Anything that can go wrong will go wrong is a popular adage. It came true in a series of climate change-induced crises this monsoon in the western Himalayan region of India. Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, and Punjab were at the receiving end of back-to-back extreme weather events – cloudbursts, flash floods, landslides, broken bridges and highways, inundated farmlands, entire villages cut-off, and the dead buried under debris several feet high. It’s almost an apocalypse.

A recap is in order. On August 14, a cloudburst led to massive flash floods in Chashoti village in Chenab valley of Jammu division that killed at least 70 people[1] and left several missing[2]. Chashoti falls on the route of the famous Machail Yatra but it was suspended. Two days later, at least seven people died due to cloudbursts and landslides in Kathua district[3] of Jammu. This was followed by another cloudburst in Doda district[4] on August 26 that killed four people and led to heavy destruction. The same day, a landslide[5] triggered by heavy rainfall killed at least 34 people and injured pilgrims en route to Vaishno Devi, which was also suspended. Four days later, cloudbursts and landslides killed 12 more people in Ramban and Reasi[6] districts of J&K. There seemed no respite.

The Tawi river[7], which flows through the city of Jammu, swelled and caused havoc. Several localities struggled through waist-deep water as the flood ravaged homes and the standing kharif crops. The government claimed, according to news reports[8], that over 13,500 houses were damaged, around 150 people[9] killed and 178 injured in the ravages while 49,000 power distribution transformers were hit, more than 2,000 water supply works damaged, and crops on over 1,300 hectares of land destroyed. But this may just be a tip of the iceberg given that remote areas do not even have communication facilities.

The situation was no different in Himachal Pradesh. A series of cloudbursts and flash floods, similar to those in July 2023, in the districts of Kinnaur[10], Kullu, Shimla, Chamoli[11], and Lahaul-Spiti[12] caused widespread damage and havoc. Mandi[13] district faced the maximum brunt. At least 14 hydroelectric projects[14] were damaged, some of them affected multiple times over the decade. Environmentalists questioned if hydropower projects increased the incidence of natural disasters, such as cloudbursts, as reported in Down To Earth[15].

The Supreme Court’s statement “Himachal may vanish off the map if ecological damage continues”[16] brought the nation’s attention to the devastation in the region. By all accounts, climate change impacts are set to worsen or intensify, bringing more damage economically and ecologically. But it may be an easy scapegoat given that there has been reckless and rash construction along the ecologically-fragile Himalayan region.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Look beyond climate change

It is widely known that in the climate change era, a warming planet means bursts of extremely high rainfall; there can be 7 percent more moisture[17] for every one degree Celsius rise in atmospheric temperature. The disasters and devastation, therefore, cannot be termed only ‘natural’. The impact was intensified by the inherently faulty development model that has been unquestioningly adopted – and pushed – in the region.

This ecologically-blind build-more model means four-lane highways, tunnels, cable ropeways, multi-storey buildings, hotels, tourism, pilgrimages promoted with no thought to the carrying capacity of the region’s environment. The Himalayas are young, tectonically active, and fragile. Deforestation, slope de-stabilisation, tunnelling, dams, highways, glacial retreat; unregulated construction made it more vulnerable to climate risks.

J&K witnessed widespread land subsidence with massive ground cracks appearing in Tangar village, Ramban district, across Kalaban in Poonch, Sarh and Jamslan in Reasi, and several hamlets in Jammu and Rajouri. In all, nearly 3,000 villagers were displaced. They said their house walls collapsed, agricultural fields sank, and natural water streams vanished underground. This is not surprising. J&K’s unique topography of steep slopes and deep gorges makes it prone to flash floods. It is a seismic “ticking bomb”. Kashmir Valley, Doda, Ramban, and Kishtwar fall in Seismic Zone V (highest risk) while most of the region is in Zone IV. In such an eco-fragile landscape, forests have been cleared[18] for projects and riverbeds encroached upon to build tourist resorts. Predictably, in the recent floods, several of these collapsed.

The ‘Gurgaon-model’ of development, as I call it, is simply not applicable to the Himalayan region. Why is it so difficult for authorities to understand this? In fact, this build-more model is not working even in swanky Gurugram[19] which comes to a standstill with a few millimetres of rain in a couple of hours.

More than cloudbursts

The Indian Himalayan region covers 12 states with a population of over 50 million who depend on its natural wealth and ecosystems. Climate change has already disrupted seasons. The impact of these changes has wreaked havoc in the past few years. The Himalayan region, highly sensitive to climate change, has shown significant impacts on the environment and human communities, noted a recent paper[20]. Scientists and policymakers recognise the region as one of the world’s most vulnerable ecosystems experiencing unprecedented changes in its cryosphere, hydrology, and biodiversity.

Large-scale construction, using land without a nod to ecology, is akin to hara-kiri here. Blaming cloudbursts conveniently takes away the responsibility from planning authorities and government agencies.

