In Mumbai’s Dadar, a kilometre’s walk from one of the busiest suburban railway stations is the Dadar Parsi Colony. Wide roads with spacious footpaths are lined with trees, both native and exotic – Banyan, Almond, Copper pod, Trumpet, and Hatiamiuki to name a few. Mumbai’s noise, pollution and heat fade out here. Even in Mumbai’s infamous October heat, the drop in temperature is perceptible and bird calls are crystal clear.

Among Dadar Parsi Colony’s long-time residents is children’s author Katie Bagli, who has recorded the 60 types spread across 25 acres[1] in a book called Trees of Dadar Parsi Colony. The colony was an effort of the Bombay City Improvement Trust in the early 20th century to provide Parsis with a tree-lined precinct and civic amenities. “Besides the Five Gardens, this area has 14 smaller gardens and trees lining each avenue,” says Bagli. She is also a trustee of the Save Rani Bagh Botanical Garden Foundation, another conserved spot of green near the zoo.

Scattered among its concrete and glass facades, Mumbai is home to a few green pockets such as the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Aarey forest, mangrove forests and wetlands along its coastline, swathes of green concentrated in a few pincodes. Dadar Parsi Colony is one where trees and buildings appear in harmony rather than conflict – an exception or an oasis in the city where trees are being overrun by construction.

Illustration: Shivani Dave

Plants of the Parsi Colony

The quiet and shaded environs of the Dadar Parsi Colony do not seem to be a part of the frenetic and noisy Mumbai, thanks to its widespread canopy of common and exotic trees. The greens form the nucleus around which the colony stands, forming a natural barrier between it and the city beyond, absorbing and filtering the city’s noise and fumes. If this could be planned and executed back in the 1900s, why couldn’t more areas of Mumbai be built this way?

Bagli, a naturalist and tree lover, identifies shapes, sizes, colours and contours of their leaves, flowers and trunks. And she is delighted to walk around with me. Five Gardens is an amalgam of one central circular garden and four around it, all separated by tree-lined roads with residential buildings. We begin walking in Garden A and she shows me the Wild Bhendi tree and its fruit with fluorescent yellow flesh underneath brown skin. We move to the Rusty Shield Bearer to see its rust-coloured pods.

Around us are indigenous and easy-to-spot species like the Banyan, Peepal, Indian Rubber, and Indian Almond among others. There are exotic ones like the umbrella tree and the Copper Pod whose flowers form a bright yellow carpet on the ground, attracting pollinator birds like bulbuls and parakeets to them. We then spot the Trumpet Tree, a cousin of the world-famous Cherry Blossom.

“They look gorgeous when they are in bloom on the Vikhroli stretch of the Eastern Express Highway,” Bagli says. I remember that visual relief. We come to the road that runs between Gardens A and B which hosts two of the six Hatiamiuki trees; the other four are scattered around the colony. “Their gnarled trunk signifies that they are at least a hundred years old,” says Bagli. We cross the road to see the Putranjeva, whose little round seeds are made into necklaces only for boys. “People build myths around trees. No one’s going to harm their sons, so the tree lives on.” The patriarchal belief may have protected this tree.

Spotting a Rain Tree at the centre of Garden B, Bagli bursts into child-like giggles and explains that its leaves droop in the evening which leads to insect droppings that feel like “rain”. Nearby, an Indian Almond tree stands with its leaves turning red, preparing to shed, its neatly-tiered branches a distinguishing characteristic, and its soft and fibrous fruit enjoyed by birds.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

The riches within

A little ahead, the Tiwar tree stands out. According to Bagli, this is not only because of its tiny pink flowers with striking red stamens but also because of its cylindrical shaped fruits with edges at acute angles. I also learn that the leaves of the Indian Rubber tree have a red sheath before they fully open, and this tree is usually mistaken for the Banyan because of its hanging roots. A butterfly nestles among the Bottlebrush shrubs before flying away. In how many areas of Mumbai can one do this?

Bagli points to moss-covered stones around the Peepal, explaining that while the wind and water erode rocks, the moss secretes a substance which breaks them down into soil over time. The wonders of nature do not cease. Then, there’s the Star Apple tree whose copper undersides shine like gold in sunlight; the fruits of the Guest Trees are fondly called ‘jewel boxes’ or ‘pearl capsules’ with their white seeds resembling pearls.

Trees, even in the harsh and polluted atmosphere of the city, hold entire worlds within themselves; their ecosystems nurturing life processes of insects, bats and birds, their flowers and fruits serving as food source, their soil binding organisms underground, their fallen leaves and flowers decomposing into soil, and their shade cooling busy city people. Sustain trees and they sustain you, your city and your world.

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Further along the Gardens, the Wild Almond or Jungli Badam is a busy tree with the dull white and small shell-like protrusions on its bark; Bagli points out that these are moth cocoons. We pick up a fallen fruit with a woody exterior only to see white ants engrossed in decomposing it; Bagli carefully replaces it so that the ants are not disturbed.

