Subaidah Khatoon, a homemaker in Thokar Number 7, Shaheen Bagh, organises her day around meal preparation for her family of five, as most women do. An early riser, the 50-year-old cooks three or four full meals for her husband, Zakir, and their four children. These days, her nephew is living with them, so there’s marginally more food to make. “It’s a work of patience,” she says. It is also a challenge in these days of high food inflation for almost all women in this area of New Delhi, India’s national capital. A challenge multiplied several times when women’s routine work is placed in the context of unbearable heat waves and frightening floods.

As vegetable prices catapulted to new heights in recent weeks, Khatoon continued to cook basic dal and rice but in lesser quantities. When the prices of tomatoes shot through the roof, she planned curries without them. She loves to make a mean biryani but has to check herself because of the high cost it would incur. Khatoon is not fond of restaurant food though her son gets it once or twice a week; her younger daughters often desire a soft drink. Women like Khatoon are responsible for ensuring that their families are well-fed with nutritious food, sometimes even compromising on their own intake and health.

Shaheen Bagh, a middle-class predominantly Muslim area in south east of the capital, sprang to national and international consciousness in the winter of 2019 and early 2020 as women occupied the highway running through it to protest the draconian Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens (CAA-NRC). The chaalis futa road near the ground zero of the protest was known for its delectable street food even earlier. The Shaheen Bagh protest was punctuated by fresh food and tea served to women protesters and visitors. There is no dearth of variety – from Mughlai to Asian and everything in between. Biryani, the pan-Indian dish, was used as a communal slur during the protest by the Hindutva right-wing. Notwithstanding that, the post-protest Shaheen Bagh could be called Delhi’s latest culinary hub.

Photo: Creative Commons

Yet, the women who live in Shaheen Bagh and saw its value rise as a food hub[1] have different tales to tell about the food at home. Like Khatoon, women from low-income families here especially have been concerned about how their food choices and patterns have been limited by their families’ finances, health status and the infrastructure in the area. Women’s health and responsibilities are being affected by the fluctuating food availability in financially challenged households. All this is compounded by frequent heat waves and floods – outcomes related to Climate Change.

As temperatures soared in Delhi bringing in unprecedented heat waves this summer followed by frightening floods, the availability and quality of food as well as its access by women took a hit. The climate crisis also damaged local infrastructure and markets where women shopped for food. Rain water entered their homes and wrecked the stored food, many women live in tiny houses without proper storage facilities. Add to this the continuously rising food prices and the lack of clean drinking water in parts of Shaheen Bagh. Thousands of women like Khatoon then depend on nutritionally compromised food sourced from Yamuna floodplains’ toxic water[2] or unhygienic, non-nutritive food from restaurants, and water exorbitantly priced at Rs. 25 per can[3].

The intersection of food security, gender and Climate Change may still be a growing area for evidence-based research work but there is no doubt that the impact of Climate Change reflected in extreme weather events leaves its footprint on women’s lives, especially food. International studies and policy papers too have not substantively focused on urban environment as a factor in gender and security including food security. The interlinkages of Climate Change and women’s security were only formally recognised through the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda in 2015, according to this paper.[4]

Urban environment as a factor

For the women living in Shaheen Bagh, developments since the protest have taken on a bittersweet quality. Once barely acknowledged in the city’s urban imagination, the area now attracts more visitors than earlier[5] and has fended off a demolition threat.[6] Their challenges about food have remained the same – or worsened.

The demographic here comprises migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and Muslims displaced in communal riots from the 1980s. A 2022 study conducted by scholar Sajida Anjum shows that 43.4 percent of Muslims are self-employed in Delhi, while 17.71 percent are casual workers[7] Shaheen Bagh would show as much if not higher, and the conditions of self-employment are not significantly better than that of casual work.

Mostly described as a mixed-class area, Shaheen Bagh has sections with dismal living conditions. Urban environment such as is found in Shaheen Bagh plays a role too at the intersection of gender and Climate Change. Residents of such compromised urban environments struggle through severe inequalities to start with; of them, women and children suffer greater inequalities owing to their gender and age. These inequalities are further exacerbated by climate events such as heat waves and floods during which their access to food and water becomes compromised.

