Deep in the dead of the night at the Anand Vihar Inter State Bus Terminal in Delhi, the sight and sound of Bus 0543A trundling in gives hope and confidence to many waiting commuters. This bus will take them across the city through the night’s darkness and silence, as the city sleeps, to their work or home. It is the set of wheels that keeps the city’s early morning rhythm rolling, bringing the regulars to their workplaces by 3am or 4am. It is also the bus that new migrants, wide-eyed with trepidation and fear, take to their new addresses. Bus 0543A has the same ticket fee during the day and night, with no additional night charges, and free tickets for women passengers.

Delhi might not be the same city that it is if not for this bus route run by the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC) since 2015. One of the longest routes of the DTC, it connects Anand Vihar to Kapashera border, 40 kilometres apart, with running time of 90 to 100 mins during the night and more than 120 mins during the day. There are 31 bus routes plying during night such as Old Delhi to Mehrauli but the significance of Bus 0543A is that it touches transport terminals, major hospitals, railway station and other key destinations – and thereby makes the city accessible. It runs one round from Anand Vihar to Kashmere gate and one round for Kapashera border each night. The number of trips for each route depends on the distance it covers.

The Bus 0543A ensures accessible connection in the darkest hours for those who cannot afford private cars or even two-wheelers – the epitome of what public transport ought to be. Those who take the route form a community of sorts, faces that are familiar to one another, drivers who know where commuters are and take diversions to board them, and so on. This story of DTC Bus 0543A has been captured in Shab-Parak (Night Fliers), a 8:29 minute film which won the Silver Bioscope at the Nagari 2024 short film competition of the esteemed Charles Correa Foundation.

The jury citation reads: “Shab-Parak’s power lies in its cinema verite form. It constructs a compelling narrative using real people’s voices and beautiful images shot live on location; instead of relying on an external storyteller’s voice. The film draws attention to a major issue, accessing the city at night, that relates not only to Delhi where this story is set, but to all urban centres. It gives us a glimpse into one of the many unnoticed worlds that exist within a city, and shows how strangers form a community through the simple act of travelling together on a late night bus.”

The film can be viewed here

Focus of the film

Shab-Parak, made by Sabika Syed and Nikhil Mehrotra, is a quiet film in that it allows the story of Bus 0543A to shine through. It is about the convenience in a city wide and far-flung, a city that does not always keep its poor at the heart of policy decisions. The film offers a glimpse into this other side of life in Delhi that’s so rarely discussed, let alone celebrated, because the people who populate it are quiet foot soldiers. In capturing the route, the people who use it, and their interactions with their city, Shab-Parak shows how this night bus service is literally the lifeline of India’s national capital.

In following the bus journey, Shab-Parak peels off the layers of a transit system that’s less known even to Delhiites. Its network of more than 25 stops keeps the city knit through the night. For the working class of the city, it is an essential lifeline allowing them a degree of comfort and safety as the quiet sleeping city turns intimidating. The film tells stories of the commuters and driver Shabbir Khan, the unspoken relationship between them, the smiles and dismay.

Syed and Mehrotra wanted to show a system that was central to a city within the theme of ‘mobility in urban India’ given for the Nagari competition. They spent a month researching the routes that night buses – 31 in all – take before focusing on this one. They found Bus 0543A most apt for its length and connectivity. It was the longest of night routes stretching from the border of Uttar Pradesh to that of Haryana, it was the most crowded, and its characters were more than interesting including the enthusiastic driver Shabbir Khan.

“No other transit system in any metropolitan city, especially the national capital, will ever cater to the kind of population that a public bus system does. So, we were able to narrow it down there. It was also something that had never been explored,” they said to Question of Cities. The bus route became their ‘home’ for the nights they were shooting. “Delhi is a big scary monster even for people who have lived here for many years,” said Syed explaining why migrants at Anand Vihar ISBT find it intimidating.

Syed and Mehrotra also anchored their story to the city by showing that the people on it are the ones who wake up Delhi and get it going in the morning – drivers, cleaners, cooks, factory workers, canteen workers, airport workers, staff clocking in by 4 or 5am, retailers and dealers who must go to the mandi, and so on. The foot soldiers of the city.

Not surprisingly, a large number of commuters on night buses are migrants to Delhi who trust it more than rickshaws or tempos; it is more affordable too, as commuters speak in the film. “The reality is that a lot of people who migrate to big cities don’t have money in their pockets. We met some with barely Rs 30-40. They can’t afford any other mode of transport. This costs them Rs 15, takes them across 20-25 kilometers, and drops them at their destination. It doesn’t get cheaper than that,” said Syed.

Migrants feel safe too as Dharmendra Yadav says on the screen: “Yahaan se auto wala bithake le gaya tha road se, fir pul pe chadhke wahaan uske bande khade the. Bandhke rakh diya, paise cheen liye aur chaku maarke boldiya khatam kar denge. Wo dobara aya nahi yahaan par. Isiliye auto se kam jaate hain, bus se zyada chalte hainnn.” (The auto driver had picked him up. Somewhere on the way, the auto driver’s men were waiting. They tied the passenger, stole everything, stabbed, and threatened to kill him. This is why I travel by bus, and rarely by auto).