There has been an increase in cloudburst events. Although heavily used in the news media, the term ‘cloudburst’ does not merely imply heavy rainfall. The India Meteorological Department defines it as 100 millimetres or more rainfall in an hour over a small area of 20-30 square kilometres. Without weather monitoring stations in remote Himalayan locations, it is difficult to ascertain the amount of rainfall but the frequency and intensity are people’s lived experiences.

One reason is an interaction between two powerful weather systems — southwest monsoon and western disturbances. A western disturbance[21] is an extratropical storm originating in the Mediterranean region and carrying moisture from the Mediterranean and Caspian seas east to bring precipitation to north India. Western disturbances have seen a reduction[22] in the winter season and are on the rise[23] in the summer and monsoon season in the past few years.

This monsoon alone saw at least 17 western disturbances across India, far more than the normal four. The increased interactions between India’s monsoon system and the western disturbances caused a series of cloudbursts in the western Himalayan region. The catastrophic Uttarakhand floods in 2013 and floods across north India in 2023 were also due to this interaction.

Cloudbursts are routinely blamed but it begs the questions: What are governments and local agencies doing to protect human lives, why are early warning systems and climate-resilient infrastructure absent, why have repeated warnings by climate scientists about extreme rainfall fallen on deaf ears? To continue ‘development’ as if all this did not matter is almost criminal.

Ignoring climate signals about rivers

Climate science findings and projections should push governments at the Centre and in states to focus on building climate resilience in the Himalayan communities. Instead, with the wrong development model, they are throwing these communities under the bus. There’s a price to pay for disregarding ecology and people are paying it.

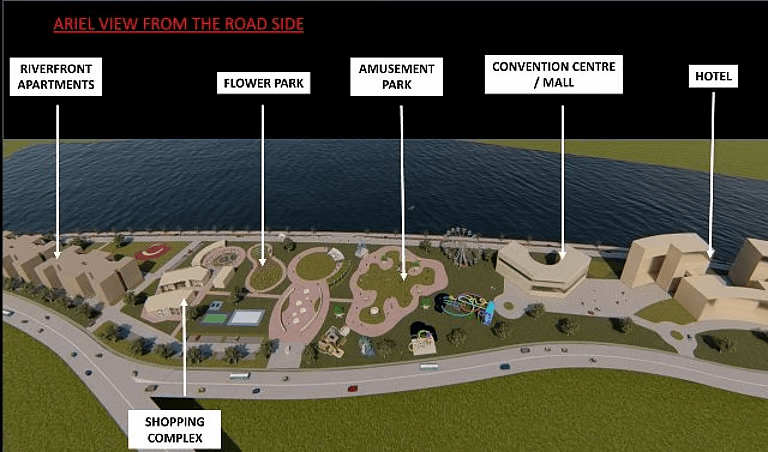

The Tawi Riverfront Development Project in Jammu city was predictably meant to be a picture postcard. The thematic image below shows its claims. Along the banks of the Tawi are manicured gardens, multi-storey apartments, an amusement park, a convention centre-cum-mall, a hotel, shopping complex, a flower park, and a giant Ferris Wheel like the London Eye.

Photo credits: Nidhi Jamwal

Divided into two phases, the Tawi project’s[24] first phase concretised parts of the riverbank between Bhagwati Nagar Barrage to Bikram Chowk Bridge. A total of 2.7 kilometres of the embankment is being developed with four promenades of varying widths. About 23 hectares of land was ‘reclaimed’ for this. In the August floods, the Tawi claimed it back.

This raises serious questions about the model of riverfront ‘development’ itself which is an assault on the natural edges of rivers. Instead of making space for rivers to swell to carry rainwater, riverfront projects concertise riverbanks and constrict them. Despite people’s protests and lessons from nature, one city after another across India has rushed into the riverfront development craze. This essentially channelises the flow of a river, concrete embankments and channel modifications destroy river habitats and biodiversity, deep concrete walls sever the natural connection between rivers and their aquifers blocking both groundwater recharge and natural drainage channels.

All this harms long-term water security, river health, and its ability to carry floodwater. Is it any surprise then that heavy rainfall events worsened riverine flooding? This was witnessed during the recent floods in Jammu. Besides, rivers self-purify as they flow which protects their water quality and ecological health. Riverfronts degenerate the water quality, as has been documented in research studies, due to water stagnation between artificial barriers.

The study, Impact of Riverfront Development on Self-Purification Capacity: A Case Study of Devika and Tawi River,[25] in 2024, focused on this aspect in the two rivers in Jammu — Tawi and Devika — where riverfront projects have been planned. It found that the sample from the undisturbed section of the Devika River (upstream of riverfront project) had higher dissolved oxygen (DO) value than the samples collected near the riverfront development with a more flattened slope; also, the biological oxygen demand (BOD) from the undisturbed section was lower than that near the riverfront development.