Under the shade of the Shirish tree, people rest oblivious that its rattling pods are called ‘woman’s tongue’. Students choreograph dances under the Rain tree, a man sleeps in the shade of Wild Bhendi and two women sit a short distance away glued to their phone screens, a man eats his lunch under the Banyan, fruit vendors use the shade of trees for their businesses, and lovers of all ages find space on benches under the trees here. The trees also provide refuge to rare birds like hornbills, cattle egrets and night herrings, who Bagli informs, prey on the snakes in the nearby Sewri salt pans.

Take away the trees and Dadar Parsi Colony will simply not be the same. It stands out as an example, even today, of how trees – natural ecology – can nourish and support neighbourhoods. It also exemplifies the planning principle rarely followed – cities can be built along tree-lined avenues and neighbourhoods around gardens.

Photo: Suditi Gupta

Green beyond the colony

The Five Gardens is a green oasis now intruded by vehicles and the occasional high-rises. The buildings encircling the gardens were planned as three-floor structures with balconies facing the neighbourhood or inner streets and gardens; each plot also had a garden of its own. Bagli recounts when she used to taste the nectar of Oleander flowers in her grandmother’s garden here.

The redevelopment bug has crept in here too. “The newly redeveloped buildings don’t have gardens or common open spaces,” Bagli says, adding that the concrete allows no trees and their ecosystems to grow. These buildings have concrete walkways devoid of trees, manicured terraces rather than trees in their compounds. With resignation, she adds, “We cannot stop change but we can save what’s left of the trees.”

Urbanisation is not the only woe for the trees. They are subjected to fairy lights wrapped around their trunks which disturbs the bats and birds. Besides, Climate Change has made the flowering patterns of these trees erratic; the Amaltas trees which used to flower in spring-summer are seen flowering in October too.

Legend has it that Mumbai’s coconut palms were introduced to the old Mahim island by Raja Bhimdev in the 13th century.[2] and Mazgaon island, in south Mumbai, was famous for its mango orchards. The mangoes were apparently sent to the Mughal rulers, and are mentioned as the ‘mangoes of Mazagong’ in the poem Lalla Rookh by Thoma Moore, written as far back as 1817.[3]

Many of Mumbai’s localities were named after the trees and flowers found in local groves long before the islands were engineered into a city. Worli is named after its Banyan grove, Parel derives its name from Trumpet flowers called Padel by the native Kolis. Chinchpokli, which was earlier called Chinchpooghly, means a dell of tamarinds (chinch is tamarind in Marathi and Konkani). The Bhendi tree lent its name to Bhendi Bazaar while the jackfruit known as Fanas gave the name Fanaswadi to an area in Kalbadevi. Umarkhadi gets its name from being the khadi or creek where umber or fig grew.[4]