This was stated in no uncertain terms by the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) in 2015. “Climate Change threatens to reverse the progress made so far in the fight against hunger and malnutrition…it augments and intensifies risks to food security for the most vulnerable countries and populations,” it pointed out, adding that “food insecurity and breakdown of food systems” was a Climate Change-induced risk which would also “have broader impacts through effects on trade flows, food markets, and price stability and could introduce new risks for human health.”[8]

Photo: Samiya Khan

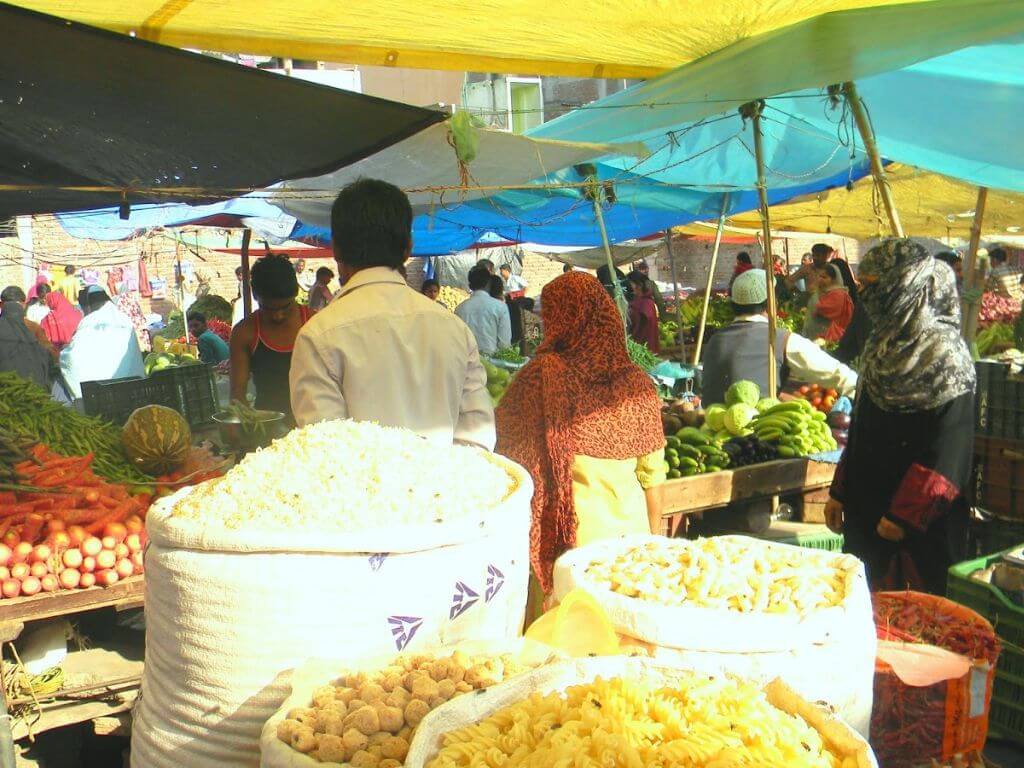

The mandis and women

The Climate Change-induced risk has been visible in the local mandi or market which is the backbone of food trade and sale, therefore availability. The High Tension Road Mandi is a major source of fruits and vegetables for the residents of Shaheen Bagh but it does not mean all women there can access the food. As Suvrata Chowdhary elucidates in her study ‘The Local Weekly Markets of Delhi: Operating in the Formal Space and Informal Economy,’ social networking is deeply ingrained in the character of the weekly market, not just in what is being sold and to whom but how it brings people together.

Personal food systems are intertwined with the economic systems of the mandis, making the presence of weekly markets crucial to people’s functioning. Since these markets have their own rhythms, climate crises and global health pandemics like COVID-19 wreck the livelihoods of those running it as well as those depending on it. “There’s no question of how much impact. Some shopkeepers went back to their homes, but many had to stay because this is their only way to earn,” Mohammed Irfan, 28, a spices vendor at Shaheen Bagh told me.

The pandemic disrupted the Mandi here, and therefore the access of residents to food, but the reportage focused on this or on the impact of Climate Change has been few and far between. Besides, the area falls in the low-lying part of the Yamuna River, whose water rose exponentially in July 2023 [9] disrupting the transportation and storage of fruits and vegetables. A large quantity of vegetables is brought from Okhla Sabzi Mandi and Azadpur Mandi in the north west of Delhi, with specific transport arrangements which suffer during heavy rain and floods.

“We are keeping four-day old produce here,” Moin, 42, said. Shopkeepers like him cannot afford to stock fresh produce if it has to be carried a long way. Humidity creates challenges in stocking fruits, vegetables and milk. Bilal, a dairy vendor at Kisan Doodh Dairy, said, “The milk is picked up at 1am from Garh, Uttar Pradesh, and reaches Shaheen Bagh at about 6am.” This has compounded the frequent rise in milk prices in Delhi[10] The cost of keeping milk and milk products cold is high. Climate vagaries mean the cost of spoiled perishables is borne by dealers who then minimise quantities.

The impact of this is borne by women whose access to food itself is compromised. This was affirmed by the International Institute for Environment and Development in its paper [11] where it stated that Climate Change affected not only food production but also its storage, distribution and eventually consumption, especially by low-income earners who are “net buyers of food”. Besides this, vegetables and other food items at the Mandi are largely hybrid varieties which can be a health risk for women as synthetic fertiliser-based food items are not marked; food grown in the Yamuna floodplains tends to be toxic due to presence of heavy metals.[12]

To cite the FAO, all four of its parameters of food security – availability, access, utilisation and stability – have been found wanting on a smaller or greater degree in Shaheen Bagh.