The nocturnal community

Driver Shabbir is like the sutradhar of this night bus story. He understands his commuters, they are like a community to him. He says, “Log safar me aate hain, jaise koi UP se aa raha hain, Haryana se, Rajasthan se aur unka kayi kayi ghante ka safar train mei ya bus mei guzra hain. Ab jahaan tak unhe jana hain vahan tak to bus hain. Par vahan jane ke lie vo hamari ratri sewa ka sahara lete hain.” (People in transit come from as far as Haryana, UP, Rajasthan, travelling for hours in trains and buses. But to reach their destination, they take the night bus service).

Like all bus routes, Bus 0543A also has a fixed path but Shabbirji understands his community and makes the diversions he thinks are appropriate, dropping off people a small distance away from the designated bus stop but close to their destination or turning into a bylane because he knows a woman boards it there. “Aur abhi ek ladki chadhegi yahaan se. Wo kisi factory me jaati hain, roti banane ka kaam karti hain.” (A young woman boards from here. She works at a factory, making rotis there), says the driver in the film. There are usually 2-3 women on this route.

Every hour of the night unfolds differently and brings varying commuters to his bus. At 11pm, work shifts end. At midnight, people travelling long-distance by early morning trains make their way to railway stations. By 3am and 4am, the early morning worker community starts its commute. “Ye jo Dilli ka bus system hain na wo pure Dilli ko samet leta hain. Ye saare veins hain jo sabko connect kar raha hain. Saare nase hain jo usko samet raha hain.” (This bus system of Delhi encompasses the whole city. These are all the veins which are connecting everything else. Veins forming the city), says the driver explaining the centrality of the bus he commands. Many drivers and conductors have been moved to the contract system but they, unlike private bus contractors, are still accountable to the DTC.

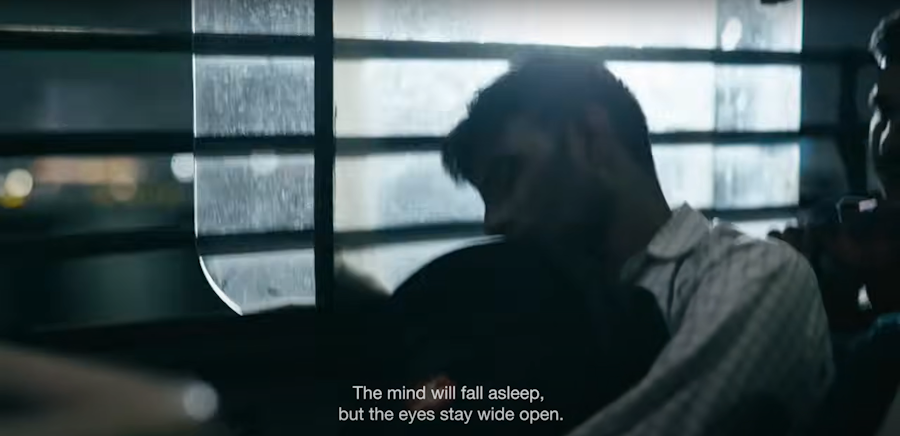

How does he keep awake when on this shift? “Dimaag so jaata hain. Ankh khuli rahegi. Thakaan bhi hotti hain, neend ka bhi takaza hota hai. Aur fir umar ka bhi takaza hain” (The mind falls asleep. Eyes remain open. It gets tiring, there is an urge to sleep as well. I am getting old too), he winces. Shab-Parak, or Night Flier, could well just be driver Shabbir on Bus 0543A. Or the route. Or even the city itself.

Capturing the change

Shab-Parak subtly but firmly captures the change that is wrought on Delhi’s transport systems. “The ISBT changed in front of our eyes. When we were at Anand Vihar ISBT they were reconstructing it by evicting all the people who were selling chai and food, and bringing in private players inside the terminal. Now, the waiting commuters find it harder to make seating space or waiting space, let alone afford to eat there. As we watched, things moved from need-centric to profit-centric,” explained Mehrotra to Question of Cities.

The filmmakers said that during the shooting, Anand Vihar ISBT’s small shops had stools-tables where people could simply wait without making any purchase. These informal accessible public spaces quickly disappeared or were systematically removed. While the privatisation of the public transit system appears to improve infrastructure, it is reducing accessibility, focusing only on functionality. Metro stations and trains, for example, are strictly for transit and eating is prohibited. In fact, workers from certain professions are not allowed to carry tools, making Delhi’s famed metro useless for them. This makes urban spaces highly inequitable.

The reconstruction of Delhi with new metro stations, metro lines, and expressways particularly around areas like the ISBTs has created an urban landscape with ‘negative spaces’ or spaces to sit, pause, and wait till they resume the next leg of their journey. The ISBTs were just like railway stations; this is changing, raising questions about whether public space really holds people. This rigidity could deepen when the Delhi Master Plan 2040 is fully implemented, further alienating people from the very systems meant to serve them.

This is where a film like Shab-Parak remains a resolute reminder of what accessible and thoughtful public transport can be.

Nikeita Saraf, a Thane-based architect and urban practitioner, works as illustrator and writer with Question of Cities. Through her academic years at School of Environment and Architecture, and later as Urban Fellow at the Indian Institute of Human Settlements, she tried to explore, in various forms, the web of relationships which create space and form the essence of storytelling. Her interests in storytelling and narrative mapping stem from how people map their worlds and she explores this through her everyday practice of illustrating anqd archiving.

All photos are stills from the short film Shab-Parak | The Night-Fliers.