The study concluded that “the steeper the slope, the better the water quality parameters”. Importantly, it pointed out that the river has lower self-purification capacity due to “insufficient slope of the river which once the riverfront is completed is expected to be worsened due to the backwater curve”. What still explains the riverfront project?

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Deforestation and more

It’s not just the rivers, trees and forests are cleared to be made ‘developable land’. A staggering 5.84 lakh trees[26] were cut in J&K between 2020 and 2025, as part of an ‘anti-encroachment’ drive along the Jhelum river in Kashmir. Officials claimed that the trees ‘encroached’ on riverbanks and canals resulting in huge damage during earlier floods. But environmentalists warn that such large-scale deforestation in an ecologically-sensitive region could have devastating long-term consequences.

Trees, especially along riverbanks, play a crucial role in stabilising embankments, preventing soil erosion, and regulating temperatures through shade and evapotranspiration. Local communities blame the “land mafia” that has encroached on rivulets, streams, and “gair mumkin khad” (water courses) in the hill states. But some encroachments have official approval such as the AIIMS Jammu (also known as AIIMS Vijaypur) project in Samba district. It has come up on a khad [27](ravine).

The recent floods in Jammu badly damaged the bridge on Devika River which leads to the AIIMS Vijaypur buildings. Deputy chief minister Surinder Choudhary slammed[28] the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) for poor quality of roads and bridges including “substandard construction[29] by the implementing agencies.” Local politicians acknowledged[30], however, that illegal mining of sand and stones damaged bridges, including Sahar Khad bridge in Kathua and Devika bridge at Vijaypur, leading to their collapse.

Instead of building climate-resilient infrastructure, governments are promoting tourism by investing in infrastructure projects to make travel faster for lakhs of tourists and pilgrims. Dozens of centuries-old deodar and pine trees were recently axed at the construction site of the Bijli Mahadev ropeway[31] in Kullu district of Himachal. Once completed, it will carry pilgrims and tourists from Pirdi base station to the 2,460-metre-high Bijli Mahadev temple in a 2.4-kilometre cable car ride, reducing travel time from three hours to 10 minutes.

The ropeway, touted as a dream project of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is being developed by National Highways Logistics Management Limited (NHLML) at a cost of Rs 284 crore. The company deposited Rs 5 crore[32] for compensatory afforestation but locals argue that money cannot replace ancient trees. Hearing a petition filed by Nachiketa Sharma, a resident of Kullu, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) issued notices to the Centre and the Himachal Pradesh government over this project. He alleges that it was granted clearance without proper environmental appraisal, carrying capacity studies, or slope stability assessments. Similarly, the proposed gondola ropeway in Pahalgam, which threatens around 800 conifer trees, has also faced opposition from the J&K Forest Department.

Nature-based solutions

If land in the ecologically-fragile region cannot be taken for development, what is the way out? It would be wise to remember that the Himalayas are not shopping malls of Gurugram that need high footfalls to make business sense. These eco-fragile regions need protection and controlled growth, and promotion of nature-based economies. Rather than building on nature, there is an urgent need to build with nature.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

As climate-induced rainfall patterns change and extreme weather events increase, nature-based solutions would be to rejuvenate and protect wetlands. A large number of these water bodies are encroached upon. Wular lake in Bandipora district of J&K, considered one of Asia’s largest freshwater[33] lakes, has shrunk by 45 percent[34] from 157.74 square kilometres in 1911 to 86.71 sq km in 2007. According to a 2022 report by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), BOD levels[35] in parts of the lake exceed the safe threshold of 3 milligram per litre (mg/L).

In the 1992 floods in J&K, water from the Jhelum River gushed into Wular, depositing vast amounts of silt across the lakebed, choking aquatic plants and damaging its delicate ecology. The Wular Conservation and Management Authority’s Lake revival plan in 2020 helped desilt it Sustained efforts by local communities and grassroots organisations have started to bear fruit as lotus flowers[36] bloomed once again after nearly three decades. “Wular Lake is on the path of recovery. If it hadn’t been for this lake, the entire Kashmir region would have faced even worse floods during this year’s monsoon,” said renowned Kashmiri filmmaker, Jalal Jeelani. His documentary on Wular lake, Saving the Saviour[37], was telecast on the National Geographic channel.

Equally importantly, local people should be involved in the regeneration and protection of pasturelands and grazing lands. This provides livelihood opportunities to nomadic communities like Gujjars and Bakarwals, and helps slope stabilisation. It is worthwhile to remember that the tourists and pilgrims will pass by, the politicians will enjoy power and fame, but it is the local hill communities that will face the impact of reckless construction that is inexplicably unmindful of the region’s ecology.

Nidhi Jamwal is an independent journalist who reports on environment, climate, and rural issues. An award-winning journalist with more than 25 years of experience, she is the recipient of ‘UNFPA@50 Special Laadli Award 2024’ for consistent engagement on feminising climate solutions.

Cover photo: Tawi river flowing through Jammu.

Credit: Timothy A. Gonsalves/ Wikimedia Commons