Food and women’s health

The irregular availability of food or lack of access to buy the food impacts women’s health. Food inflation and difficulties in access has meant a large section now heads to fast-food carts which, though affordable and convenient, can hardly replace nourishing food that pregnant women or older women need.

World Food Programme’s Assistant Executive Director, Valerie Guarnieri, says women are the bedrock of food security and yet are hardest hit by climate shocks and food insecurity. “A sustainable future is only possible when women and girls have what they need to adapt to the changing climate.”[13]

The link between food security – or the lack of it – in times of Climate Change and women’s health needs to be strongly made. Madhu Nagla, former professor of Sociology at MD University, Rohtak, explained that food choices have a class gradient; for example, well-to-do families use baking as an alternative to deep frying but this calls for more gadgets and resources in kitchens. Deep-fried snacks are part of daily dietary habits among both men and women, complemented with ubiquitous tea, for people without the resources for baking gadgets or disposable money for healthier options which tend to be expensive.

The cumulative and long-term impact of such choices is harsher on women who tend to be more calorie deficient than men and, therefore, at a higher risk for ailments and lifestyle diseases such as diabetes.

Healthcare facilities

The 2011 Dietary Guidelines published by the National Institute of Nutrition offers comprehensive recommendations for women, especially those who are pregnant and/or breastfeeding. Pulses and cereals are particularly emphasised, as well as foods with folic acid, calcium, iodine and vitamin A.[14] Despite this, the low nutritional content of the most accessible foods, that too at a time of rising inflation, places women and children in a particularly vulnerable health position.

The MS Swaminathan Research Foundation’s report [15] on the ‘State of Food Insecurity in Urban India’ stated several determinants for nutritional outcomes in cities: The level and type of consumption basket, access to safe drinking water, health services and environmental hygiene. Since the 1990s, these factors have made malnutrition a problem among women from poorer families in Shaheen Bagh.

To compound the challenges for women, there are only two major mohalla clinics at Shaheen Bagh, Cribs Hospital and Al-Shifa Hospital, as well as a bunch of private clinics and Unani medical centres set up by doctors in the locality. The Institute of Policy Studies and Advocacy’s 2022 report tells us of higher maternal mortality rates as well as malnourishment amongst children in Muslim-dominant areas of which Shaheen Bagh is no exception.[16]

Kitchen practices

Cultural factors play an important role in dietary practices. Since meat is part of the food practices among the majority of residents of Shaheen Bagh, the area’s carbon footprint may worry some but it is important to recognise that people who worry about food inflation can hardly bear the burden of thinking about carbon footprints.

Afifa Jabeen, 23, spoke of how she reused the oil from deep frying in her curries. “I make samosas for the evening snack,” she said, explaining the use of the oil later. A change means greater effort and more expenses. Dietary guidelines suggest that repeatedly heating oils can produce peroxides and free radicals which can cause oxidative damage to cells, accelerating coronary heart diseases and other lifestyle disorders.[17] But many women in Shaheen Bagh have to weigh this against the rising price of cooking oils. The health outcomes of food practices are compounded by the practice of gender norms such as women eating last or sparingly – prioritising others, especially men.

Photo: Samiya Khan

Shaheen Bagh lessons

When considering Climate Change impact, it is valuable to consider not just specific weather events but infrastructures and informal mechanisms like the ones in Shaheen Bagh to see what is at stake regarding food for a large number of people. The locality serves as an example of a self-regulated neighbourhood which operates flexibly but not disorganised, where people and needs are closely intertwined. One blip in the supply, and financially disadvantaged families end up with compromised food. Initiatives by the Aam Aadmi Party government like Smart Urban Farming, the initiative which aims to engage citizens in sustainable urban farming, is not feasible in Shaheen Bagh. The housing density and lack of sunlight would make it difficult for residents except those who have terraces in their homes.

Food needs ultimately depend on prevalent diets and food customs in a region. In the months of Ramzan for instance, large quantities of food are shared across Shaheen Bagh and other sub-localities of Jamia Nagar. Women are drivers of such food exchanges and are supported by their families when it comes to transportation, but festive occasions are the exceptions when people spend beyond their budget, splurge on making home-cooked delicacies or on street snacks.

The exception only emphasises the rule or the regular which is that women here, as elsewhere, trim and adjust their food practices and buying strategies all year round. Gender and food in times of Climate Change is an issue that needs deeper engagement from governments, policy makers and academia.

Samiya Khan, a writer based in New Delhi, focuses her work on the spatial dynamics of the city’s Muslim enclaves, at the intersection of community, social practice and informal economy. She is a graduate in English literature from Lady Shri Ram College for Women and holds a post-graduate degree in creative writing from Ambedkar University, New Delhi.

Cover photo: Juanita Kakoty