parents accompany children on the way to school and classes; walking here is so fraught with risks that even older children are not by themselves.

Somewhere tucked away opposite the exit are two small bus stops that are barely visible. Buses can take you from Wadala East all the way to Colaba in the south, but their frequency is low. An 18 year-old student waiting at this bus stop to go to college in Bhoiwada, Parel, usually has a wait time between 10-20 minutes. She says she can take a train to Sewri, but her only option to reach college is by foot, as no cabs agree to that distance and it is relatively more expensive.

From the residential areas identified, there are buses at 3-minute frequency to and from the station but the bus stops hardly inspire confidence. They do not even have standardised signage, they were covered with banners of political parties, and offered inadequate space for commuters waiting for the bus. Invariably, they were pushed to wait on the road risking their lives and obstructing vehicular movement.

The west exit has a different story. Leading to Five Gardens in Dadar, Kidwai Nagar, and the famed engineering institute VJTI, the last-mile connectivity is a few shades better. It also boasts narrow exits but opens on to a busy and wide road which has designated spots for buses, a short walk to the monorail station going towards Lower Parel and Chembur, rickshaw and taxi queues. The footpaths here can be called semi-walkable though hosting the ubiquitous hawkers and even a police van. This part, leading to Dadar offers commuters the basic last-mile connectivity options such as taxis and buses, and space to navigate in and out of the station – basic but more pleasant than in the east.

In Wadala west, commuters are connected by BEST buses, cabs and the monorail. Commuters from east often have to take the bus from wherever they live in Pratiksha Nagar, Antop Hill to the west side of the station or walk the long and dirty skywalk after taking the bus till a point in the east.

Wadala is quite central in Mumbai but the last-mile connectivity from the station to nearby destinations is rather poor.

Vile Parle to Juhu

Between three and four lakh commuters use Vile Parle railway station daily.[8] The west side of the station leads to the upmarket housing area of Juhu, where a number of film stars live, and to nearly a dozen colleges and other educational institutions.

The station is teeming with students, naturally. Through the day, as rickshaws accept or refuse rides to colleges, charge Rs 20 per student in a share rickshaw earning a total of Rs 60 or 80 for a ride that costs half of that, so students are forced to walk. But footpaths are either absent or broken or occupied perpetually by vegetable and fruit vendors, stalls selling clothes and footwear, and streetside food.

The skywalk from the station to the main Swami Vivekanand Road is replete with the problems that all skywalks show – mounds of garbage piled up, broken tiles and uneven flooring, random addicts and homeless sprawled, and here even a generator right in the path of pedestrians. The roads leading to the station are narrow and winding, fit only for two-wheelers and a car, but see large vehicles round the clock. There are no designated bus routes from the station to the college areas of Juhu – a glaring miss not set right after all these decades. The nearest bus stop, at Ashoka Hall, requires one to walk till the main road where route 339 takes twice as long as a rickshaw ride, taking a long and circuitous route.

In the design of the skywalk, in the approach to the railway station, at the traffic intersection that sees thousands of young students crossing every minute, the pedestrians do not seem to be accounted for. Walking to colleges like Mithibai and Narsee Monjee (NM) should take about 15 minutes but takes longer due to the obstacles along the route; walking deeper into Juhu is no less challenging except that the footpaths are wider and have fewer obstructions as the sections with well-to-do people and films stars start.

The class divide, so apparent in Mumbai’s life, is evident in the last-mile connectivity too, especially in the Vile Parle-Juhu stretch.

However, Mumbai has a template in building seamless last-mile connectivity. Decades ago, when Nariman Point and Cuffe Parade precincts were developed as the central business districts to rival the old Fort-Fountain area, share taxis and round-the-clock buses were allocated to holding areas near the rail hubs of Churchgate and then Victoria Terminus.

Even today, you can alight from your train journey, long or short, at these stations and within a few paces find either the taxi stands or bus stops to take you to the business districts. Walking is a pleasant option too if you do not mind the rather long distances; a walk from Churchgate to Nariman Point, on wide (nearly 7-8 metres or as wide as some streets in the suburbs) and unobstructed footpaths, also take you by the sea – the ultimate Mumbai experience.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. A recipient of the Laadli Media Award 2023, she observes and chronicles the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic.

Vedant Mhatre, activist with the Walking Project, passionately explores the complexities of the modern urban landscape, focusing on urbanism, transportation, and climate issues. Adept at crafting online campaigns to drive attention to urban challenges, he creates and uses informative videos on these topics to drive home the point. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Electronics Engineering.

Shivani Dave is an architect, writer and illustrator interested in exploring the intersection of architecture and social sciences. After graduating in architecture from Mumbai, and in media from the London School of Journalism, she is applying the fundamentals of architectural research and writing within urban contexts to develop phenomenological ideas about life in cities. She researches, writes and illustrates in Question of Cities.

Cover illustration: Shivani Dave