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

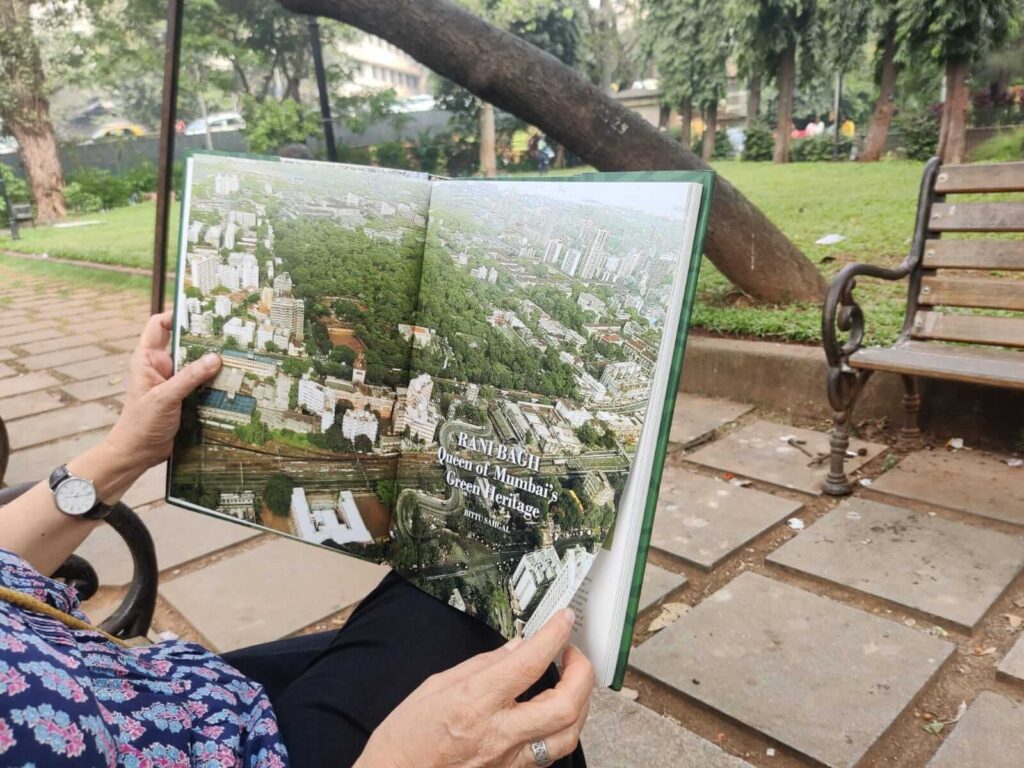

According to a study by Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Mumbai has 318 species of trees, of which 50 percent are exotic, but this is a somewhat older chronicle of the city’s flora.[5] The Sanjay Gandhi National Park, Aarey forest, Veermata Jijabai Bhosale Vanaspati Udyan, Hanging Garden, Mumbai Port Trust Garden and of course, its mangroves are the other green spots. The word ‘Vanaspati’, meaning ‘botanical’ was added to the garden’s name in December 2022, to emphasise its importance as a heritage botanical garden, thanks to the sustained effort of the Save Rani Bagh Botanical Garden Foundation of which Bagli is a trustee. It managed to save the garden from being turned into a “world class zoo” and hold it as a green heritage.[6]

Hutokshi Rustomfram and Shubhada Nikharge, trustees of the Foundation, supervise the renovation of the Bagh. “Given Mumbai’s high population density and poor air quality, the Rani Bagh garden sprawling 60 acres is literally a life-saving green lung, and footfalls prove that Mumbai’s citizens love and value this space,” Rustomfram says. With an average of 8,000 visitors a day, going up to nearly 30,000 on holidays, the Rani Bagh could well be one of the most visited botanical gardens worldwide, she adds. It has “the largest agglomeration of 4,131 trees across 256 species, and holds 80 percent of all tree species found in Mumbai,” Nikharge says.

The century-old Sundari, or the Looking Glass Mangrove of Maharashtra, is found here. It is native to the Sundarbans. The Krishna Fig or Krishna’s Buttercup is a one of a kind tree that is said to be found only in Rani Bagh. The Mumbai Sugran, which is endemic to the island of Mumbai, and is not found in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park is found here and is known as the Rani Bagh Sugran. It is the only surviving member of its species.[7]

Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

Up north, in the Aarey forest, the Waghoba Habitat Foundation has been conducting foraging walks led by the tribals or adivasis of Aarey. Sanjiv Valsan, founder of the Waghoba Habitat Foundation, believes that the Uddhav Thackeray- government’s decision to declare nearly 800 acres as forest saved the trees here. The walks have generated curiosity amongst people and rekindled a sense of pride among the adivasis of their culture. “In a time of climate anxiety, the walks provide an alternative way of being with trees, the way that the adivasis have done from time immemorial,” he says.

The forest has at least 86 species of trees, found a study by activists in 2019, including the Babul, Palash, Bartondi, Apta, and Karvat to name a few. Among the trees recognised by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are trees like the Teak, Indian Beech and Golden Shower to Red Silk Cotton, and exotic species such as the Rat Poison and Jujube trees. The Aarey forest is also a part of Mithi River’s floodplain.[8]

Mangroves and more

Mumbai is also endowed with mangrove forests along its coast. Mangroves act as barriers against floods, storm surges, tidal waves and also tsunamis while also protecting the coast from erosion. Warming seas have meant that the Arabian Sea, which rarely ever sees cyclones, saw Cyclones Nisarga in 2020, Tauktae in 2021 and Biparjoy in 2023. Mumbai lost 9,000 acres of mangrove cover between 1991 and 2001 but has since stabilised after citizens’ movements and judicial interventions.[9]

Mumbai’s Trans Harbour Link, the Coastal Road Project, the Mumbai-Ahmedabad Bullet Train Project and even the Navi Mumbai Airport are some of the infrastructure projects that threaten the mangrove cover even today.

The lingering smog and heat in Mumbai underscore the need for trees which act as barriers against pollutants, ‘removing’ them from the air, and physically collecting particulate matter on their leaves and barks.[10] They dim out the high decibel noise of city life, as we experienced in Dadar Parsi Colony and Rani Bagh Botanical Garden. Mumbai needs more areas like these. The Dadar Parsi Colony is a testament to the planners of yesteryears. Its tree-lined avenues serve as an example of what Mumbai can be if its development is planned around trees and natural areas.

Jashvitha Dhagey is a multimedia journalist and researcher. She developed a deep interest in the way cities function, watching Mumbai at work. She holds a post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media from Sophia Polytechnic. She loves to watch and chronicle the multiple interactions between people, between people and power, and society and media.

Cover Photo: Jashvitha Dhagey

There is 1 comment

What a lovely piece indeed. Moved me to make a trip there this weekend. Written with love and insight… if only your voice is heeded. Bravo!